In a world first at the Macquarie University Fish Lab, researchers have discovered that Port Jackson sharks like to spend time with other sharks of the same sex and size in relationships that endure for years. In other words, females have friendships with other females, males with males, and young sharks don’t mix with the grown-ups.

“A lot of it comes down to having similar likes and preferences,” explains Associate Professor Culum Brown of the Department of Biological Sciences. “You know that [human children] don’t like to hang out with the oldies because oldies are kind of boring and don’t do anything that children are very interested in, so it’s almost certainly similar in the animal world.”

Brown and his team used acoustic tagging and underwater receivers to record interactions between sharks, and then applied social network analysis to discover that far from random associations, the Port Jacksons were preferentially hanging out with particular individuals that were similar to themselves.

Such friendships are good for survival, says Brown, as groups of familiar individuals who can predict each other’s behaviour are better at foraging for food and staying safe from predators.

“When most people think of sharks they think of mindless killers that are loners,” says Brown. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

A very high fidelity

There are hundreds of thousands of Port Jackson sharks down the east coast of Australia from the NSW-Queensland border and around the southern coastline to Perth. In Jervis Bay in southern NSW, where the Fish Lab conducts its tagging, about 10,000 of them gather during the winter breeding season. Despite a “crazy” 1000-kilometre migration to Tasmania and back, they return each year to the exact same reefs to reproduce – a behaviour, discovered by Macquarie, that has never been reported in a shark species.

“Port Jacksons are very, very common, if not the most common shark in Australian waters, and until we started working on them six years ago we knew almost nothing about them,” says Brown.

“The thing that struck us was this really high fidelity to these breeding reefs and we thought if they’re doing that, then they must be hanging out with the same animals year after year, and they are very long lived – a Port Jackson shark doesn’t mature until it’s in its teens, and probably lives more than 50 years - and it appeared to us that all the conditions were right for pretty complex social interactions and it turns out that’s true.”

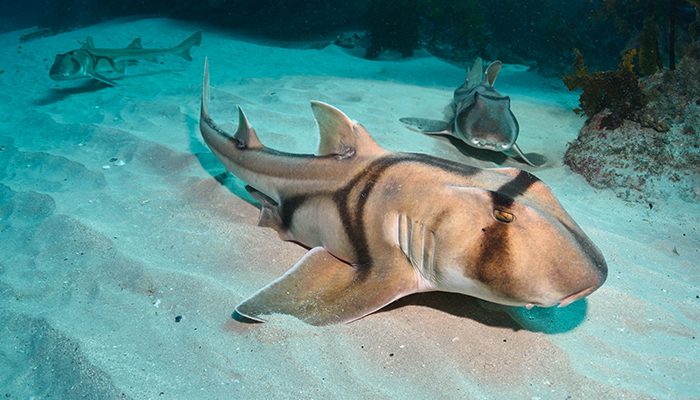

Also true: the distinctive-looking sharks with their pig-like snouts and forehead ridges are nothing to be scared of, says Brown. They are small – the females grow to a maximum 1.5 metres, males to 1.3m - and their teeth are for crushing, not tearing. In handling thousands of them over six years, Brown has been bitten only twice, and the worst of those was just “a bit of a hickey”.

“There are not so many people in the water in winter, but if you were you’d almost certainly see them - people send me pictures of their kids swimming with Port Jacksons all the time around Sydney. They’re harmless.”

Culum Brown emphasises the similarities between humans and animals.

Personality plus

An earlier Macquarie-led study, published last year, found that Port Jackson sharks have individual personalities. This was established by behavioural tests that exposed them to the uncertainty of a new environment and the stress of human handling and noted their level of boldness in the first test, and their recovery time in the second. Over repeated trials, researchers observed consistent and distinct responses in individual sharks.

Now, with those personality scores at hand, and with the continued recording of their underwater interactions, Brown says the next couple of years should produce enough data to determine if the sharks are associating based on personality.

Such a finding would further “humanise” an animal with a terrible reputation, and Brown would be happy with that.

“There are far more similarities than differences between animals,” he says. “Not long ago you would have been kicked out of class for trying to humanise an animal, but there’s really been a dramatic shift in attitudes among scientists in the past 10 years; in the past year or two it’s gone berserk.

“One of the things I try and do is impress upon people that animals are really deserving of our respect. I’m not saying they should get the vote but at the very least treat them well and minimise harm and think about the world from their perspective whenever you’re interacting with them.”

Discover more about the Macquarie University Behaviour, Ecology and Evolution of Fishes Laboratory