The location of the brightest cosmic explosion ever recorded was pinpointed at 2.4 billion light years from Earth by a team which included Macquarie University researcher Dr Tayyaba Zafar.

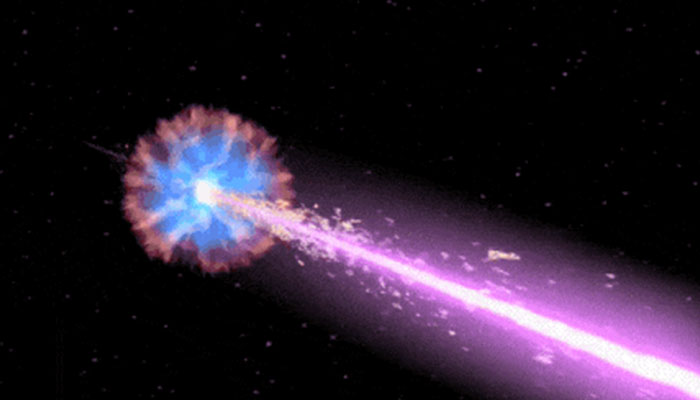

Brightest blast: This image shows the explosion from the death of a star, producing gamma-ray jets in narrow beams. If these beams point towards us, we see a gamma-ray burst (GRB). Image: NASA.

Her insights into how dust affects light as it journeys through space were invaluable in analysing the spectra that identified the exact location of the explosion, believed to be the dying display of a giant star many times larger than our Sun.

The blast, known as a gamma-ray burst (GRB), was first picked up by sensors on veteran spacecraft Voyager 1 last October, only arriving at Earth 19 hours later.

It was then detected by several gamma-ray space telescopes, such as NASA's Swift and Fermi and the European Space Agency’s INTEGRAL.

While this is the brightest gamma ray burst seen from Earth in the 55 years since the first gamma-ray satellites were put in orbit ... blasts of such intensity may occur every 1000 years or so.

But it wasn’t until spectroscopic data, collected by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), was analysed that scientists could finally locate the origin of the GRB in a previously unknown galaxy.

“Initial reports suggested that might even be coming from inside our own Milky Way galaxy,” says Dr Zafar, of Macquarie University’s Australian Astronomical Optics.

“But we were able to accurately measure the distance because we had the spectroscopic data, as well as infrared and optical, from ESO.”

Scientists believe the blast was so bright because of its relative proximity and because the beam of radiation was pointing in our direction.

But this GRB was also unusually long in duration. In general, GRBs can last from milliseconds to a few hours but this one, designated GRB221009A, was detectable for 10 hours.

There were other oddities about this blast – particularly the lack of any sign so far of a supernova, which could be expected with such a massive explosion.

“With something this large, you expect that it must be a star dying in an explosion at the end of its life,” says Dr Zafar. “We now think it must have collapsed immediately in on itself to become a black hole.”

Macquarie star: Dr Tayyaba Zafir, pictured, worked with scientists from 30 global research institutions to identify the location of the brightest cosmic explosion ever recorded.

While this is the brightest gamma ray burst seen from Earth in the 55 years since the first gamma-ray satellites were put in orbit, Dr Zafar’s team, led by Dr Daniele Bjørn Malesani of Radboud University in The Netherlands, believe blasts of this intensity may occur every 1000 years or so.

The paper identifying the location of the blast involved 42 scientists from 30 research institutions around the world. It has been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

A second paper by team led by Andrew Levan, of Radboud University, which also included Dr Zafar, observed the explosion with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) at longer wavelengths. Combining the ESO spectrum analysis with the JWST data allows for an in-depth investigation of the nature of this blast. It will be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“Working with such a huge, vibrant international collaboration was amazing,” says Dr Zafar.

“From the time of the initial blast, we were chasing data through ground imaging and spectroscopic facilities. We realised early on that we needed time with the JWST and Hubble Space Telescope (HST) to study the event in detail.”

Dr Zafar’s career in astronomy took off as a PhD student at Copenhagen University.

“I was always interested in the vastness of the heavens,” she says. “I was a physicist but it was my PhD in astronomy that gave me a breakthrough to opt for professional astronomy.”

She was a fellow at the European Southern Observatory where she worked with telescopes at the Paranal Observatory, in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, including the VLT.

“I moved to Australia to support the Australian Astronomical Telescope at what was then called, Australian Astronomical Observatory.

"That’s now the Australian Astronomical Optics (AAO), a new department at Macquarie University, where I work on astronomy and space international instrumentation projects.

“I am looking forward to observing more exciting events such as GRBs as we develop our facilities into the future.”

Astronomer Dr Tayyaba Zafar is a senior lecturer at Australian Astronomical Optics, Macquarie University, Faculty of Science and Engineering.