Why is it that complex projects which the community depends on - such as renovation of the iconic North Sydney Olympic Pool or the Sydney Metro extension to Bankstown - often take much longer than expected leading to major frustration and a big hit on the public purse?

Delay upon delay: the redevelopment of North Sydney pool, pictured above, is three years overdue with the current estimated opening late 2025.

While each project is affected by individual circumstances, researchers at Macquarie Business School have found there are some surprising reasons why project planners often make poor estimates of project timelines.

The good news is the authors say their study has uncovered some straightforward strategies which project managers can use to avoid delays.

Work on North Sydney Pool redevelopment, for example, began in March 2021, with the original deadline for completion estimated to be late 2022. A revised deadline of July 2024 was later announced, but thanks to ongoing design and construction disputes, as well as cost blow outs, the deadline for opening has now been pushed to the second half of 2025.

Macquarie Business School doctoral graduate Dr Matej Lorko, who spent five years as an IT project manager at major steel producer U.S Steel in Slovakia, saw projects constantly failing as part of that role - “even ones that seemed to be managed quite well”.

“I realised that there had to be something that the textbooks don’t cover,” Dr Lorko says, who leveraged his corporate experience in the research.

Collaborating with experimental economists Professor Maroš Servátka and Associate Professor Lyla Zhang - his doctoral supervisors - the trio came up with a series of economic experiments to test ideas about how to avoid project failure.

Incentives a key strategy

In their paper, published in MIT Sloan Management Review, the authors present managerial insights flowing from the experiments. Dr Lorko, Professor Servátka and Associate Professor Zhang warn project managers that too much focus on delivering projects on time can backfire and result in slower project delivery. They advise that incentive structures be designed to reward speed of delivery in addition to rewarding accuracy in estimating the time of delivery.

In the first experiment 93 participants were given a simple, repetitive maths task and, before doing it, were asked to estimate how long it would take. They were divided into three groups and the first two groups were given an “anchor” - a subtle hint as to how long the task could take - before they made their estimate.

Practice meets research: Study author Dr Matej Lorko. Image credit: David Ištok.

Before the first group gave their estimate of the duration of the task they were asked if they thought it would take more or less than three minutes.

The “anchor” for the second group was at the opposite extreme. Before giving their estimate they were asked if the task would take more or less than 20 minutes. The third group was not given any anchor before they estimated the task duration. Then the participants in all three groups did the task.

- Travellers willing to pay more for low-emission flights

- UniSuper boss Peter Chun on life-long learning and embracing AI: video interview

The participants went through the process three more times – each time making a new estimate and then repeating the task.

The interesting result was although all groups took the same time (on average) to complete the task, those who had been given a three-minute anchor continued to underestimate the time, even when they repeated the task three more times. Similarly, those given the 20-minute anchor continually overestimated the time.

Lesson one: start with a blank canvas

Professor Servátka said the lesson is when estimating project timelines, you should start with a blank canvas and not be influenced by expectations such as pressure to complete before Christmas or a CEO asking: “can we get it done in two months?”. Otherwise these “anchors” will lead to errors which are not easily corrected, despite the planner’s experience.

Experimental economist and co-author: Professor Maroš Servátka, pictured above.

The second experiment, which involved a new group of 130 participants being divided into three groups, tested what type of information is most useful to project managers to improve the accuracy of task duration estimates.

Each group was asked to estimate how long a project - a separate repetitive maths task designed to be harder than it looked - would take. One group based their estimates on a detailed description of the task. The second group was told how long such a task had taken other people, while the third (the control group) was given no information.

The result illustrated the difficulty in accurately estimating how long a task will take even when you know exactly what is involved.

Both groups which had prior information made more accurate estimates, on average, than the group which was told nothing. But there was a larger variance in the estimates made by the group that was given a detailed task description, with some participants largely overestimating the duration and other largely underestimating it, which is what project managers want to avoid.

The result illustrated the difficulty in accurately estimating how long a task will take even when you know exactly what is involved.

Associate Professor Zhang said it is important for project managers to reference similar past projects and generate more reliable estimates by taking note of how long it took other people to do similar tasks.

Contractors vs in-house teams

The third experiment stemmed from Dr Lorko's project management experience, he says, when he observed that teams from within a company were habitually late in completing tasks. In contrast, teams of contractors from outside the company were usually on time.

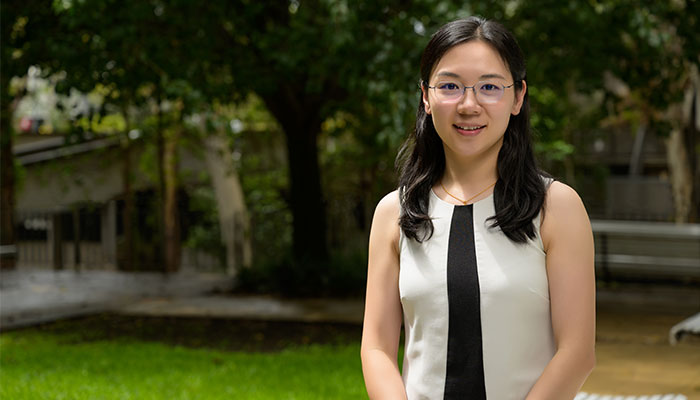

Experimental economist and co-author: Associate Professor Lyla Zhang, pictured above.

He hypothesized that contractors were inflating their time estimates, which allowed them to create a time buffer, and then slowing down their work to match the estimates, resulting in a hidden inefficiency.

To test this, 198 new participants were recruited and divided into three groups to perform a simple search task. One was incentivised to complete as fast as possible, which established a benchmark for how long it would take.

The second group was incentivised to estimate the task accurately. On average this group made significantly higher estimates than the benchmark. Then when people in the second group came to carry out the task they did as the researchers had hypothesised - they slowed down their work and finished close to their inflated time estimate.

In contrast the third group, which was incentivised for both speed and accuracy, completed the task faster than the second group and their time estimates were often very good.

The experiement confirms that a strong emphasis on avoiding overruns can be counterproductive - projects are seemingly completed on time, but resources are underutilized.

Maroš Servátka is a Professor Of Management and Economics in the Department of Economics, Director of the Macquarie Business School Experimental Economics Laboratory and Deputy Director of the MBA Program.

Lyla Zhang is an experimental economist and Associate Professor in the Department of Economics.