For decades there has been a nostalgia for the 1950s and ‘60s. For the milk-bar cowboys and peroxided, pony-tailed girls, for motorbikes, hotted-up cars, Little Richard, leather jackets.

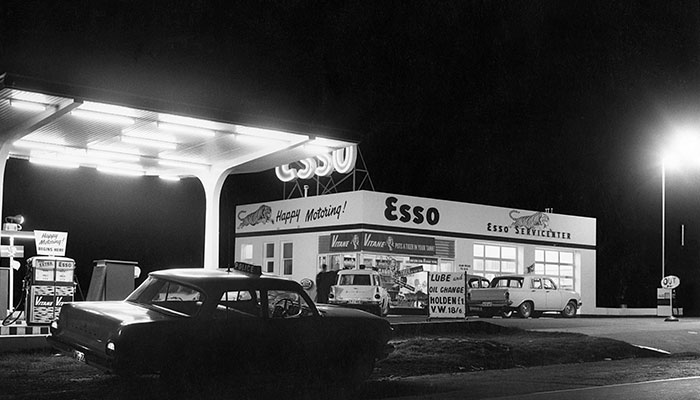

Crime scene: The Esso petrol station on the Hume Highway, Lansvale, 1964, where a fatal armed robbery took place. Image: Estate of the late B K Doyle.

But other than the slick quiffs of mug shots and the odd electric guitar turning up as recovered stolen goods, there is little evidence of the grand social upheaval of the times in the police archives.

Combing through police photo archives from the mid-century, while researching my latest book Suburban Noir, it’s remarkable how small-time and dead-end the crime mostly was.

Photographic evidence of stolen goods depicts socks, bookends, table lamps, transistor radios, trousers, berets and hats. People would steal washing machines, lounge suites, car parts, tyres, car radios, golf clubs. They took pharmaceuticals from the cupboard, bottles of soft drink, binoculars, make-up, fountain pens, ornaments. And, of course, those new-fangled TVs. Even rolls of linoleum and carpet, tools from the shed. Pretty much anything that could be sold at the pub.

It tells you a lot about people’s levels of consumption – unimaginably lower than now. The desire for nice things might have been keen but supply not so much.

Not surprisingly poison was a popular way to do away with those who’d done you wrong – rat poison, weedkiller, arsenic.

I spent several years researching and curating exhibitions (Crimes of Passion and City of Shadows: Inner City Crime and Mayhem, 1912-1948), that drew on tens of thousands of jumbled forensic negatives in storage at the Justice and Police Museum in Sydney.

But one of the most fascinating archives is that of my late uncle, Detective Brian Doyle, who was the Senior Assistant Commissioner of Police in NSW in the 1970s. He worked on two of the most famous cases: the kidnapping and murder of schoolboy Graeme Thorne, whose parents had won the lottery, and the case of the so-called Kingsgrove Slasher.

Among the mug shots and photos of homicide scenes and corpses are more cryptic crime scenes: a wardrobe stacked with bottles laid side by side, each tightly wrapped in newspaper; the remains of a blown-up fibro cottage; close-ups of blood-stained linoleum, a diagram of a hotel room.

Surveying the forensic material – the images, file entries, reports, testimony, sworn statements, newspaper articles, court reports – I was continually confronted by the grinding tawdriness, futility, the dead-end small-timeyness of everyday crime and mishap. It made urban life appear pinched, bitter and small.

Mid-century pictures: Author Professor Peter Doyle (pictured) combed through photographs, police reports, sworn statements and newspaper articles to put together his portrait of the Sydney crime scene in the 1950s and 60s. Image:Tony Mott

My interest veered away from organised crime -- port and cigars crime, you might say -- more towards the small and obscure matters that define suburban Sydney in that era - three men in a pub plotting to rob a club manager of the Saturday night pokie takings; somebody falling off a train in the City Circle tunnel; a young mother knifing an abusive husband; a teenager stealing the milk money in a suburban street; a burglar shot dead by a nightwatchman at a service station.

Riffing on forensics

The mid-century’s underpinnings were duty, love, hate, dignity, stoicism, silence. To round out the picture: sport, drink, smokes, hobbies, women magazines, the Lodge and the parish priest. Sydney’s fibro and brick houses, their backyards and bedrooms, were full of crime and petty catastrophe.

The post-war years brought with them chemicals, additives, powders, pills, and tins of stuff with strange polysyllabic names that would kill pests, remove pimples, brighten house paint, settle nerves. It was the age of antibiotics, vaccines, new chemical industries. We worshipped dioxins, carcinogenic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), lead paint, asbestos.

Not surprisingly poison was a popular way to do away with those who’d done you wrong – rat poison, weedkiller, arsenic.

In the past 70 years, forensic investigation has gone from what might seem to many to be primitive and ham-fisted - predating DNA and computers - to something dazzlingly sophisticated, to sets of hugely important, hugely complex processes and procedures.

But do we over-romanticize forensics and forensic investigation? It’s become such a riff in novels, in movies and on TV! Police the world over tell us that the great majority of crimes and fatal accidents require no “detecting” at all – the material events are pretty clear and unambiguous, as much now as they were in the past.

Puzzle: An evidence photograph in the Graeme Thorne kidnapping-murder case. At one time police briefly suspected the kidnapper made a ransom demand from this phone box. Image: Estate of the late B K Doyle.

As 1950s training manuals instructed: First protect the crime scene to preserve the evidence, sketch each room, take fingerprints, shoe prints and preserve all other physical evidence.

The gathering of evidence in the Graeme Thorne kidnapping case in 1961 was meticulous, identifying and matching to their owners’ human hair, dog hair, twine, picnic rug fibres, seeds, mortar, soil. Detectives located a house where two different types of cypress pine grew, both of which were in the blanket the boy was wrapped in. On the case were botanists, chemists, zoologists, mineralogists, and herbarium experts.

Reading the records and talking to investigators from back then, I sense the aim of forensics wasn’t primarily to uncover who actually “done it”, but to compose a compelling narrative for the courts. Sloppy initial investigation of a crime scene could give a defence lawyer grounds to refute a prosecution case. A clear, dispassionate forensic account conversely played well in court, with judges and with juries.

I suspect forensics was a bit of a poor relation of professional policing. You can imagine it: the regular cops are out there wading into fights, performing dangerous rescues, dealing with underworld figures and occasionally facing acute danger, while the forensics boffins are looking under microscopes or developing photographs in the darkroom.

Yet forensics had to deal with the worst accidents and fatalities, suicides, all sorts of unimaginably horrible affairs – and not just have a quick glance and note what was where, but actually record the whole thing in great detail, take photos, record measurements, later on draw up precise diagrams.

Capturing the melancholy of suburban life.

Honorary Associate Professor Peter Doyle’s books include the novels The Big Whatever (2015), Crooks Like Us, (2009), City of Shadows (2005), The Devil’s Jump (2001), Get Rich Quick (1996), and Amaze Your Friends (1998). He is the winner of two Ned Kelly Awards (for Best First Crime Novel, 1997, and Best Crime Novel, 1998).