Addiction, violence, aggression, social withdrawal: video games have been in the crosshairs for a litany of negative impacts.

Researchers at Macquarie University, however, are working on the premise that video games can have positive impacts, too - that just as pilots use simulators to learn and hone their flight skills, video games could be an opportunity to develop our moral skills.

Real life impact: Philosopher Dr Paul Formosa has identified four moral skills players can acquire by playing video games.

Some of the same sorts of moral skills we use in real life, can be used in games, and games can interact with those skills and develop them and that’s really what we’ve been looking at in our research,” says Dr Paul Formosa, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Philosophy.

“A lot of the media around video games is pretty negative and a lot of the research, too, has been on the negative effects – meta-analysis shows there is some real-life impact of video games but it’s not huge and it’s not shown in every single study - but we’re far more interested in the positive effects, which are much less studied.”

Formosa is part of a multidisciplinary team that, based on its theoretical findings, is building a video game to be used in experiments looking at how different design features can engage with various moral skills.

Those features include timers and how they affect decision making, and whether so-called virtue meters, which award points for good deeds and vice versa, instrumentalise morality so that players seek to maximise the meter rather than engage with the moral issues.

‘It’s important not to have a moral panic’

Formosa says the research has employed moral psychology to pinpoint four moral skills (see below) that people need in real life and that games can interact with.

Indeed, many commercial games already engage with these skills. Examples include Papers, Please, in which the player is an immigration officer checking papers on the border of a totalitarian state; The Walking Dead, which holds the player to account for their life-and-death choices and asks them to justify their actions; and This War of Mine, where you’re a civilian stuck in a war zone having to make all sorts of tough choices in order to survive.

Fortnite – the shoot-‘em-up game du jour – does not, in case you were wondering, engage moral skills, but Formosa does not have a problem with that, and emphasises that researchers are not suggesting violent games should not be played.

“It’s important not to have a moral panic about games in general because they are not a homogenous group,” he says.

“People play them for all sorts of reasons. Some games require a lot more focus and engagement than others. A lot of people play short games on their phones for 5 or 10 minutes, Candy Crush and so forth, which are not supposed to be deep engagements; they are something to pass the time, and for some people they can relieve stress, so short instances of gaming like that can also have positive effects.

“We’re not saying that games like Fortnite shouldn’t be played, they have their role, but so do these other sorts of ethical games.”

Gamer stereotypes are out the window

Formosa says more than 50 per cent of people play games regularly. Many of them are women, and the average age is increasing, sitting right now in the mid-30s.

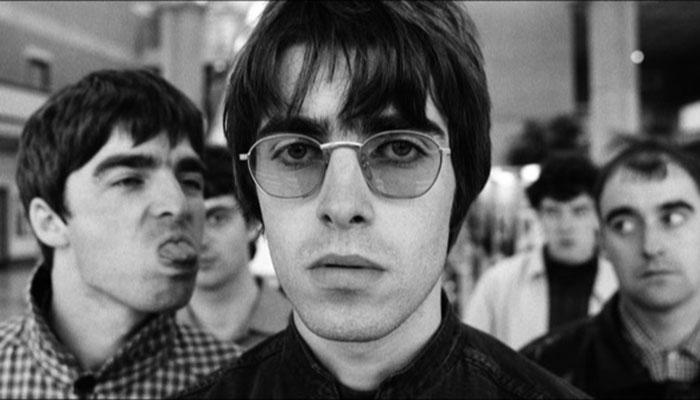

Beyond the teenagers: Video games are increasingly being played by women and gamers in their 50s say researchers.

“People have this image of the gamer as this teenage boy but that’s very inaccurate,” he says.

“When you look on the train, the 50-year-old woman is playing games on the mobile phone just as much as the 13-year-old boy; she may not be pulling out the Xbox when she gets home, but these are still forms of games.”

Dr Malcolm Ryan, Senior Lecturer for Games Design and Development in Macquarie’s Department of Computing, is leading the design of the experimental game which Formosa describes as Australian noir: “It’s set in the 1940s-50s, in a town cinema where there’s going to be a fire and a whole bunch of difficult moral judgments people will have to engage with.”

Writing the dialogue is Associate Professor Jane Messer, from the Creative Writing program in the Department of English, while Dr Stephanie Howarth, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Cognitive Science, has brought expertise in moral psychology to the project.

The moral skills the experimental game will seek to engage with include:

1. Moral sensitivity, which is about being sensitive to the very presence of moral situations which “we can often overlook or just ignore or not see,” Formosa says, “and you can see this in games where sometimes people might not even notice the moral issues at stake.”

2. Moral judgement. “Often games will have big moral judgements where you have to choose out of a or b, or do you sacrifice some people to save these other people, and that’s a really useful way to practise and develop your moral judgement without real-world stakes.”

3. Moral focus, which is about prioritising moral concerns when they conflict with self-interest.

4. Moral action. This involves the implementation of moral judgement which “might require a fair bit of perseverance or excellent communication skills or a lot of emotional maturity.”

“What we’re interested in is different ways games can be designed so they can engage with these different moral skills,” Formosa says.

“We want to look at why some design choices might be better than others, and ultimately, hopefully, that would get incorporated into commercial games.”