Old people live in the past; they are conservative; they don’t think about the future. These statements could be describing stereotypical perceptions of older people in 2021, yet they go right back to the writings of Aristotle, says ancient Rome expert Professor Ray Laurence.

Stoic approach: The Death of Seneca by Peter Paul Reubens ... Seneca was among the Roman Stoic philosophers concerned with old age and living through it.

Aristotle’s writings and those of the Stoic philosophers are embedded in Western society’s thoughts about old people today, says Laurence. Intriguingly, most of the philosophy of Stoicism – a school of thought that flourished in ancient Rome and Greece – was written by old people, he says.

Stoicism is concerned with how a person must go through trials rather than steer away from them; how they must live with adversity and pain, and keep going in difficult conditions.

“Stoicism is almost like an old person’s philosophy,” Laurence says.

“It deals with old age as a disease you won’t recover from, and I guess that is the point of aged care homes today. Seldom do people come out of them and return home, so in that respect we see old age in a similar way to the ancient Romans.”

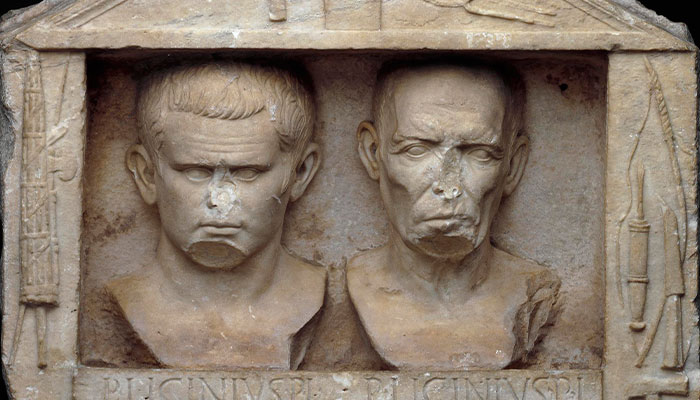

In ancient Rome, only about seven per cent of the population were over 60 – a huge difference to today, where in Australia about 16 per cent are aged 65 and over, a figure forecast to keep rising.

Striving for the good life

Laurence, who has researched and written extensively on growing old in ancient Rome, says that as well as regarding old age as an incurable illness, the Romans were concerned with what it meant to live a good life as an old person – also an idea that resonates today.

“The idea of old age and living through it was written about quite a lot,” Laurence says. “The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca talks quite categorically about it – he has an example where he goes to visit the farm on which he grew up and has owned his whole life, and he notices how dilapidated it is, and starts to think about his old age.

- A girls' guide to crashing through the glass ceiling

- Did frozen mudballs in space make life on earth possible?

“Then he meets an old man who claims to be his childhood friend, who was a slave, but he is much more decrepit than Seneca because he had fewer life chances.”

As well as philosophical writings, popular Roman literature talks of old people’s teeth falling out, and of people who can no longer eat and are fed liquids.

“And we do hear of people in old age who are in pain, who are really ill and they just simply decide to stop eating – they almost publicly announce it, that they have decided it is just not worth it to go on.”

An interest in wisdom

Laurence says evidence points to ancient Romans having the same life span as we do today. However, disease meant far fewer lived to fulfil it.

Respected: A Senator of ancient Rome Lucius Licinius Crassus ... in the Senate, the elderly would speak first.

“They had tuberculosis, malaria, cholera; they’d occasionally get outbreaks of small pox,” he says.

“We know more about upper class Romans living a long life, because that is just how it is in terms of the evidence … but we have lots of tombstones of people who are not rich and who are living a long time.

“Some claim they are 160 years old, which is quite a common exaggeration, saying you are older than everyone else.”

The elderly were valued for their wisdom and in the Senate they would speak first, but their opinions were also open to criticism – like those of Cato the Elder (234-149BC), who was famous for saying in every Senatorial debate that Carthage – an arch-rival Phoenician city-state in modern Tunisia – should be destroyed.

Old people became quite famous for how they’d lived and what they’d done, and also for their thinking.

As well as taking heed of the public statements of their older fellow citizens, people would visit them to see how wisely they lived their lives.

“They wanted to learn how you lived a good, long life, so old people became quite famous for how they’d lived and what they’d done, and also for their thinking,” Laurence says.

The lawyer, politician and writer Pliny the Younger describes the daily routine of the Roman Senator and consul Titus Spurinna (c24-104AD) during a visit to the home of his septuagenarian mentor.

Spurinna rises an hour after dawn, Pliny describes, and takes a three-mile walk during which he converses seriously with friends or has a book read aloud to him, which continues after the walk and as he goes out on a carriage ride.

Ancient faces: A marble relief depicting two freed slaves, one younger, one old ... only about 7 per cent of the ancient Roman population was aged over 60.

He then takes to his room to write, afterwards bathing and playing ‘heartily’ at ball, “for it is by means of this kind of active exercise that he battles with old age”, Pliny writes.

When dinner is served, it comes with a small theatre performance afterwards.

“There is no one whom I would rather take for an example in my old age … for no way of living is better planned than his,” Pliny writes.

Says Laurence: “Obviously if you had money it made a big difference. For one, you had slaves to look after you, or else you could pay someone.

“If you didn’t have money you just had to work – although the labour market is saturated in Rome – or rely on family, or begging.”

There was no social welfare, apart from free grain given out in Rome, but you had to be on a list: “There is a sense of patronage; a sense of duty that the rich would care for the poor, but that is also criticised and laughed at as a need that would not actually be fulfilled.”

The young wife as aged care worker

The concept that young wives would look after their older husbands was taken more seriously, says Laurence, translating into an aged care system of sorts.

![]()

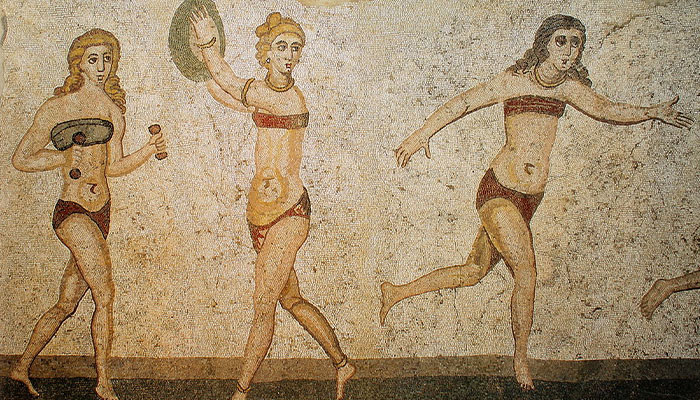

Active duty: An ancient Roman mosaic depicting women playing sport ... men would marry much younger women, creating an expectation that the wife would look after the husband in old age.

“This is a really intriguing area, the whole question about marriage ages in the Roman world,” he says.

“We know that men married their first wife at about age 25, and she would be about 10 years younger. If that wife died, which is quite likely in terms of lack of medical technology around child birth, the man would marry again, but this time to some one even younger than him.

“You constantly have an age differential whereby there is an expectation that the wife would look after the husband in old age – and an expectation that he would die first,” Laurence says.

- Solved – the site of Australia's first atronomical observatory

- A plant that tells you it needs water? Welcome to the future of SynBio

After the death of a husband they were provided for from his estate. Thus, this could be seen as a means of remuneration.

“We know that there are lots of widows in the Roman world, and they have money in their own right,” Laurence says.

“So there is a sense that the wife looks after the husband, but his wealth will maintain the life of the wife in the circumstances she was used to, in the house she lived in with her husband.”

Ray Laurence is Professor of Ancient History in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University.