Venus – Jupiter conjunction, March 2

The orbits of Venus and Jupiter around the Sun will make them appear very close together when viewed from Earth, and these two planets – which are among the brightest in our night sky – will appear closest on Thursday March 2 when seen from Sydney. They will be about half a degree apart, or about the size of the tip of your little finger when you stretch your arm up towards the sky.

Orbits align: Venus and Mars will appear close together on March 2. Image: Getty.

On a clear night, many different stars and occasionally planets are visible to the naked eye, usually appearing as a pinpoints of light in the sky - but planets can be distinguished from stars because they don’t “twinkle.” Stars are so far away that their light comes into our atmosphere as a ‘point source,’ passing through single air cells in our atmosphere, which scatter the light as it moves through different temperatures and densities, making it look twinkly. Light reflected from nearby planets is spread more broadly on entry into Earth’s atmosphere, so planets appear as steady, shining points in the sky.

From Sydney, the two planets will become visible around 19:46 AEDT, above the western horizon, as dusk fades to darkness, and will then sink towards the horizon, setting more than an hour after the sun at 20:54.

Partial and Total Solar Eclipse – April 20

When the moon passes between Earth and our Sun on April 20, its shadow tracks across a small part of the Earth’s surface, causing a total solar eclipse in a some areas, and a partial eclipse across much larger, surrounding areas.

In Australia, Exmouth, on the north-west cape of Western Australia, will experience a total eclipse, along with parts of southeast Asia and Antarctica, while a partial eclipse will be seen across most other parts of Australia.

This one promises to be a relatively rare “hybrid eclipse.” The Sun–Moon–Earth spacing provides a just-barely annular (ring-like) eclipse at both ends of the path (the points on Earth farthest from the Moon) and a brief total eclipse in the path’s middle.

From Sydney, the eclipse will appear as if a small nibble has been taken out of the sun from two sides.

Never look directly at the sun at any time including during a partial or total eclipse, as the intense light and heat can lead to permanent vision loss.

Partial Lunar Eclipses – May 6 and October 29

Two partial lunar eclipses will appear this year. On May 5 in the northern hemisphere (May 6 in Sydney), the Moon will pass through the faint, outer part of Earth’s shadow called the penumbra, leading to a less-dramatic, subtle-looking penumbral lunar eclipse appearing in Africa, Asia and Australia, making the moon appear darker and somewhat redder than usual.

Naked eye: No equipment is needed to watch Earth's shadow fall across the moon in a lunar eclipse. Photo credit: NASA / Robert Fedez

A partial lunar eclipse on October 28 will be visible in Europe, Asia, Africa, parts of North America and much of South America on October 28 - and on October 29 in Sydney. Partial eclipses occur when the Sun, Earth and Moon don't completely align, so only part of the moon passes into shadow – but where the Earth blocks the Sun’s light from reaching the lunar surface, the Moon’s surface will appear to turn reddish.

Blue Supermoon – August 30

Every two-and-a-half years, two full moons will occur within one month, and the second full moon in a month is known as a blue moon.

In 2023, two full moons will occur in August, both of them ‘supermoons’ that appear brighter and larger in the night sky than usual, as the moon’s orbit brings it closer to Earth. (This can also drive higher-than-usual tides.)

In the Southern Hemisphere, the August full moon is called the ‘snow moon’ – a name that will apply to the first full moon of the month, on August 2.

Meteor Showers

Meteor showers involve tiny fragments of rock shed by a comet or asteroid, many smaller than a grain of rice, which burn up in the atmosphere of Earth as our planet passes through a debris trail. They are great to watch, and during the more spectacular periods, the sky can appear to rain down shooting stars every few minutes.

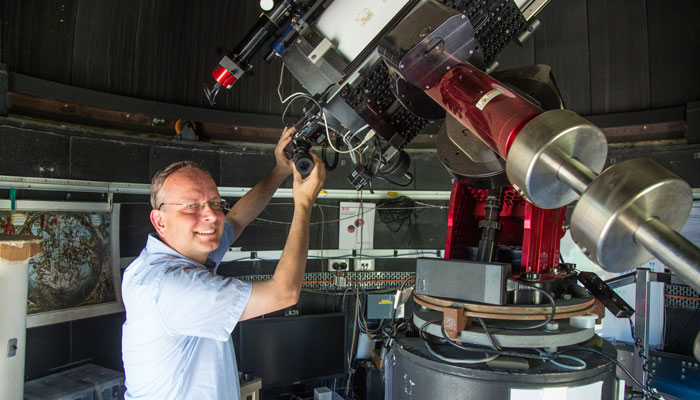

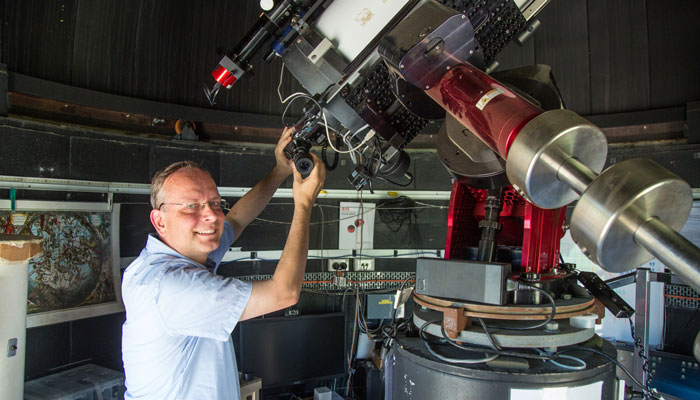

Astronomical advice: Professor Richard de Grijs recommends driving to locations which are unaffected by light pollution for the best views of night sky spectacles.

If you live in an urban area, try driving to a place not littered with city lights, because in areas unaffected by light pollution, in peak periods meteors could be visible every few minutes from late evening until dawn.

Find an open area with a wide view of the sky. Make sure you have a chair or blanket so you can look straight up. And give your eyes about 20 to 30 minutes to adjust to the darkness (without looking at your phone) so the meteors will be easier to spot.

Here are some of the more dazzling displays we can expect in our region this year:

Eta Aquariids meteor shower: May 6–7

Halley’s Comet last crossed Earth’s orbit in 1986, leaving trails of debris that intersect with Earth’s orbit twice each year. Eta Aquiariids is the name given to the first debris trail, in May, which features about a week’s worth of viewing of swift meteors, peaking around 2 am on May 7 in Sydney. The Eta Aquariids are known for their high proportion of luminous extended trails that persist in the sky for several seconds after the meteor has disappeared. (Halley's Comet will make another appearance around the year 2061.)

Perseid: August 11–14

The Perseid meteor shower occurs as Earth passes through the trail of debris shed by the Swift–Tuttle comet, an icy ball of rocks and gas 26 kilometres wide made up of remnants of the formation of our solar system, which last crossed Earth’s orbit in 1992 and returns every 133 years. At its peak, Perseid can display up to a hundred shooting stars in an hour. This year, the peak will occur around 5 am AEST on August 14.

The Orionids: October 22

This meteor shower is the second time each year that Earth intersects with Halley’s Comet trail, and while the Orionid shower typically produces less meteors (around 20 per hour at their peak), these can be very fast and bright.

Geminids: December 13–14

The Geminids are one of the year’s more spectacular meteor showers, and one of the few that don’t involve a comet; instead, this debris trail of dust and rock fragments comes from the near-Earth asteroid 3200 Phaethon.

Shooting stars: Meteor showers are one of the most entertaining events for backyard astronomers to view. Image: Getty.

At the peak, there may be up to 150 meteors each hour, many bright and intensely coloured, with medium-slow velocity. This year Geminids peak around 11:40 pm AEDT on December 14 in Sydney, just after a new moon – offering good visibility on a clear night, without moonlight interfering.

Professor Richard de Grijs is a scientist in the Macquarie University School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences.