It is no secret that being involved in an extremely traumatic event can have a serious impact on someone’s health and wellbeing. For some people - up to five to 10 per cent of the community - feelings of grief and sadness tip over into Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a condition that can last for months or even years if untreated.

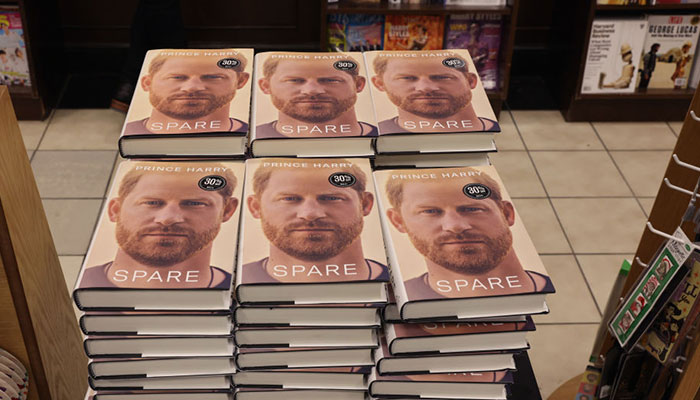

At risk: Members of the military, police, paramedics and emergency department hospital staff are susceptible to PTSD, as are young children like Prince Harry who experience the sudden death of a parent.

PTSD is associated with experiencing or witnessing life-threatening or terrifying events. It can be related to a single triggering incident, such as a car accident or a violent attack, or to a series of events, such as ongoing abuse.

Both adults and children are susceptible to PTSD, and for young children, the sudden death of a parent and the upheavals that follow can be the trigger.

When does stress become a disorder?

Macquarie University Professor of Psychology, Maria Kangas, says the term trauma is used loosely in the community to refer to any stressful or upsetting event, but the clinical definition of PTSD is much stricter.

“A diagnosis of PTSD requires a person to be experiencing four broad groups of symptoms for more than four weeks,” she says. “These are intrusive memories of the traumatic event, avoiding thoughts, situations or locations associated with the incident, hyper-arousal, and a change for the worse in how the person perceives themselves, other people and/or the world.”

Symptoms from the four clusters vary from person to person, but may include immersive flashbacks, nightmares, insomnia, trouble concentrating, mood disturbances, self-destructive behaviour, substance abuse, overwhelming feelings of guilt or shame, feeling numb or detached, being easily startled or constantly on guard, feeling that the world or specific parts of it is no longer a safe or fair place, and feeling that people cannot be trusted.

A diagnosis of PTSD requires a person to be experiencing four broad groups of symptoms for more than four weeks.

While anyone can develop the condition after a life-threatening event, some professions are at particular risk of secondary PTSD due to what they witness at work.

Members of the military, first responders (police, paramedics, fire fighters and emergency service volunteers), emergency department staff in hospitals, detectives, and journalists are all susceptible, as are investigators who have to view upsetting material such as images of child abuse.

Working through pain

Kangas says following any traumatic event, it is natural to feel upset and needing some time to recover and process (‘make sense’) what has happened.

Finding peace: Resilience has an important role to play in PTSD and can be learned, says Professor Kangas.

In some cases, there can be overlap between the symptoms of PTSD and traumatic grief following the sudden, traumatic loss of a loved one.

“There is no ‘right’ timeframe for recovery, but if you’re feeling that you should be getting back to normal and you’re unable to do so, then you should think about seeking some assistance.

“If a friend or loved one has gone through a life-threatening event, then signs to watch out for include being different from how they used to be, being more on edge, more irritable, shutting themselves off, and ignoring normal activities like self-care.

“In the short term, these things are fairly normal, but if they go on for more than a few weeks, into a month, you may want to tentatively reach out and see if you can help.”

Resilience and recovery

Just as not everyone who loses a loved one will suffer from traumatic grief, not everyone who experiences a life-threatening event will develop PTSD.

At any one time, between five and 10 per cent of the adult population will be experiencing the effects of PTSD.

Kangas says general resilience has a big role to play in PTSD prevention, as does the existing state of a person’s mental health and what else is happening in their life, and their social support structure.

“Resilience is something we can learn,” she says. “How we cope ordinarily will determine how we cope when we encounter a serious stressor, so learning to cope with our emotions in relation to ordinary life events is beneficial," Kangas said.

Both PTSD and traumatic grief can be treated effectively ... but the sooner you seek help the better your chances of making a full recovery.

“There is no one way of coping with stress that will help everyone, but we can have a repertoire of coping strategies, including talking through your problems with friends, family or spiritual advisors, reflecting on issues that are worrying you through journalling, engaging in activities that can distract you from the problem for a while, and reaching out for additional support when you need it.

“Social support in the form of friends, family or community is a big factor, and it’s important to make yourself open to offers of support rather than shutting yourself off.”

Even for someone without high levels of resilience, a full recovery from PTSD is possible.

- Education rethink ahead as ChatGPT hits classrooms

- Emily review: A beautiful portrait of what might have been

The most effective evidence-based psychotherapy treatment method is trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TFCBT). This involves between eight and 20 weekly sessions with a qualified therapist, where the person talks through their trauma in a safe environment, is gradually exposed to traumatic situations during the sessions and in the outside world, and learns adaptive coping strategies.

Another evidence-based treatment is known as eye-movement reprocessing and desensitisation (EMDR), where the patient is exposed to traumatic situations while concentrating on another type of stimulus, such as sound or blinking lights.

“Both PTSD and traumatic grief can be treated effectively, but as with most problems, the sooner you seek help, the better your chances of making a full recovery in a shorter period of time,” Kangas says.

“The most important thing is to be aware of what’s available and seek help when you feel you need it.”

Professor Maria Kangas is the Head of Macquarie’s School of Psychological Sciences and a member of the Centre for Emotional Health at Macquarie University.

The Centre for Emotional Health conducts research to further the understanding of emotional disorders, and offers treatment programs for adults and children at its clinic.