For two million years, giant apes roamed through the jungles of today’s southern China before mysteriously dying out, despite other ape species thriving.

Now, extraordinarily in-depth research using lasers to date 600,000 year old soil can reveal the reason for their disappearance.

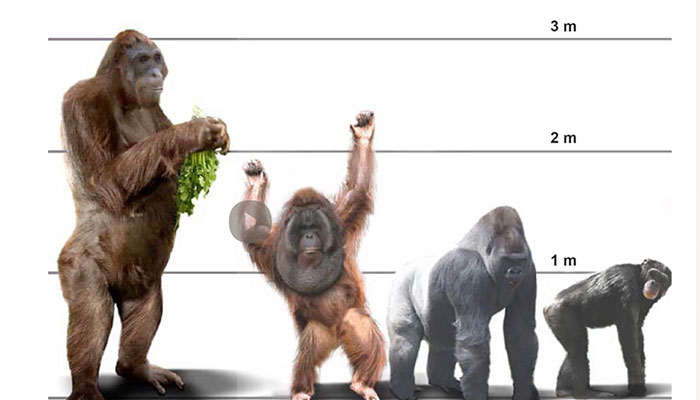

Gigantopithecus blacki (G.blacki) stood around three metres tall, weighed over 250 kilograms, and is the largest primate species ever recorded.

The only traces of this mighty ape to date are a few thousand teeth and four partial jawbones. Countless hours of laboratory work by scientists in Australia, China and the USA to map the evolution of this species from its origin to extinction, has now delivered definitive proof of both the time and the cause of its intriguing disappearance.

Associate Professor Kira Westaway, a geochronologist from Macquarie University, is the co-lead author of a new paper from this international team published in Nature on 11 January.

“To answer this longstanding puzzle, we took a comprehensive regional approach, applying robust dating techniques to the sediments surrounding the buried fossils,” she says.

Associate Professor Westaway has spent nearly a decade digging in the remote caves of southern China’s karst regions, often in darkness, to collect clues hidden in molecules of the sediment surrounding fossilised teeth of G.blacki buried for over 200,000 years.

Solving the puzzle

“The key to solving this mystery lay in establishing the exact time G.blacki disappeared from the fossil record, then reconstructing the changes in environment and the apes’ behaviours in the lead-up to its extinction,” says Associate Professor Westaway.

Deep dive: Associate Professor Kira Westaway, pictured, spent years excavating buried fossils and surrounding soil in southern Chinese caves to pinpoint when the giant ape became extinct. Image supplied by Kira Westaway

Using techniques such as luminescence dating, Associate Professor Westaway can pinpoint how long the minerals surrounding a fossil have been buried, to build a picture of what was going on in the environment at the time.

The international team used six different dating methods on cave sediments and fossils to demonstrate beyond doubt G.blacki (affectionately nicknamed Giganto) became extinct between 295,000 and 215,000 years ago – much earlier than previously assumed.

The buried fossil remains of G.blacki are only found in cave deposits in southern China, between the Yangtze River and the South China Sea.

“The limestone caves in this region form incredible sediment traps that are a treasure-trove for fossils,” Associate Professor Westaway says.

The species first came to international attention in 1935 when palaeontologist Gustav von Koenigswald spotted an enormous molar tooth in a Hong Kong apothecary sold as a ‘dragon’s tooth,’ then classified the ape after finding four more teeth from the species in similar shops.

Extensive field trips into southern China in the 1950s unearthed over one thousand individual teeth and four partial jawbones from caves across the region. But despite 85 years of searching, G.blacki teeth have not emerged elsewhere, and no other bones have been found.

Lighting the way

In this decade-long study, the research team included reconnaissance groups who surveyed hundreds of caves in the limestone landscape to identify those with the highest likelihood of G.blacki fossils.

Trekking through thick jungles with local guides, scaling cliffs and scrambling through deep caves to uncover prehistoric clues; while the sample-collecting process may sound like an adventure movie, Associate Professor Westaway says the exciting breakthroughs happen in the laboratory.

Remote: Researchers navigated the steep karst mountains of southern China to access caves containing fossils of G. blacki dating back hundreds of millennia. Image credit: Professor Yingqi Zhang, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS)

In the lab, she uses lasers to measure light-sensitive signals emitted by common minerals like quartz and feldspar found in the soil and rock around fossils, to calculate when the mineral was last exposed to sunlight and the age of the fossil’s burial.

The Tooth Whisperer

With nothing but teeth, a few jawbones and the dirt around them, the researchers have constructed a thorough and convincing picture of Giganto’s two-million-year lifespan, and its final decline.

Associate Professor Westaway says her co-author Associate Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau from Southern Cross University played an essential role in revealing how the behaviours of the ape changed over time.

“We call Renaud the ‘Tooth Whisperer’ because of how he maps elements in the teeth so we can understand how far and where Giganto travelled for water, and how he analyses trace elements to identify their diversity of food.”

Ultimately the team found as the environment changed around it, Giganto didn't adapt, and its reduced mobility and reliance on low-nutrient fall-back foods caused its eventual extinction.

Changed climate

“From 2.3 million years ago, this region was a mosaic of thick forests with patches of grassland where Giganto thrived on a varied diet with fruits and flowers year-round and plentiful water,” says Associate Professor Westaway.

Giganto: Gigantopithecus blacki (G.blacki) stood around three metres tall, weighed over 250 kilograms and is the largest primate species ever recorded.

Giganto shared its forest with a wide variety of other species, including Pongo weidenreichi – an ancestor of today’s orangutan.

But around 700,000 to 600,000 years ago, the region’s climate morphed into one with more distinct wet/dry seasons, and the structure of the forest communities changed from dense jungle to forests with ferns and open grasslands that could catch fire.

- VIDEO: Ramses: golden treasures of the superstar pharaoh come to Sydney

- Scamming the scammers: new AI fake victims to disrupt criminal model

Orangutan P. weidenreichi adapted, its body became smaller, and it survived by foraging in the forest canopy where there were more food options.

Not so Giganto: as its food sources and foraging range reduced, the ape got even larger and, confined to the forest floor, ate bark and other low-nutrition back-up food sources when its favourite fruits were out of season.

By the time these teeth began to disappear from the fossil record as Giganto’s numbers dwindled, microscopic imagery of teeth from apes living in this time period shows signs of poor nutrition and chronic stress, indicators of a species in decline.

“This story is a lesson in extinction,” says Associate Professor Westaway. “Ultimately, its inability to adapt to changed conditions led to the demise of the greatest primate to ever inhabit the Earth."

Associate Professor Kira Westaway is a geochronologist in the School of Natural Sciences in the Faculty of Science and Engineering.

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.