As a fiction writer and science researcher, I’ve been deeply involved for a decade in communities interested in outer space, such as astronomers, space lawyers, ethicists and space scientists.

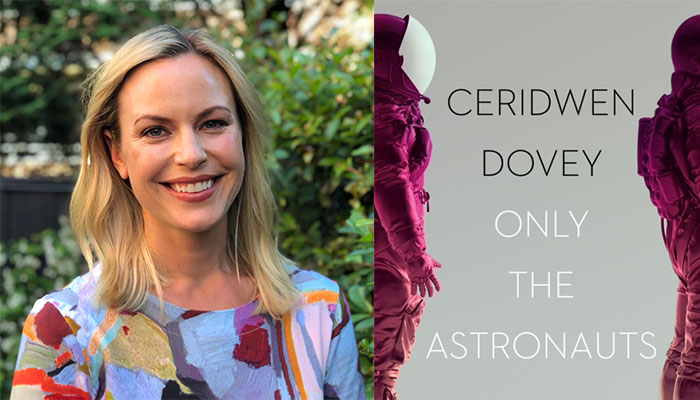

New book: Author Dr Ceridwen Dovey, pictured, tells the tales of human-made objects drifting in space from their perspectives.

During this time, I began to notice that many people feel complex emotions about objects launched into space. Space scientists sobbed when the European Space Agency’s beloved Rosetta orbiter was intentionally crashed into an asteroid in 2016. There were outpourings of heart emojis from followers in response to social media posts on NASA’s accounts for the Voyager spacecraft.

Margaret Weitekamp, a curator of space history at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, described to me how people gaze reverently at the museum’s flown spacesuit collection. Sweetgum, redwood, sycamore, loblolly pine and Douglas fir seeds were taken into space on the Apollo 14 mission, and on their return planted around the U.S. to grow into Moon trees that people worship as magical.

Whenever I encountered one of these true stories about a space object, I’d have the creative impulse not only to excavate the object’s sociological meaning as an essayist and science writer. I also wanted to use experimental modes of fiction writing to look back at human beings from the perspectives of the object themselves. A space object’s-eye view of humanity, in other words. By becoming their medium, what else might come into view?

I could see how this challenge could deepen my own entanglements as a writer with the thorny questions of authorship, voice, representation and empathy. My aim was to invest these objects with human qualities and capabilities: language, feeling, thought, agency and an awareness of their relationships with humans and other space objects alike. The trick was to use the object to get at the inner lives of the humans who’d made them and thrust them out into space.

These space object narratives are now at the heart of my latest book of stories, Only the Astronauts (Penguin Random House, 2024). In each tale, I write from the point of view of a real space object launched since the start of the Space Age in the late 1950s. This framing lets me use techniques of speculative fiction to engage with elements of space history and the ethics of contemporary spacefaring.

In my stories, Starman – the lovelorn mannequin orbiting the Sun in his cherry-red car – pines for his creator. The first sculpture ever taken to the Moon is possessed by the spirit of Neil Armstrong. The International Space Station, awaiting future deorbit and burial in a spacecraft cemetery beneath the ocean, farewells its last astronauts. The Voyager 1 space probe (carrying its precious Golden Record) is captured by Oortians near the edge of the solar system and is drawn into their baroque, glimmering rituals.

- Star-gazing in broad daylight: how a multi-lens telescope is changing astronomy

- Massive galaxies older than we thought: discovery

By turns joyous and mournful, these object-astronauts are not high priests of the universe but something a little … weirder. From their inverted perspectives, they observe humans both intimately and from a great distance, bearing witness to a civilisation unable to live up to its own ideals.

And yet each object still finds in our planet – in their humans – something worthy of love. My space object narrators let me escape certain literary assumptions about human narrators, allowing me to float free from the constraints of realism and create an allegorical atmosphere inspired by legendary writers of fables like Italo Calvino and José Saramago.

I visualise this method of using objects to tell stories as a way of orbiting around the human psyche as some of these objects orbit Earth, peering back at us in all our beastliness, sweetness and despair.

Only the Astronauts, published by Penguin, was included on the Prime Minister's Summer Reading List 2024.

Dr Ceridwen Dovey is a Research Fellow in the Macquarie University School of Communication, Society and Culture in the Faculty of Arts.