‘Coo-ee’ – an iconic Australian bush call for over two centuries – was one of the first Aboriginal words used by early colonisers, who took it from the Dharug word 'guu-wii' – meaning 'come here'.

Videographer: Sophie Gidley

It's a fitting name for a new citizen science project run out of Macquarie University to gather Indigenous language and culture information from people all over Australia via an easy-to-use web-based app.

The project is part of an international venture by linguists at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. All of the data collected will be stored and managed at Macquarie and made available to Indigenous communities.

“Language isn’t just about communication – it’s also a repository of identity, culture, history, traditions and memory,” says Professor Bronwyn Carlson, who heads the Department of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University.

One of the most important parts of the COOEE project will be its ability to have Indigenous communities themselves identify the research questions they want answered, and the way they want to use the data that will be collected online from the project, she adds.

It’s so important that language is taught by people from the community rather than linguists.

“Citizen science is all about letting people’s voices be heard, and nowhere is that more important than when collecting language and culture material that the community themselves want to collect,” says Dr Nanna Haug Hilton, Associate Professor of Sociolinguistics at the University of Groningen and lead researcher on the COOEE project.

Dr Michael Donovan is the Academic Director, Indigenous Learning and Teaching, at Macquarie, and a Gumbaynggir man from the north coast of NSW who has met with the research team from the Netherlands.

Donovan knows all too well the importance of recording languages at risk of disappearing – neither he nor his siblings learned the family’s language during their childhood in Sydney, though he recalls hearing his father and grandfather ‘falling into language’ once when they were arguing.

Fear of speaking out: Dr Michael Donovan recalls how his family were cautious about speaking their native Gumbaynggir language so as to protect him and his siblings.

“The whole house just stopped,” he said. His grandmother had been removed from her family so his parents were very careful to keep language hidden to keep the family safe, Donovan adds. “My parents did it to protect us all.”

His father and grandfather are no longer alive and Donovan says he has used online tools for language revitalisation to try to learn some of the Gumbaynggir language.

“It’s so important that language is taught by people from the community rather than linguists,” he says. “Because English is the dominant language of Australia, even for most Aboriginal people, much of our understanding is based on linguists, who re-interpret Indigenous language from a non-Indigenous standpoint and can misrepresent language interpretations through hearing the language from this standpoint.”

Handing back power to the community

There is now international recognition of the value of Australian languages and the rich and important information they hold that often dates back thousands of years. Particularly in oral cultures, the loss of a language means the loss of a deep body of knowledge held within.

Linguists are also recognising the importance of community voices and this project is trying to hand power back to the speakers of minority languages, according to Dr Haug Hilton.

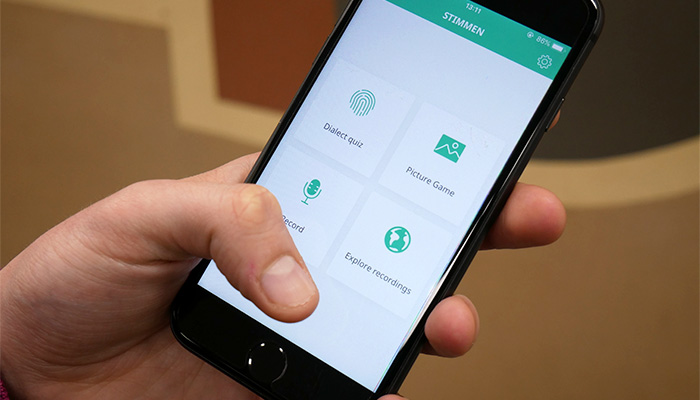

The COOEE project involves repurposing the University of Groningen’s existing app called Stimmen fan Fryslân (Voices of Fryslân) which collated the many dialects of the minority Frisian language used by half a million people in the north-east of the Netherlands and parts of Germany.

The Stimmen fan Fryslan app lets users record and add spoken language themselves and also add more information such as the background and meaning of words.

Storing speech: The Stimmen fan Fryslan app is currently available in English, Frisian and Dutch.

There are already more than 46,000 recordings from native speakers of Frisian – providing an invaluable resource for speakers, teachers, linguists and even speech technology developers who can train artificial intelligence and ensure that many varieties of language survive into the digital age.

Options include a game where you are asked to name as many pictures as possible (while recording your response). The app can ‘guess’ where your accent comes from based on your recorded response to a series of short questions, and you can also contribute a short public recording – such as a story or joke.

- What is the easiest language to learn?

- Carpe diem: Adults learn Latin in rising numbers

- Meet Elias, trilingual at 3

"We can use any of these in an Australian version," says Hilton. She is quick to add that the whole point of a citizen science project is that the outcomes are not pre-defined; it’s up to the participants to say what they want the project to deliver.

“Projects like this are about including the voices from groups who are under-represented in science,” she says. Examples of data to come out of other projects are collections of narratives that can be used for research in sociology, anthropology and cultural studies, or information about linguistic systems, language use and language proficiency that are crucial to research in linguistics, hearing, and the educational sciences.

The resilience of Indigenous language-speakers over the past 231 years is remarkable.

Marcela Huilcan Herrera from the University of Groningen (who is originally from a minority language group in Chile, the Mapuche people), was in Australia from February to April to meet with a collaborative research team from Macquarie University’s Indigenous Studies and Linguistics departments.

Huilcán also met with a number of representatives from Aboriginal groups including people from the Dharug, Gumbaynggirr and Birpai communities and the Muurrbay Language Centre, spoke to Wiradjuri and Dharawal community members and met with a range of academics from Linguistics and Indigenous Studies, to find out their interest in the project and the data and what they would like to see.

Year of Indigenous Languages renews the focus

Globally, around 40 per cent of the world’s 6700 languages are endangered, most of these Indigenous. That’s why the United Nations declared 2019 the Year of Indigenous Languages – and in Australia, where around 90 per cent of remaining Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages are in danger of disappearing, there’s renewed focus on the importance of preserving what is left.

"Before Australia was invaded, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across the continent spoke between 300 and 700 languages," says Donovan. About 10 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people surveyed in the 2016 national Census reported speaking an Australian Indigenous language at home, with around 150 different Australian Indigenous languages identified. Many of these languages are ‘sleeping’ – meaning only a few people remain who can speak it fluently.

“The resilience of Indigenous language-speakers over the past 231 years is remarkable when considering that Australia’s governments, schools and settlers prevented Aboriginal people from speaking their languages, in some cases right up until the 1970s,” says Carlson.

Deeper meaning: Language is more than just communication – it’s also a repository of identity, culture, history, traditions and memory, says Professor Bronwyn Carlson.

However many Australian schools still don’t support children’s education in their languages, and the National Curriculum for schools still states that all curriculum achievements are expected to be demonstrated in Standard Australian English.

Things are beginning to change; Wiradjuri is now taught more than Spanish in Australian schools. Through member groups of the First Languages Australia network and local initiatives, there are hundreds of projects around Australia working to preserve and spread Australia’s first languages.

The COOEE project may provide a valuable tool that can help Indigenous communities around Australia to ensure that thousands of years of cultural heritage survive into the digital age.