As the use of artificial intelligence in the workplace accelerates, the future of ‘meaningful work’ comes under the microscope.

Meaningful work is employment that has worth, significance or a higher purpose. Ideally, it should be engaging, varied, require the use of complex skills, benefit others and be freely chosen.

AI is the ability of computers and other artificial entities to do tasks that would, were a human to do them, require intelligence. For example, the ability to reason, plan, problem solve and learn from experience.

The impact of AI on meaningful work is both significant and mixed, say Associate Professor Sarah Bankins and Professor Paul Formosa in their paper, The Ethical Implications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) For Meaningful Work,published in the Journal of Business Ethics.

AI has the potential to make work more meaningful for workers by undertaking less meaningful tasks for us and amplifying our capabilities, say the authors. But it can also make work less meaningful for others by creating new, boring tasks, restricting worker autonomy and unfairly directing the benefits of AI away from the less skilled.

Providing meaningful work is ethically important, state Bankins and Formosa, as it “respects workers’ autonomy and their ability to exercise complex skills in helping others, contributes to their wellbeing and allows them to flourish as complex human beings”.

Embedded with the frenemy

The Stanford University 2023 AI Index Report shows that technology and telecom sectors, financial services and business, legal and professional services are embedding AI in at least one business function.

AI is also making its presence felt in frontline professions such as nursing and teaching.

“We see it helping to manage patient flow and administration in hospitals and to power chatbots for on-demand customer service,” says Bankins. “AI also promises many benefits for education, such as enhancing personalised learning and feedback.”

Probing the links between AI and meaningful work, she says, “can help organisations more strategically think about their use of AI and what it means for their workers’ experience of meaningful work”.

Missing from a discussion about the relationship so far has been the question of ethics. So where do ethics sit in the AI world of meaningful work?

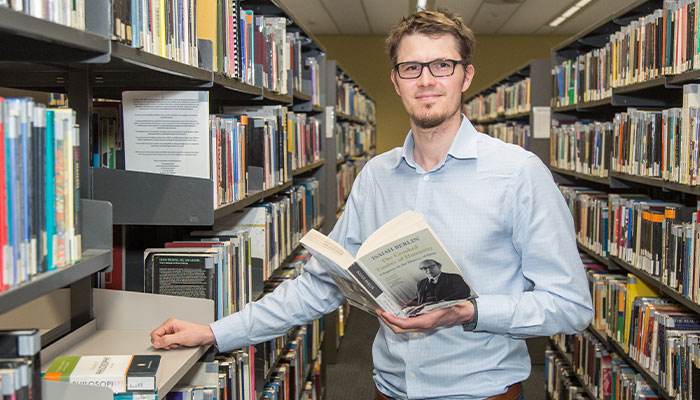

No substitute: Professor Paul Formosa, pictured, says regardless of future AI advancements, humans will still be needed in workplaces for exercising judgement, being creative, communicating well and interacting with stakeholders.

“To see your life as meaningful is to see it as rich, valuable and worth living, and that is clearly of ethical significance,” says Formosa, a philosopher.

“While we derive a sense of meaning from many things, such as our relationships with other people and our hobbies and interests, an important source of meaningfulness for many people is the work that they do. Work allows us to exercise and hone our skills for the benefit of others, while developing rich relationships with co-workers.

“AI threatens to dramatically change our workplaces and the work that we do, and it therefore raises important ethical questions concerning what we should do about it,” he says.

It is not enough to just look at what AI is being used for. Instead, Associate Professor Bankins and Professor Formosa say we need to look at what is left – or what new work there is – for human workers to do in order to understand the implications for meaningful work.

For example, if a hospital uses machine learning to help manage patient flow and minimise patient wait times this should free up staff to do other things.

“But what other things? This is where thinking about job design is important,” says Bankins. “Can those staff now do work that is more interesting, better uses their skills or gives them more interaction time with patients? Or will they be given other similar work which does not change their job a great deal, or will they be given more boring and menial work which changes their job for the worse?”

New ways of working: Associate Professor Sarah Bankins, pictured, says humans will be free to take up new and more interesting tasks with AI tackling less meaningful work such as minimising patient wait times in hospitals for example.

Accepting AI in the workplace takes time, she says. There is a lot of fear around what new technologies mean for humans.

“For me, helping staff transition to more AI-enabled workplaces means educating and informing workers, designing AI-augmented jobs well and being clear about what working with AI will mean for people’s jobs – and having a supportive organisational culture.

Banking on human bias

While many companies mention or claim to endorse ethical AI guidelines, says Formosa, it is one thing to make claims about wanting to be ethical and another to follow through when there are large financial interests at stake.

For example, several AI firms have played up the potential apocalyptic dangers of rogue AI, but this can sideline the more ‘mundane’ dangers of misinformation and bias, appropriation of training data or privacy violations which may impact their bottom lines.

Even as AI can do more and more impressive things, at least in the foreseeable future I believe humans will retain unique and needed skills in the world of work.

Arriving at an optimum ethical deployment of AI requires weighing up costs and benefits. There are some things workplaces will always need humans for, however.

“Even as AI can do more and more impressive things, at least in the foreseeable future I believe humans will retain unique and needed skills in the world of work,” says Bankins.

For example, exercising their judgement, being creative, communicating well and interacting with stakeholders, critiquing and contextualising the outputs of new technologies, and other tasks and roles that we haven’t imagined yet.”

- The surprising benefits of TikTok for teenagers: new research

- Hungry caterpillars: a new hero emerges in the war against plastic waste

Formosa cites evidence that people have a ‘human bias’, preferring to interact with other humans rather than AI.

“AI can tend to be ‘brittle’ and perform poorly in novel situations outside its training data, which means humans are needed to ‘sense check’ its outputs in critical contexts,” he says. “But researchers are already working on ways to make our interactions with AI more ‘human’ and improve AI’s robustness.”

Associate Professor Sarah Bankins is from the Department of Management at Macquarie Business School.

Professor Paul Formosa is Head of the Department of Philosophy at Macquarie University and Co-Director for the Macquarie University Ethics and Agency Research Centre.

Discover Macquarie University's Master of Information Technology program

* This story was first published in July 2023.