Published in 1897, the novel Dracula is most popularly remembered for its portrayal of a powerful and tangible Gothic horror, with its looming Transylvanian castle, lamplit carriage journeys through wolf-infested mountain forests and of course the monstrous vampire Dracula and his spider-eating servant Renfield.

However it is equally concerned with the horrors we cannot see, with questions about the mind and disordered states of consciousness such as dreams, hypnotic trances and madness. And particularly with the mind’s unsettling permeability and the dissolution of the borders between oneself and others, whether human or supernatural.

This was the era of mesmerism and its descendant hypnotism (Freud would publish his famous The Interpretation of Dreams only two years after Dracula), and such concerns were often bound up in the spiritualist claims of communion with the dead.

Kip William’s Dracula chooses to emphasise this cerebral element of Stoker’s novel. The book’s powerful sense of landscape and setting is all but dissolved; the set is often stripped back only to its barest elements – a chair, a coffin, a desk. Instead, a focus on the mind takes centre stage. While this element itself is not new, and perhaps nor are the questions it provokes, the production’s triumph is in the innovative technological methods it uses to foreground these themes, and just how fitting they are for a twenty-first-century adaptation of Stoker’s story.

As mesmerising as Newman’s flawless delivery of so many characters is, almost her equal on stage is the spectre of technology itself.

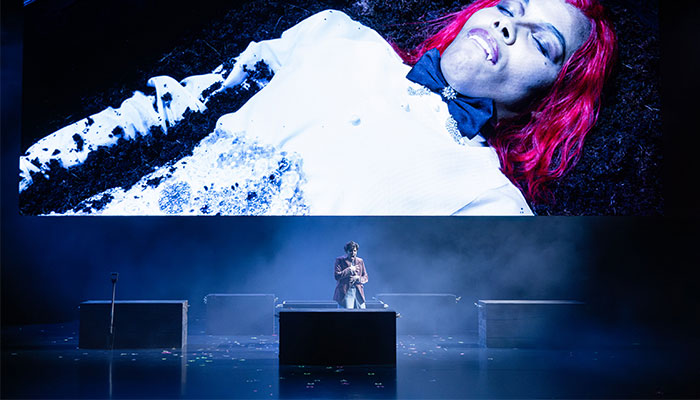

Our first clue arises in the haunting opening sequence, in which a single actor writhes on the stage floor; they are also filmed from above and the live image is displayed on a screen dominating the stage. Soon, the image distorts as the actor seems to split into multiple versions via pre-filmed images, each overlaid upon the other and moving jerkily in different directions, some twisting and crawling away as if lurching out of a grave. This haunting sequence, with its suggestions of death, the undead and multiple personalities, sets the tone for the production.

Importantly, it also foregrounds the production’s most significant technical detail: all the characters are played by a single actor. In a powerhouse performance, Zahra Newman plays all 23 characters, ranging from Dracula and his vampiric brides to heroine Mina Harker and the vampire hunter Van Helsing.

At first these characters are easily distinguished by rapid wig and costume changes, but as the production moves on and characters become linked in Dracula’s hypnotic control, the borders between characters become less easily distinguishable. Eventually they fall away altogether, infiltrated increasingly by the looming presence of Dracula himself. In this production, the vampire becomes less an external force from an ancient past than a monstrous potential within all of us.

As mesmerising as Newman’s flawless delivery of so many characters is, almost her equal on stage is the spectre of technology itself. While Newman is the only character on stage, she is often surrounded by crew members who follow her with film cameras, broadcasting via the screen where the images are combined seamlessly with pre-filmed scenes of Newman playing other characters.

- Life in a new language: how migrants face the challenge

- Journalling about everyday stressors could boost resilience

Film technology – the medium of communication – becomes another character on the stage; a twenty-first-century twist on the novel’s original preoccupation with communication technology. Stoker’s narrators tell their stories via journals, diaries, letters, telegrams, newspaper cuttings and early voice recordings, all transcribed via the modern technology of the typewriter. The cine-theatre approach updates this preoccupation at the same time as it uses it to foreground its focus on the mind, distorting and disrupting the boundaries between characters.

The result is an intelligent, innovative and entertaining adaptation of Stoker’s classic vampire tale. If you’re a fan of vampires, classic literature, the Gothic, or just of good quality theatre in general, this performance is one not to be missed.

Dr Kirstin Mills, pictured, is a Senior Lecturer and Director of the Master of Research in the Faculty of Arts. Her research specialises in Gothic literature and media from the nineteenth century to now.

The Sydney Theatre Company production of Dracula is on stage now until August 4.