Macquarie University palaeontologist Sally Hurst has helped uncover the first evidence of multispecies dinosaur herding from ancient footprints that were preserved in ironstone 76 million years ago.

Ancient steps: Macquarie University researcher Sally Hurst next to one of the tyrannosaur footprints from the Skyline trackway site in Canada.

The research, published in PLOS One on 24 July, documents the first ‘trackways’ ever found in Alberta, Canada’s Dinosaur Provincial Park, despite scientists studying fossils there for over a century.

These tracks may show horned ceratopsians and armoured ankylosaurs travelling together — the first evidence that different dinosaur species may have cooperated for mutual protection — while two large tyrannosaurs walked perpendicular to the herd.

The team discovered the Skyline Tracksite during an international course in July 2024 for university students to learn new field skills.

Sally Hurst, Adjunct Research Fellow in Macquarie University’s School of Natural Sciences, took part in the excavations and created a 3D model of the site.

“Occasionally we find an individual footprint of a dinosaur, but when we find consecutive footprints at a site, we call them a trackway,” Hurst says.

Co-leader of the discovery, Dr Phil Bell from the University of New England says during the field trip an unusual formation caught his eye.

“I’ve collected dinosaur bones in Dinosaur Provincial Park for nearly 20 years, but I’d never given footprints much thought,” says Dr Bell.

“I noticed a rim of rock which had the look of mud that had been squelched out between your toes, and I was immediately intrigued.”

It was incredibly exciting to be walking in the footsteps of dinosaurs 76 million years after they laid them down.

That single visible footprint rim has since expanded into a 29-square-metre excavation. The site revealed 13 ceratopsian tracks from at least five animals, one possible ankylosaurid track, and footprints from two tyrannosaurs and a small meat-eating dinosaur.

Ancient predator drama?

The footprints preserved at the Skyline site have uncovered a dramatic tale of dinosaur life. At least three different species of dinosaurs were visiting the same area, which was likely a water source along ancient meandering rivers.

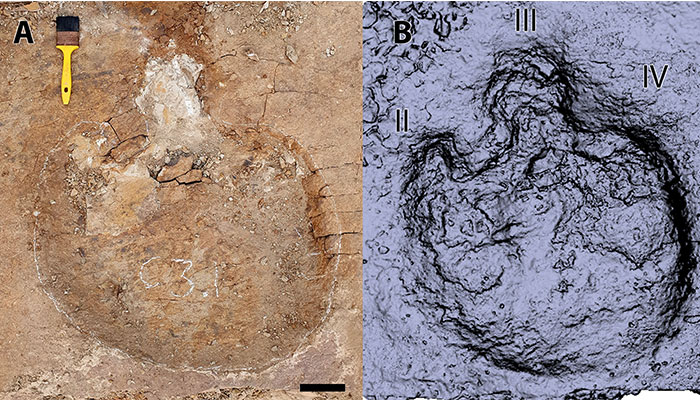

Giants walking: Ankylosaurid footprints at Skyline site. Image: Dr Brian Pickles, University of Reading.

The ceratopsian tracks show regular spacing and parallel arrangement, pointing toward the water’s edge; meanwhile the tyrannosaur tracks run parallel to the waterline, positioning that suggests these predators may have been stalking the herbivorous herd.

“The tyrannosaur tracks give the sense that they were really eyeing up the herd, which is a pretty chilling thought, but we don’t know for certain whether they actually crossed paths,” says Dr Bell.

Interpreting ancient trackways presents challenges. The footprints show these animals visited the same location, and were all preserved around the same time, perhaps in a flooding event.

But these tracks could have been made hours or even days apart. Across such vast time scales, it’s nearly impossible to determine if the tracks were made simultaneously.

New search methods

The discovery has transformed how researchers hunt for dinosaur tracks, as Dr Bell’s initial finding helped researchers recognise protruding sediment displacement rims previously overlooked. These iron-rich features, when excavated, revealed complete trackways.

“It was incredibly exciting to be walking in the footsteps of dinosaurs 76 million years after they laid them down,” says Dr Brian Pickles from the University of Reading, field course organiser and co-lead author of the research.

“Using the new search images for these footprints, we have been able to discover several more tracksites within the varied terrain of the Park, which I am sure will tell us even more about how these fascinating creatures interacted with each other and behaved in their natural environment.”

The multispecies herding is similar to modern African ecosystems, where different herbivore species travel together for protection against shared predators.

“Like zebras and wildebeest in Africa today travel together for safety in numbers, these dinosaurs could have been doing the exact same thing, with large tyrannosaur predators in the vicinity,” says Hurst.

Trackway tales

Hurst says the Canadian discovery has parallels with Australia’s famous Lark Quarry track site in Queensland, where 95 million years ago a large predator also stalked smaller dinosaurs at a water source, resulting in what has previously been interpreted as a chaotic stampede of 150 terrified dinosaurs fleeing a charging theropod.

However the new find also suggests multispecies cooperation among herbivores travelling together for protection.

Hurst says most dinosaur excavations involve bones and skeletons which don’t show evidence of interactions between dinosaurs, unless perhaps a bone has a bite mark from a predator.

“Trackways occur while the animals were alive, and whether they were grazing or looking for water or travelling and migrating, it’s very exciting to see a rare glimpse of these behaviours preserved from when they were living animals,” she says.

“Many people think that we’ve dug all of the dinosaurs up, and that we’re just studying the same material - but finds like this show that there are new discoveries waiting to be unearthed. Each new find helps us to learn more, piecing together the puzzle of the past, and telling us new stories of the animals and environments that came before us.”

Sally Hurst is an Adjunct Research Fellow in Macquarie University's School of Natural Sciences and creator of the Found a Fossil Project.