State and federal politics has always been a dance of diplomacy. Yes, it is about power and identity, but it is also proprietorial. There is nothing like a border dispute to bring on a little state-level pride.

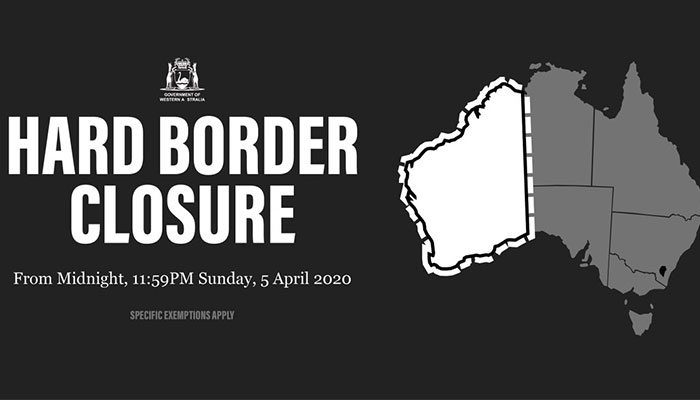

Initially, COVID-19 saw the states coming together in a way that hadn’t been seen since the outbreak of Spanish flu led to brief closures of several state borders a century ago, the only other instance since federation enshrined the states and territories. Apart from the odd mixed message over schools, Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s national cabinet of state and territory leaders delivered a united front in its response to the pandemic.

But as the health crisis abates and the curve flattens, the way forward has become more about the economy, the tourism dollar, and the expectation of returning to free movement across state borders for Australia’s citizens.

While health authorities have said there is no real reason for closures to remain, the governments of Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania are maintaining their border restrictions. High Court challenges have been mounted and premiers are struggling to justify the closures any further, and we are seeing that playing out in the debate.

Our imaginary friends

The existence of borders is all very much part of an 'imagined community', where we start identifying as the nation we come from, as if everyone from that nation has principles that tie them together in a way that can be neatly contained within a border. Lately, we’ve been seeing this at the state level.

Australian communities are highly connected and rely on border crossing movements for visiting family, schooling, work, shopping, and access to health care.

With the idea of the imagined community comes the notion of borders as something we can very easily close and seal off. Nationally, yes, decisions are made about who comes and goes into Australia, but for state borders the constitution generally prevents exclusion. This is the point now likely being challenged in the High Court (i.e. is the pandemic reason enough to prevent free movement).

Borders are intended to function more as a filter. No matter how perfect we think our systems are and how stringent our controls, our borders necessarily remain porous.

Border towns divided

Like the twin cities of Nogales, Sonora (Mexico) and Nogales, Arizona (US) that are divided by the international border, where I lived and researched for several years, Australian communities are highly connected and rely on border crossing movements for visiting family, schooling, work, shopping, and access to health care.

Standstill: traffic chaos at the border of NSW and Queensland during the covid crisis March 2020. Image credit: whichcar.com.au

The perception that you can just close a border does not sit well with those who live within these border communities.

- A new way of life: the great substitution effect of 2020

- Talking the talk: new games help kids learn to speak

Tweed Heads and Coolangatta, for example, are highly integrated communities with multiple points of entry. Broken Hill, too, is a key example. The town is in remote western NSW but geographically (and mentally) closer to Adelaide, which relies upon necessary services elsewhere in South Australia. Similarly, remote towns in western NSW often send their children to boarding schools in Adelaide.

The current spat between states is a reminder that although Australia is an island and that we might think we are part of a borderless world, we actually live with multiple borders.

These take the form of onshore and offshore detention of asylum seekers, airports, sea ports, state borders, islands used for quarantine purposes, and maritime borders. Following a long-running dispute, in 2018, Australia and East Timor signed a historic treaty on a permanent maritime border in the Timor Sea that delivered to East Timor revenue from oil and gas reserves.

Why our borders are where they are

While Henry Parkes is known as the father of federation, those who did the actual physical legwork of federation were the surveyors who spent years drawing up the state boundaries in remote, harsh terrain, in dispiriting heat and with instruments sometimes unfit for the task.

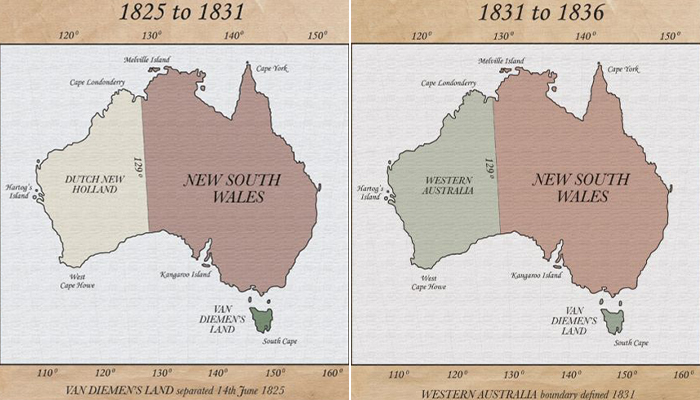

In the beginning: everything west of a vast tract of Australia known as NSW was once called Dutch New Holland. Image credit: heritageaustralia.com.au

Most of our state borders are based on geography (mountains and rivers were often used) but also simple latitude and meridians. In some instances, such as for the ACT, watersheds, in particular, have been used to determine boundaries, as were existing settlements.

Western Australia has made several attempts to secede from the rest of the country. Most notable was the failed 1933 referendum, which voted in favour.

Like the delimitation and demarcation of international borders, our state borders were based on a mix of geography, politics, and demographics. Borders, while relying on natural elements, are anything but. They are social and political imaginaries imposed on the land, and often upon communities, that remain open to dispute and redrawing.

Ultimately, it is important to remember that borders are also commonly forms of colonial practice. Australia’s state (and national) borders were imposed without consideration of indigenous communities, or indigenous understandings of natural environments. As Macquarie Emeritus Professor Richie Howitt reminds us:

“On the one hand, the colonial project sought to empty landscapes of unwanted elements: trees were cleared; rivers dammed; and indigenous populations slaughtered and contained. On the other hand, the landscapes were filled with new elements: new property titles; new pastoral and agricultural species; new people. Geography was directly implicated in that project.”

In a cartographer’s nutshell: In 1786 what we now know as Australia was halved along the 135⁰ meridian, NSW east of it, New Holland west. In 1825, NSW swiped left by six degrees. New Holland became Western Australia in 1829 after Captain James Stirling took formal possession by proclamation having sailed up the Swan River, thus preventing any French or Dutch annexation of the western part of the continent.

By 1826 Tasmania was being depicted as separate from the mainland. On the big map, South Australia rented a room from NSW in 1836 and Victoria came into being in 1857. Queensland took the top half of NSW in 1859, and what would become the Northern Territory in 1863 was a kind of NSW outpost prior to that in 1861.

Has the federal-state system run its course?

Dispute inevitably comes with territory. The land borders of Victoria with NSW and South Australia have historically generated more litigation than any other state borders.

How the west was won: New Holland became Western Australia in 1829 after Captain James Stirling took formal possession by proclamation having sailed up the Swan River, thus preventing any French or Dutch annexation of the western part of the continent.

Part of the NSW border with Victoria is the Murray River. But was the border to be the centre of the river, the north bank or the south bank? What would happen if the river changed course? Eventually it was settled that the southern bank would be the border, placing the waters of the Murray within NSW.

Western Australia has made several attempts to secede from the rest of the country. Most notable was the failed 1933 referendum, which voted in favour (68 per cent), but was refused by the United Kingdom House of Commons after a delegation travelled to London.

Iron ore magnate Lang Hancock founded the Westralian Secession Movement in 1974 in protest over taxes and tariffs. Behind this effort, and others since then, is the perception that resource-rich WA’s contribution to the national economy is disproportionate.

There is recognition that some of our borders were not perfectly set given the myriad complexities and considerations that surround them, while future disputes are not out of the question.

While Covid-19 and events such as the summer bushfires highlight issues around resources, funding and questions around jurisdictions, I don’t believe the federal-state system has run its course. The last two months have shown the importance of that coalition of voices, the importance of having a connection to the communities local and state governments serve.

We must remain aware, however, of the risks that ‘border thinking’ brings.

Dr Andrew Burridge is a Lecturer in Human Geography in the Department of Geography and Planning. His new unit Borderless Worlds (GEOP3060) will be taught from Semester 2 2020. He convenes the interdisciplinary Refugee Studies major (Faculty of Arts) – unique to Australia – offered by Macquarie University.