What is a referendum?

A referendum is a vote on a proposal where voters are asked for a simple Yes or No answer. In Australia it is the mechanism by which the Constitution can be altered.

In most parts of the world referendums have been held on a range of issues that may or may not have constitutional implications, from Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, to New Zealand’s referendums on changing the national flag, or on cannabis legalisation or tax rates in some states in the USA.

For a referendum to pass, the proposition must gain a ‘double majority’, in other words, a majority of votes overall as well as a majority of states (four out of six; the territories are only counted in the overall vote).

What’s the success rate?

Forty-four referendums have been put to the Australian people and eight have been successful, the last of these was in 1977 when three out of four questions were passed. The last referendum, on the Republic, was in 1999.

What did we say “yes” to?

Most of the successful referendums have concerned uncontroversial questions often of a procedural nature, such as the replacement of Senate casual vacancies or the retirement age of High Court judges (both in 1977).

The highest Yes vote (90.77%) was the 1967 referendum which enabled the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as well as to include them in the Census. There was a broad agreement on the need to address Aboriginal disadvantage.

Forty-four referendums have been put to the Australian people and eight have been successful.

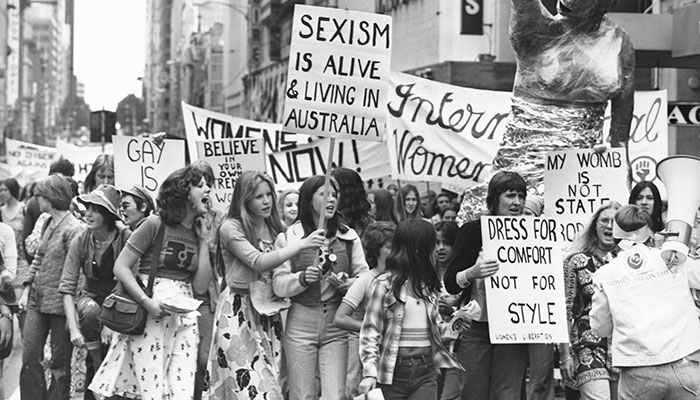

The most controversial referendum?

In 1951, at the height of the Cold War, the Menzies government backed a proposal to enable the parliament to ban the Communist party. It was a bitter campaign that resulted in a very close vote; the states were split, three in favour and three against, and the overall vote was close to 50/50.

How did the idea of referendums come about?

One country that has a well-established tradition of referendums is Switzerland which has been using them since the 16th century. With the coming of modern democracy in the 19th century they were employed more widely. The Australian Constitution itself was ratified through referendums in the 1890s. It is perhaps not surprising that this became the means chosen for changing the Constitution.

In what way are postal surveys and plebiscites different from a referendum?

In Australia a referendum refers specifically to a vote to change the Constitution. It is also legally binding. If the majority of people in a majority of states vote Yes then the Constitution must be altered accordingly.

Plebiscites and postal surveys are not legally binding but have an advisory function. There have only been three plebiscites at a national level in Australia - in 1916 and 1917 on the question of conscription, and then in 1977 on the national anthem.

There have been plebiscites at state level on questions including Sunday trading hours, pub closing times and daylight-saving times.

The postal survey on same-sex marriage in 2017 was the first of its kind, though the plebiscite on the national anthem in 1977 was preceded a few years earlier by a telephone poll to gauge support for a change. Unlike referendums, voting is not compulsory in postal surveys.

How important is the wording of a referendum question?

The wording is crucial, as the outcome of the 1999 referendum on whether Australia should become a republic showed. Polls then (and now) have shown broad support for the republic; however, much of this support is quite soft, and there is disagreement among republicans about the best model.

In 1999, the republican cause was divided between those who favoured a modified version of the current arrangement that would have seen the parliament choose a President versus those who favoured a Head of State directly elected by the Australian people.

Many republicans now say there should be two separate votes – one on whether or not to become a republic and another on the model. The counter argument, of course, is that Australians shouldn’t be asked to vote on an arrangement that is unknown.

What is the Voice seeking?

It will be an advisory body representing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a body able to make representations to the parliament and the executive government on matters relating to ATSI people. Beyond this, much of the detail is yet to be worked out though there are various documents (such as the report written by Marcia Langton and Tom Calma) which give some idea of how it might function.

Why is the wording of the Voice proposal so contentious?

The government and its advisory body want to keep the wording as general as possible and leave it to parliament to decide the detail on the functioning and composition of the body.

Some are pushing for more detail to be released on the grounds that too much is left open. Sometimes the motivation for this opposition is a deliberate attempt to create confusion. But it could also be argued that confusion arises when insufficient information is provided, and thus far the government has been cagey about engaging in debates over the detail.

Who decides what words are used?

Ultimately it is the government that decides on the exact wording, but they have consistently backed the form of words devised by the Referendum Working Group.

The wording has recently been considered by a parliamentary committee, but as the government holds the majority on the committee there has not been any change to the wording.

Of particular concern for some is the wording regarding the scope of the Voice. Should it be a body that can make representations to parliament as well as the executive? The working group and the government insist it must be both.

Do we have to vote?

Yes, voting in a referendum is compulsory.

Ian Tregenza is an Associate Professor, teaching Politics and International Relations in the Macquarie University School of Social Sciences.