Virgil wrote The Aeneid over a period of a decade (29-19 BCE) in the reign of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, (27 BCE-14 CE). The poem begins with the fall of Troy, captured by the Greeks, and then traces the journey of Trojan prince Aeneas’ journey with his father and son to Italy.

Aeneas meets with Dido, the Queen of Carthage, in Book IV of The Aeneid. It’s a pivotal moment. Will Aeneas remain in Carthage in love with Dido? Or leave to take the Trojans to Italy – leading to the founding of the city of Rome (753 BCE).

Of course, he left Dido and Rome was founded – the city that later famously destroyed Carthage (146 BCE). Tragically, Dido, abandoned, took her own life.

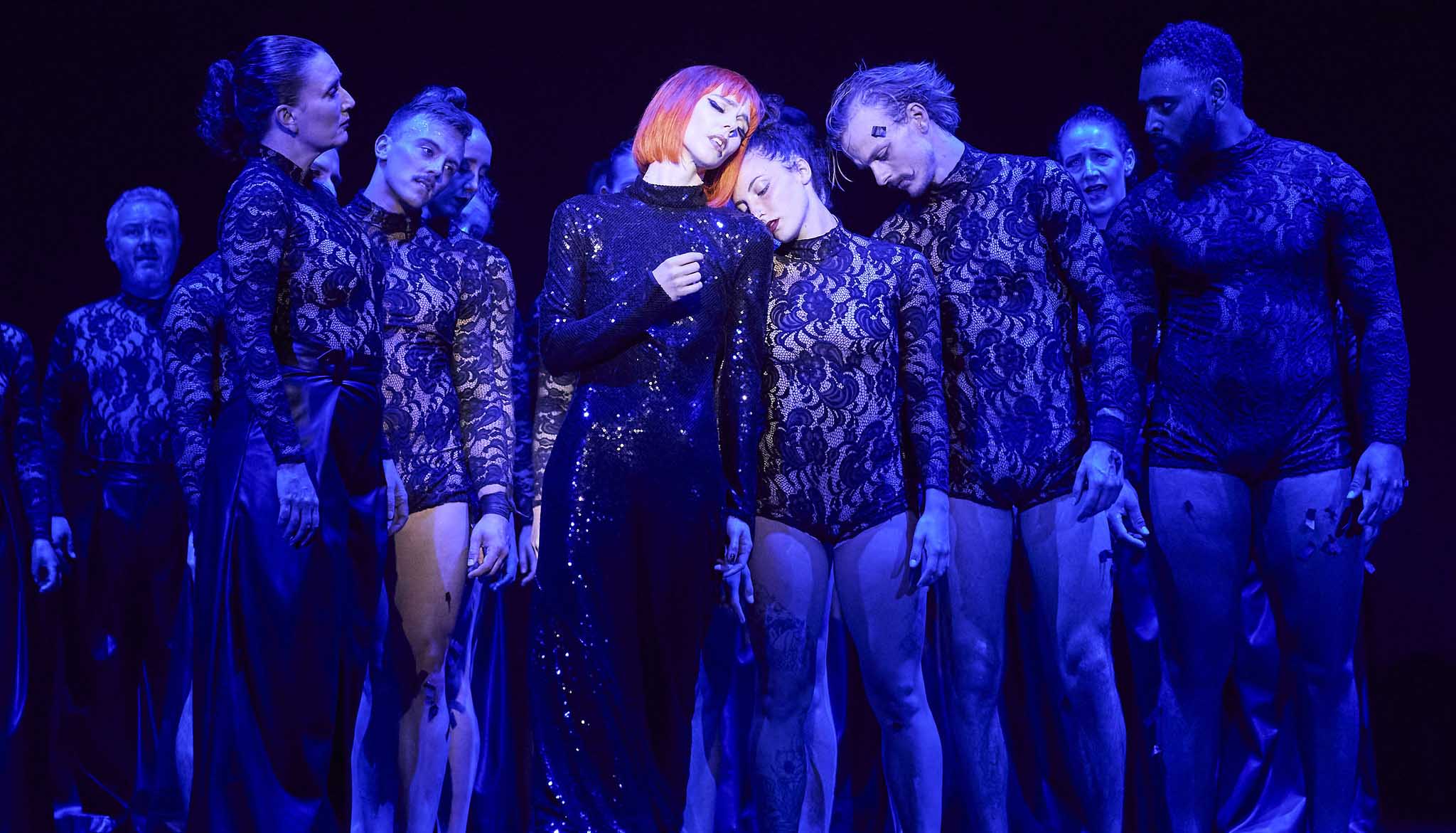

Bringing to life the epic tale of Dido & Aeneas: Nicholas Jones as Aeneas, Anna Dowsley as Dido and the Circa Ensemble. Image credit: Keith Saunders

This mythical tale is older than Virgil himself and probably goes back to the 6th century BCE, but it was Virgil who made the story famous and that in turn caused the story to be picked by the English composer Henry Purcell (1659-1695) for the creation of his opera Dido and Aeneas in the 17th century. It is Purcell’s most famous opera, with its libretto, or text, written by Nahum Tate (1652-1715).

Presented by Opera Australia and now playing at the Sydney Opera House’s Joan Sutherland Theatre, Opera Queensland’s unique rendition fuses beautiful musical performances with physical feats better associated with the circus.

Renowned Australian performing arts company Circa can be credited with the acrobatics, while the vocal talents of mezzo soprano Anna Dowsley (Dido/Sorceress), tenor Nicholas Jones (Aeneas) and soprano Jane Ede (Belinda) shine across the 80-minute production.

A richness of costume and text projection provide further depth to the show. The projections depict key themes – love, honour, fate – as well as lyrics from the libretto, including ‘I sing of arms and of a man' – the famous opening line of The Aeneid.

Acrobatics add an exciting visual spectacle to the opera. Credit Keith Saunders

There are also other, more recent, pop culture texts such as the lyrics from the 1980s hit song A Total Eclipse of the Heart. There is much to surprise even in the words simply projected above the stage.

This may all sound wild and innovative, but if we look to history and the first performances of Dido and Aeneas, we can identify how this work was designed for exactly this type of interpretation.

The earliest known performances of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas involved dancers from Josias Priest’s Girls School in Chelsea, circa 1689. This explains the prominence of female characters – it was designed for gentlewomen to demonstrate their dance moves, a relatively new form of performance at the time. Priest was a dancing master and choreographer who had set up the school. There are 17 dance sequences that integrate acrobatics into the performance at the Sydney Opera House.

A 17th-century painting of The Death of Queen Dido. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Tate’s libretto does not slavishly follow The Aeneid – rather, it is truly a 17th-century adaptation. This was a century that featured notorious witch trials in England and America. The 1680s also saw the abdication of monarch James II, a convert to Catholicism who was replaced in England by the joint rule of the Protestant couple William of Orange and James II’s daughter, Mary.

Thus, in Act 1of the opera, we are firmly with The Aeneid in the court of Dido, but in Act 2 we are far removed from Virgil and the ancient world, in a cave with a sorceress, plotting the demise of Dido and the departure of Aeneas. That departure can be linked back to the abdication of James II and his conversion to Catholicism – Puritans saw Catholicism and witchcraft as equivalents in the 17th century.

The end of Purcell’s opera also deviates from The Aeneid. Act 3 is set at the harbour and the palace of Dido, but there is a 17th-century twist here as well. Virgil’s original theme of a virtuous Aeneas abandoning Dido is replaced with Aeneas as a romantic hero leaving Carthage at Dido’s insistence.

He’s lost in love: “In spite of Jove’s commands I’ll stay. Offend the gods, and love obey."

Dido insists he leaves. The conclusion, with Dido abandoned and broken by love articulated through the closing aria ‘When I am laid in earth’, creates a sense of frenzy reminiscent of Virgil’s epic poem.

A modern representation of this mythical tale. Credit Keith Saunders

There were other adaptations of The Aeneid for opera in the 17th century, such as Francesco Cavalli’s Didone, performed for the first time in 1640, but this depiction featured considerably more male voices than those in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, which was written and designed to engage with the latest 17th-century trends of female dance.

Just as dance was a new genre of performance combining with another new genre, opera, in the 17th century, today circus combines with opera as a 21st-century equivalent and, thus, can be seen to be very appropriate for this epic tale.

Dido & Aeneas is performed at the Sydney Opera House until March 29.