Australia’s workforce has been upended by COVID-19 with the number of unemployed hitting a five-year high, and the underemployment rate also increasing dramatically.

Dramatic rise: The number of unemployed people jumped by 104,500 to 823,300 people at the height of the pandemic between March and April, 2020, the largest number of people out of work since September 1994.

The catastrophic numbers not only underscore the significant dislocation to the workforce in recent months, but also highlight the structural differences that exist among the unemployed in today’s society.

Fearsome threesome

An individual who is willing and actively seeking work but who cannot find a job is deemed ‘unemployed’. However, an individual may be unemployed due to three distinct reasons: structural, frictional and cyclical.

For example, if unemployed information technology workers at Qantas are unable to find IT work, then they are structurally unemployed due to a mismatch of skills. Whereas an unemployed Qantas baggage handler looking for a job at supermarkets for home deliveries is deemed as frictionally unemployed while they look for, or switch between, jobs.

As the economy recovers during these uncertain times some businesses are likely to hire workers only on a casual or part-time basis.

And the overall economic downturn due to COVID-19 that creates a lack of demand delivers cyclical unemployment.

Unlike previous economic downturns, the current cyclical unemployment is caused by a forced coma, and not a correction or the bursting of a bubble.

The April unemployment figure of 6.2 per cent, compared to 5.2 per cent in March, is impacted by all three reasons. It is worth noting that people on the JobKeeper scheme, even if they are not working or have been stood down, are still counted as employed which has kept the jobless rate number down. The number of unemployed jumped by 104,500 to 823,300 people, whereas employment decreased by almost 600,000 which could be a sign of discouraged workers not actively seeking work.

It is impossible to match the skills, location and transition time of every labour force participant out of work with an available job. In this pandemic, individuals have lost jobs in the hospitality sector, while hiring in the retail grocery sector has boomed (structural unemployment).

Some industries that have adopted automation and other technology-centric solutions that require fewer workers are further contributing to structural unemployment.

In this climate, as always, it will take time to transition between jobs (frictional unemployment).

As the economy recovers during these uncertain times some businesses are likely to hire workers only on a casual or part-time basis. This contributes to underemployment – where workers would like to work more hours but are unable do so.

Significantly underemployment was reported at 13.7 per cent for April, compared to 8.8 per cent in March, which demonstrates that many Australians are not working at their full capacity.

The participation rate decreased to 63.5 per cent from 66.0 per cent as a result of workers dropping out of the labour force as they are discouraged from looking for employment.

Policy responses

The traditional actions of lowering interest rates (monetary policy), cutting taxes and increasing government spending (fiscal policy) could drive cyclical unemployment to zero. But right now, there are grave uncertainties leading to less business confidence and people worried about job security and affordability.

Lessons: investment in education, training and technology will equip workers with skills that transfer easily across industries, say De Mello and Karunaratne.

We might see some success here with a demand-driven recovery; however, the persistent structural and frictional issues mean that some unemployment will always exist – this is known as ‘the natural rate of unemployment’.

For the long term, the pandemic necessitates a switch from macroeconomic policies to microeconomic policies (microeconomic reform) towards unemployment.

Investment in education, training and technology will equip the labour force to be more agile and easily move across jobs and industries – via transferable skills and a diversified skill base. Providing grants and subsidies to schools for adopting cutting-edge learning technologies and teaching the transferable skills of the future would be one avenue to explore.

This virus has reset the world’s thinking in many ways. One sector the government may need to focus on is manufacturing.

Authorities could also invest in using best-practice engagement platforms to connect remote communities so that the labour force is equipped with new skills. Australia’s workforce needs to be dynamic and ‘elastic’ to succeed in an ever-evolving global economy in order to withstand periodical shocks.

The allocation of public funds to education and technology might be a better option than further fiscal stimulus to other parts of the economy. It is only through skill diversity and agility of the workforce that Australia will have real economic activity creating GDP, rather than using public funds to save industries that fail to be agile and adapt.

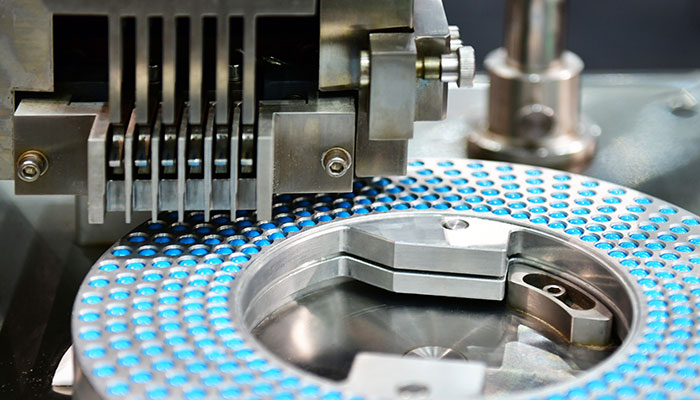

This virus has reset the world’s thinking in many ways. One sector the government may need to focus on is manufacturing. An improved incentive structure could be put in place to encourage more domestic production, particularly in high value-add manufacturing where Australia has a comparative advantage, such as medicine.

Remedy? Incentives to increase manufacturing such as pill production is one possible high value-add solution to unemployment woes, say De Mello and Karunaratne.

An optimistic 12-month outlook might be driving stock markets right now, but it’s business confidence and the ability to adjust to a new world order that will determine how well Australia awakes from this coma.

Dr Lurion De Mello is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Applied Finance at the Macquarie Business School.

Dr Prashan Karunaratne is a Lecturer in the Department of Actuarial Studies and Business Analytics at the Macquarie Business School.