Researchers at Macquarie University have found a significant portion of shark meat sold in Australian fish markets and takeaway shops is mislabelled, and includes several threatened species.

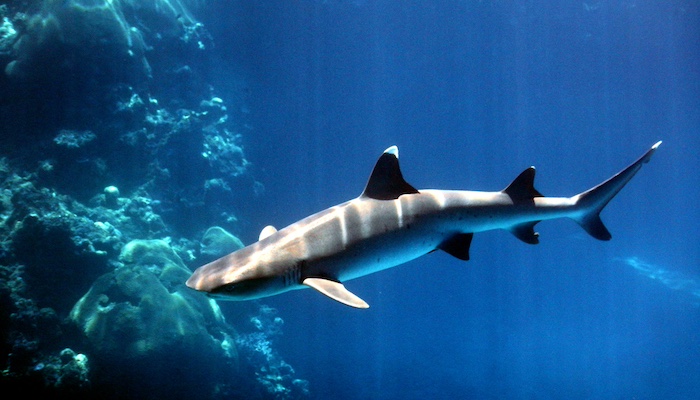

Threatened species: Vulnerable, threatened and endangered shark species such as this white-tip reef shark are falsely sold as 'flake.' Credit: NOAA, Creative commons 2.0

The findings, published in the journal Marine and Freshwater Research this month, highlight the ineffectiveness of seafood labelling and the grave implications for both consumer choice and shark conservation.

Research carried out by Master of Research candidate Teagan Parker Kielniacz, and supervised by Nicolette Armansin and Professor Adam Stow, collected 91 samples of shark meat from 28 retailers across six Australian states and territories.

Using DNA barcoding, a technique that matches genetic sequences to a reference database, they identified the species of each sample and compared it with the label applied by the retailer.

High level of mislabelling

The results of the study were alarming. Around 70 per cent of the samples were mislabelled, either because the species did not match the label or the label did not comply with the Australian Fish Names Standard (AFNS).

Mislabelling was particularly high for samples labelled as 'flake', which the AFNS restricts to fish from just two sustainably caught shark species: the gummy shark Mustelus antarcticus and New Zealand rig shark M lenticulatus.

The research found that 88 per cent of 'flake’ samples were from neither of these species.

“Our research shows that mislabelling of shark meat is a widespread problem in Australia,” said Ms Parker Kielniacz.

“Consumers assume that because you can buy flake, it is a sustainable choice, but it's a bit more nuanced than that; most flake was not from sustainably caught shark species.”

The study identified that nine of the samples came from three species listed as threatened in Australia, including the critically endangered scalloped hammerhead and school shark. All were sold as ‘flake’.

Ms Parker Kielniacz says mislabelling was markedly higher in takeaway shops compared with fish markets and wholesalers, indicating the problem worsens down the supply chain.

“I was surprised by the amount of people who didn't know what flake was. They didn’t realise it was shark, or even know that shark could be sold,” she says.

Setting a baseline

The research underscores the urgent need for improved labelling standards and enforcement, says co-author and research supervisor Ms Armansin.

“Many shark populations are facing unprecedented declines worldwide, and yet consumers have little idea of the provenance of the fish they are eating, and they are not told they are eating a threatened species,” she says.

Our study found that for 70 per cent of samples, we're not getting what's on the label – that's really significant.

While Australia is signatory to several relevant international conventions, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1995 United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) on sustainable fisheries, the use of Australian Fish Names Standards is only a recommendation.

“As long as Australia allows shark meat to be sold just as 'shark meat', we can't enforce labelling standards, which is a problem for both consumers and for threatened species protection,” says Ms Armansin.

“Without having a baseline that says this is what you need to tell consumers, there's nothing to say you're doing it poorly.

“Until labelling laws are taken more seriously for seafood in general, we're chasing our tails because there's no standard.”

Mislabelling shark meat is a global problem, she adds.

“Ambiguous trade labels like ‘flake’ are a real hindrance to sustainable consumption.”

Misleading: 70 per cent of the samples collected for the study were not labelled correctly.

Mass DNA testing

Professor Stow heads the conservation genetics laboratory at Macquarie University, where this research was conducted, and is the corresponding author on the study.

He says DNA testing is rapidly becoming cheap, flexible and fast enough to enable large-scale monitoring of the seafood supply chain.

“DNA barcoding is becoming an efficient and tractable way to monitor species of origin when it comes to fish, and in particular, sharks,” he says.

Rapid screening methods, such as testing bilge water from fishing boats or wastewater from fish markets, could be used to determine what species have been caught or traded.

“It’s possible to collect a sample from drains next to a fish stall to identify exactly what species are being sold in that market and flag any endangered species,” Professor Stow says.

“One way forward is to industrialise cheap and efficient means of large-scale DNA monitoring.”

This study shows that giving consumers access to accurate information is vital for building a more ethical and sustainable shark meat industry in Australia.

“Everybody wants to trust that what they're eating is what the label says it is,” Ms Parker Kielniacz says.

“Our study found that for 70 per cent of samples, we're not getting what's on the label – that's really significant.”