Trust is important for societies, markets and democracies to function properly. Recent indiscretions and missteps by two of our key social institutions – government and business – are raising questions about dependability and trust by an increasingly cynical public.

Scandal: Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate has resigned after being criticised for giving Cartier watches to four senior managers.

One survey found that trust in our political institutions and politicians is once again at record lows.

This is hardly surprising as political scandals abound, such as the one engulfing NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian and the ICAC investigation into whether former MP Daryl Maguire used his political position for financial gain, which seems to reinforce this trend.

There seems to be a similar loss of trust in business too, especially in the financial services industry and the aged care sector following recent royal commissions.

Political and business leaders are, overall, probably not significantly morally better or worse than the rest of us.

We have also just heard about Crown Resorts’ failure when it came to tackling money laundering and links between organised crime and junket tour operators at the NSW Independent Liquor and Gaming Authority inquiry.

Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate has been criticised for giving Cartier watches worth a total of $20,000 as a bonus to four senior managers. She has since resigned. That scandal, along with the expenses issue involving the top two executives at the corporate cop, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission, has drawn fire from both sides of the political fence.

We see similar mistrust of large technology companies, such as Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon, who are being investigated for misusing their market power to engage in anti-competitive behaviour.

There are also concerns about their invasions of our privacy, their manipulation of us to sell advertising, and the ability of their platforms to fuel conspiracy theories and fake news that may undermine our democracies.

It is not hard to see why there might be an emerging crisis of trust in government and business.

Three facets of trust

Philosophers often describe trust as having three components: vulnerability to harm, competence and willingness.

Controversy: An inquiry exposed Crown Resorts' failure when it came to tackling money laundering.

For example, when I trust that you will perform your official duties with honesty, I make myself vulnerable to harm if you fail to do so, I rely on you having the competence to fulfill your duties, and I assume your willingness to do so honestly.

Conversely, a lack of trust means that I will try to limit any harm that I might face because I do not rely on you to be willing or competent to act honestly in conducting your official duties.

Given repeated instances of misconduct and lies both in government and business, a general weariness to trust is not surprising. But why do people and institutions act in unethical and untrustworthy ways and what can we do about it?

Ethical expertise

Ethical expertise can be understood as having four components: sensitivity (recognising a moral issue), judgment (working out what morality requires), focus (prioritising morality over self-interest and other non-moral interests), and action (actually doing the right thing).

Often the focus after political or business scandals is on a so-called 'failure of judgment', but moral failings can occur across all four components.

Failures of moral sensitivity occur when we are 'morally blind' to the moral issues that we face.

Politicians, like the rest of us, can simply keep inconvenient moral issues out of focus, or even if they may be aware at some level that unethical or illegal conduct might be occurring, they can deliberately ensure that they never find out for certain.

Finally, failures of moral action occur when, even though we want to do the right thing, we are unable to do it.

Failures of moral focus are also very common. This occurs when we prioritise our own self-interest at the expense of doing the right thing. Of course, most of us do not do this openly.

Instead, we engage in self-deception, rationalising and compartmentalising to keep from disturbing our 'self-schema' as basically a good person. The techniques of moral evasion used to achieve this are probably all too familiar to us.

- Raw deal for workplace minorities amplified by COVID-19

- The best shows on TV you are not yet watching

They include thoughts such as "I can’t do anything”, “Others would do the same”, and “The problem is too big”, as well as techniques for distancing ourselves emotionally and cognitively from the issue, such as simply not thinking about it or reaching for implausible justifications.

Finally, failures of moral action occur when, even though we want to do the right thing, we are unable to do it.

Climate change is an important example of this, because even though many political and business leaders, along with the broader public, recognise that we need to take strong action now to address it, the moral skills of leadership, persuasion and commitment that are needed to achieve this outcome seem beyond our current leaders.

Radically evil

Political and business leaders are, overall, probably not significantly morally better or worse than the rest of us.

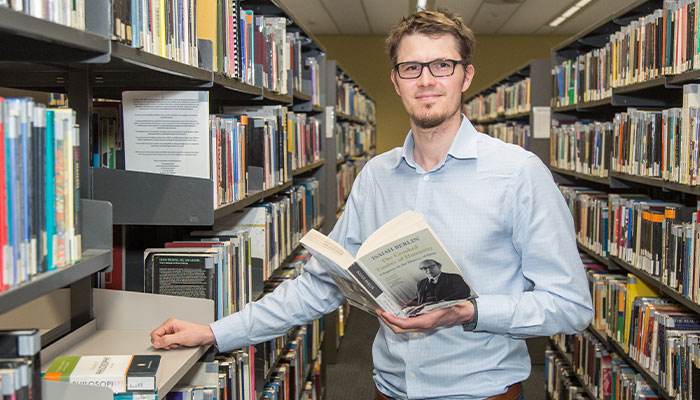

In our hands: Associate Professor Paul Formosa (pictured) says we need a public that demands and rewards better conduct from its leaders.

As the famous Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant argued, we are all 'radically evil' in that we each have a price at which we will give up on morality.

What sets political and business leaders apart from us is the power that their positions give them and the temptations to act poorly that can come with that.

- New front opens in Australia's fight to save the koalas

- Testing everyone is key to limit COVID-19 deaths

So what can we do about it? We could simply hope that our leaders will act better, but that is not likely to work very well.

Instead, we need to change the incentives at play and build better institutions, such as a federal Independent Commission Against Corruption, to ensure that unethical conduct is detected and disincentivised.

We also need a public that demands and rewards better conduct from its leaders through its actions, whether at the ballot box or the shop counter.

Dr Paul Formosa is an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy.