The tomb of Egypt’s pharaoh Tutankhamun is the whole package: the life and reign of a king erased from history and rediscovered; the incredible artefacts buried with him; the story behind the tomb’s detection and excavation.

It's in the vault: The story behind the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb continues to enthral.

Tutankhamun, nicknamed ‘The Boy King' in modern times, came to the throne in about 1336 BC, at around nine years of age. It’s believed he ruled for about 10 years. When he died, he was mummified and buried in a tomb filled with statues, jewellery, objects from daily life and other treasures chosen in order to smooth his passage to the afterlife.

The tomb, one of the smallest royal sepulchres in the Valley of the Kings, near modern Luxor, remained hidden for 3,300 years until, on November 4, 1922, the opening was discovered by a team led by English archaeologist Howard Carter (1874–1939) and his benefactor, George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon.

Golden age: The iconic death mask is one of the hundreds of items discovered in Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt.

Howard Carter discovered the tomb entrance under the tomb of King Rameses VI. Three weeks later, the tomb was opened, famously revealing “wonderful things”, he is quoted as saying.

The excavation of the tomb was a public sensation, and widely reported in the press. Some 5,000 items came to light, including a solid gold coffin, royal chariots and the pharaoh’s death mask. The tomb and its contents were exceptionally well preserved and provided Egyptologists with unique insights into the Egyptian New Kingdom of the Late Bronze Age, between the 16th and 11th centuries BC.

- Food for thought: Study finds link between depression and unhealthy diets

- Please explain: Is it possible to speed read?

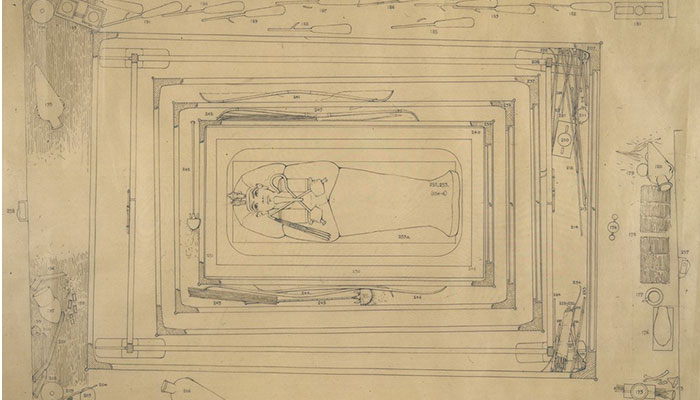

Carter was acclaimed for the meticulous way he recorded the excavation, including drawing and documenting each item and how they were constructed. The tomb took ten years to excavate, with all the original field records now held at the Griffith Institute Archive at Oxford University and fully available online.

An iconic emblem

The iconic death mask was originally found placed over the head of the mummified body of Tutankhamun. It shows him wearing the nemes – a striped headcloth adorned on the forehead with the goddesses Wadjet (the cobra) and Nekhbet (the vulture), which together are marks of Tutankhamun’s divine kingship.

The mask is an iconic emblem for modern Egypt, and a masterpiece of craftsmanship not only for the delicacy of the king’s visage mastered in gold, but for its inlays of coloured glass and semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli.

The discovery of relatively intact royal tombs is rare in archaeology, so the tomb of Tutankhamun was also a prized glimpse into the lives of ancient Egyptian rulers.

The treasures are among key exhibits in the new Grand Egyptian Museum, near the Giza Plateau, set to open soon. All up, its exhibition halls will contain tens of thousands of artefacts, including those belonging to Tutankhamun’s tomb, 2000 of them displayed for the first time.

Drawing from the past: Burial Chamber with objects in situ, Carter MSS. i.G.31. Credit: © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

The museum will be an international showpiece for Egypt's ancient cultural heritage, housing many of its most significant artefacts. It has state-of-the-art conservation labs and storage facilities enabling the optimal conditions for cultural heritage preservation.

Buried story

Before the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, the ancient Egyptians had literally erased the young king Tutankhamun from their monuments and historical texts. However, fragmentary evidence of his existence persisted.

The tomb's discovery exposed this hidden story and provided a window into one of Egypt's most controversial periods, a time beset by religious revolution led by his father, king Akhenaten and his fabled chief wife, queen Nefertiti.

The discovery of relatively intact royal tombs is rare in archaeology, so the tomb of Tutankhamun was also a prized glimpse into the lives of ancient Egyptian rulers.

Research by Macquarie academic Dr Jana Jones and her team in 2014 revealed that the origins of mummification stretch back to the fifth millennium, earlier than previously thought. Even in Egyptian prehistory, the provision of items and foodstuffs in graves indicated a desire for preservation in the next world.

As the centuries rolled on, ideas about the afterlife changed. By around 1,200 BC, a journey to the hereafter required judgement of the heart and preservation of the body, so the spirit essence of the deceased – the ba – could become an akh or “transfigured spirit” in the realm of the god, Osiris.

The gift of the Nile

The 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotus called Egypt “the gift of the Nile” and it has proved true for millennia. The advent of climate science and its application to ancient world studies enables scientists, historians and archaeologists to map long-range environmental changes to the Nile and other parts of the world.

Sign of the times: A new museum in Egypt will be an international showpiece dedicated to the country's history and heritage.

This has enabled a more holistic approach to assess societal, political and economic change and resilience in ancient times. So, for example, we can see the end of the Egyptian Pyramid Age (Old Kingdom, c. 2200 BC) as partially triggered by a wider climate event that affected political stability, food sources, and community life. There are lessons for us in this history.

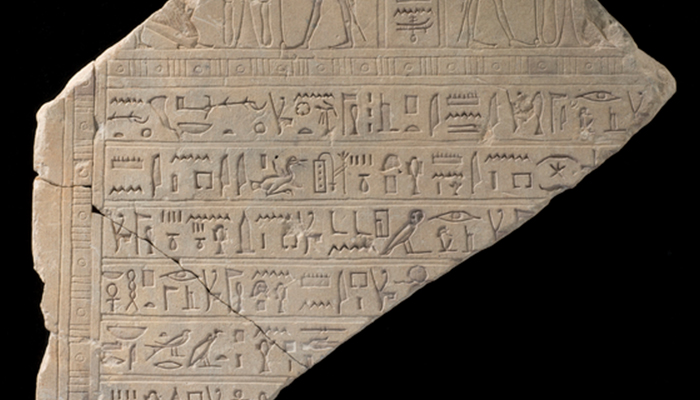

Today, Egyptology itself is also undergoing a process of self-examination. Questions include its Western origins, past colonial approaches to Egyptians and its ancient culture, and the repatriation of antiquities such as the Rosetta Stone.

Karin Sowada is an ARC Future Fellow leading the Project Pyramids, Power and the Dynamics of States in Crisis in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University. Follow her on Twitter @KS_Archaeology