Play has always been a part of who we are.

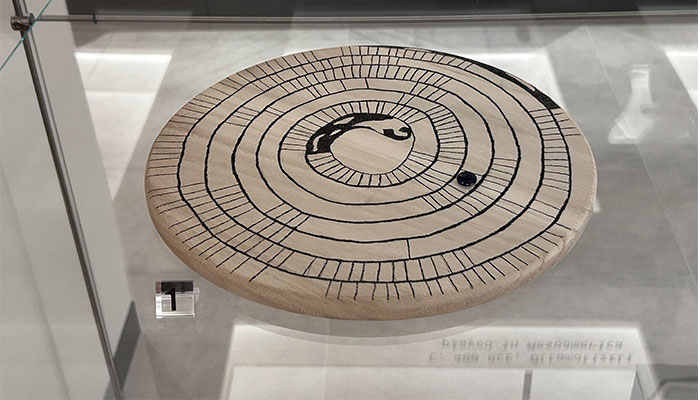

Egyptian game: This glass gaming piece was possibly used as a counter in the Ancient Egyptian game Mehen which was played with a lion-shaped piece and round counters on a board that looked like a coiled snake.

In 1949, cultural historian Johan Huizinga suggested that “Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society.”

Indeed, board games have been found in societies as far back as ancient Egypt and remain popular in the 21st century. However, the nature of play has changed.

War games, the foundation of traditional role-playing games, originated as leisure and ritual activities in pre-modern societies and often took the form of combat sports, such as pankration and wrestling.

In the Middle Ages, these combat sports coalesced into spontaneous tournaments to celebrate births, weddings, and anniversaries, or to break the boredom of a siege.

However, from the mid-1400s, the nature of wargaming shifted away from using physical weapons to tabletop gaming, aided by the popularisation of the board game chess in Western Europe. Tabletop role-play games like Dungeons & Dragons emerge from this wargaming tradition during the 20th century.

Games are often a test of skill and that is part of their appeal. Many early board games, such as Ludus Latrunculorum (roughly meaning “The Game of Mercenaries”) were about replicating military tactics and testing how good players were at strategising. Games like Mehen, a recreation of which is displayed in the exhibition, are likely less about skills that could be translated to everyday life and more about competition and strategy.

The friendly games

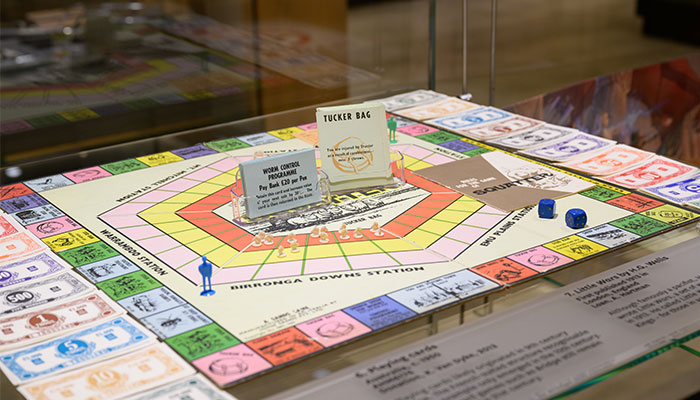

But one of a dozen reasons players still engage with and enjoy games is camaraderie. Tabletop games (board, card, and role-play) tend to be an inherently social experience. As it stands, Monopoly (a version of Elizabeth Magie’s 1904 The Landlord’s Game) is said to be the most popular board game today.

Landlord games: An Australian game of Squatter, circa 1970, where players battle drought and disease on a sheep station.

Squatter, like Monopoly, is a version of the landlord’s game. Here, players manage a sheep station and combat drought and disease.

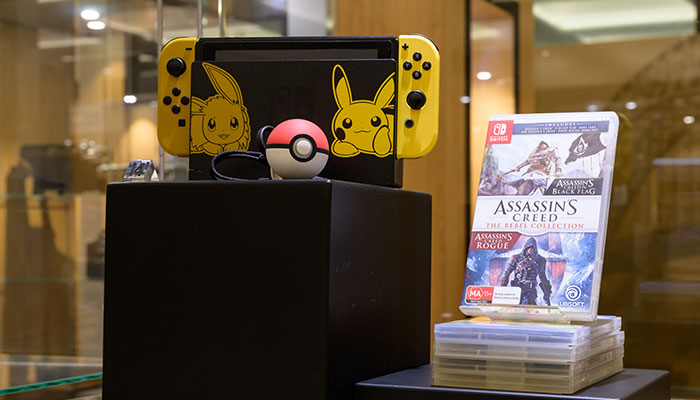

Technology has opened up a new way to game on a global scale, with 3.09 billion video game players worldwide. Technology has fundamentally shifted the way we play. For example, when Nintendo launched in 1889 they produced hanafuda, a type of Japanese playing card, but transitioned into electronic games in the 1970s, leading to the creation of many of the most well-known video game characters.

Our new exhibition, Play Through History, explores the evolution of game-playing, with objects such as glass game pieces from Egypt; ancient dice made from bone and astragalus (animal knucklebones) from the Roman Empire; modern playing cards, and contemporary gaming consoles.

One of the biggest attractions is the Nintendo 64. Like me, many visitors to the exhibition grew up playing games on this console in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It evokes a sense of nostalgia; I spent many days watching my brothers play games such as Mario Kart, Golden Eye and Banjo-Kazooie.

History in the making

The history of video games is a complex socio-cultural history and so the milestones that are important really depend on what part of gaming culture and video games you’re looking at.

Games are often thought about in terms of how players engage with them. Are they digital games, board games, tabletop games? We might see them as strategy games, and roleplay games, or examples of how the game world works, for example sandbox games, or the mechanics of the games, for example first-person shooter games.

There are several key moments that I believe are important in the history of games: the founding of the original Nintendo company in 1889, the release of “Australia's favourite board game,” Squatter, in 1962, and the 2019 release of Untitled Goose Game by Melbourne-based developer HouseHouse.

Video games are one of the most popular and profitable forms of media. Many of these games draw upon historical themes, which means that it is important for us to consider what versions of history players are receiving through their gameplay and what effects this has on their understanding of the past.

A 2021 American Historical Association study found that 11 per cent of people engage with video games to learn about history.

We know video games have the power to educate and that players learn through their interaction with history-themed games. Games are particularly good at teaching historical facts: what a building looked like, the weapons used or the biographical details of an individual, for example. What they are less good at doing is presenting nuanced accounts of social history, of demonstrating how people experienced and lived in the past.

Video games drive an obsession with history more broadly. Part of this is because they replicate history we are really familiar with, and part is because games help us to embody history.

Video games, by definition, are interactive, and so they place us in the shoes of historical actors which then allows us to act through moments in history.

The added appeal of video games is that they engage us in historical narratives, which makes history appealing to an audience that might not otherwise engage in more traditional forms of historical study.

Play Through History explores this concept, presenting three history-themed video games alongside museum objects to demonstrate how history is shaped and represented through this medium.

Play Through History is at Macquarie University History Museum until April 2025.

Abbie Hartman, pictured, is a cultural and public historian whose research focuses on how popular culture influences historical knowledge, particularly the way video games articulate and understand moments of historical trauma.

She is the author of Video Games as Public History: Archives, Empathy and Affinity (Game Studies, 2021).