New research from Macquarie University could help to slow down aggressive breast cancers, and potentially improve survival for people with hard-to-treat ‘triple negative’ tumours.

Breakthrough: Dr Heng's research could improve cancer survival for 'triple negative' patients.

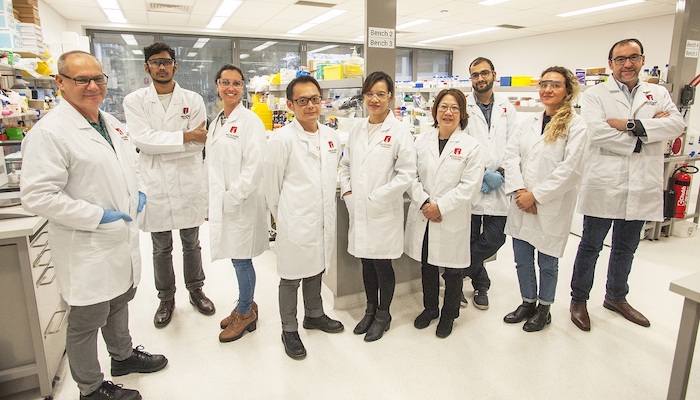

Dr Benjamin Heng is a Research Fellow in Biomedical Sciences at Macquarie University’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and is the lead author of a study published this week in the top journal in the field, Breast Cancer Research.

Dr Heng has been researching the molecular and biological activity of human breast cancer in Professor Gilles Guillemin’s research group for the past seven years, working with a cancer survivors’ advisory group to target research where it is most needed.

New immunotherapy drugs that are highly effective against other cancers, have so far been less promising in breast cancers.

“There is no single treatment that can address all breast cancers,” says Dr Benjamin Heng.

Testing breast cancer before it spreads

Early detection and surgery remain the most effective treatment, but around a third of breast cancers metastasise – where tumour cells sneak past the immune system to spread to other parts of the body, making the disease more difficult to treat.

“Our bodies naturally try to contain the tumour but we know that breast cancers use a mechanism, like an invisibility cloak, to hide from the immune system and spread,” he says.

Cancer can be very sneaky - knowing more of its secrets means we can get smarter in the way we deal with it.

Dr Heng and his colleagues are well on the way to understanding how certain tumours avoid detection – and this will lead to more effective treatment, he says.

“The next step in treatments that can complement the conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which target the cancer cells, are those that can harness our immune system to attack the cancer,” says Dr Heng.

But while these promising immunotherapy treatments have improved breast cancer survival rates, they don’t work against all types of breast cancer.

Immunotherapy escapees

Around 10 per cent of breast cancer is the subtype dubbed ‘triple negative’ because these tumours don’t rely on oestrogen, progesterone or HER2 proteins to grow, so they don’t respond to treatments that target hormones and HER2 protein receptors.

Cellular level: Professor Gilles Guillemin, pictured far right, and his team are world-leaders in molecular activity in the immune system. Dr Benjamin Heng is pictured fourth from the left.

Dr Heng says that his team has revealed that triple-negative tumours escape the body’s immune response and also get most of their energy by hijacking the kynurenine pathway, a biochemical process that occurs in human cells to metabolise certain amino acids.

The research builds on comprehensive work under Professor Gilles Guillemin on the ways that the three major breast cancer subtypes use the kynurenine pathway. It also allows researchers to identify a unique ‘signature’ for the different cancer types.

“The ability to identify subtypes of breast cancer more accurately, means we can use the most effective treatment earlier in the process,” says Dr Heng.

Understanding the secret pathway

Dr Heng says that scientists have long known that the kynurenine pathway plays an important role in the production of an essential amino acid used by the body’s immune system, tryptophan – but they didn’t know the precise role the pathway plays in the spread of cancer.

While extensive studies show that cancer patients have unusually high kynurenine pathway activity compared to healthy patients, only a limited number of studies have focused on breast cancer.

- Please explain: Can you really make friends with an octopus?

- Historical dramas: The best shows on TV you are not yet watching

“When the tumour invades a cell, it heads for this pathway and puts it into overdrive,” he says. “Then it sucks all the nutrients out, which helps the tumour grow, and it also produces multiple chemicals that kill the immune cells and let the cancer remain undetected.”

Cancer occurs when ‘multiple genetic insults’ or mutations of cell DNA cause certain cells to begin to grow uncontrollably, invading surrounding tissue, says Dr Heng.

He says that cancer cells typically keep mutating, and those that survive the treatment regime can evolve into a more resistant form.

“Learning how to evade the immune system and spread further is a trademark of cancers that evolve to a later stage,” says Dr Heng.

“Cancer can be very sneaky; knowing more of its secrets means we can get smarter in the way we deal with it.”

Dr Benjamin Heng is a Research Fellow in Department of Biomedical Sciences.