With the Reserve Bank’s interest rate already near zero, the federal government’s budget has been the main source of economic stabilisation and stimulus since the onset of the Covid-19 crisis. Appropriately, the scale of the support has been huge – with $74 billion already provided to around 5.7 million people under the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs alone.

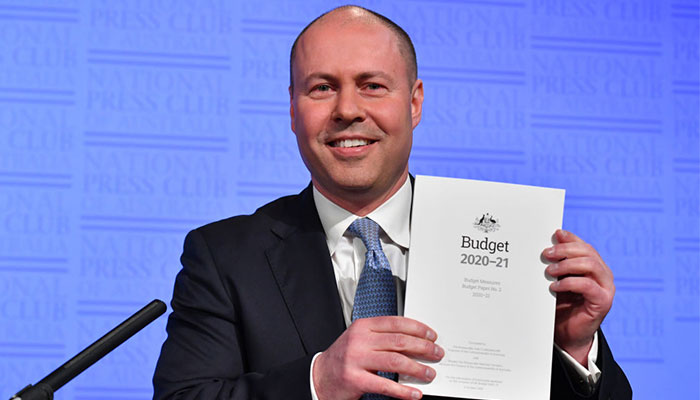

Big spender: Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg delivers a raft of tax cuts in last night's budget but Professor David Orsmond says economic pain may still be ahead.

Despite this support, the level of output still fell by 7 per cent by mid-2020, reflecting both the extensive economic shutdowns necessary to contain the virus and the pull-back in discretionary spending by households and businesses as confidence has eroded. The broad unemployment rate jumped to around 10 per cent, with youth unemployment (15-24 years) even higher.

Deep labour scarring

A recovery is now well underway. But while the effect on GDP from reopening businesses is fast, the history of economic shocks suggests it can take years for the confidence-induced drag on private spending to fully fade and up to a decade to return to pre-covid employment levels, with deep labour scarring.

On that measure, the worst could still lie ahead.

These extraordinary economic realities suggest several criteria by which to judge this budget. How will the government’s policies boost private spending in the economy; underpin a robust job recovery; and lay the groundwork for a solid pick up in productivity and economic growth to lift wages over time?

Further, given the scarce fiscal resources and rapid rise in public debt, how will the government ensure its policies provide the highest ‘bang-for-buck’ in their effect on growth, employment and on the overall debt/GDP burden?

The key to achieving that sort of rapid economic recovery will be lifting the pace of private spending and thereby output and jobs (and having a vaccine).

This budget is certainly expansive – a deficit of 11 per cent of GDP in 2020/21 (only exceeded in war years) and 10 percentage points rise in net debt/GDP (to 36 per cent). Based on a critical assumption of a widespread take-up of a vaccine next year and that border bans are ‘progressively lifted’, the recession is forecast to be short lived, with GDP rising by almost 5 per cent in 2021/22.

The budget deficit hence halves next year before trending lower; net debt/GDP stabilises at 44 per cent. Unemployment peaks at 8 per cent at end 2020 and then falls gradually, though is still 6.5 per cent by mid-2022.

The key to achieving that sort of rapid economic recovery will be lifting the pace of private spending and thereby output and jobs (and having a vaccine).

Risky business

The centrepiece of the budget strategy is to replace over the coming months the JobKeeper and (maybe) JobSeeker benefits with a two-year pull forward of the Stage 2 tax cuts, of which the main component is the increase in the top of the 32.5 per cent tax bracket from $90K to $120K and a temporary boost for low incomes.

But this is risky. While boosting overall household income, almost all the gains from the Stage 2 tax cuts will accrue to the top of the income distribution (the average wage for all employees is around $68K a year).

As widely noted, these taxpayers are more likely to spend a smaller share of any additional dollars than those at the bottom of the income distribution, who tend to be credit and income constrained and where the rise in unemployed is concentrated.

The budget adds some assistance to low-income households – extending the low and middle-income tax offset for a year and providing two $250 payments to welfare recipients – but these are temporary. And if it is left unaddressed what support will be available to those that fall between the cracks and have not secured a job when the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs are scheduled to end soon?

Subsidies and incentives

To shore up its chance of success, the budget strategy also provides a range of wage subsidies and business incentives to try to boost employment and investment. The centrepiece is a one-year, $5-10K subsidy for new hires aged less than 35 years and a grant of up to $28K for one year for 100,000 new trainees and apprentices.

There is nothing specifically focused on older workers, though history indicates they have the biggest risk of labour scarring from extended periods of unemployment. Companies with turnover of less than $5 billion can instantly write-off new investment taken by mid-2022, and many can get a refund of past tax payments to offset current loses.

Youth boost: young workers including trainees and apprentices are among the winners in last night's budget, with new-hire incentives for employers.

The key risk – again – is whether companies will take advantage of these hiring and investment incentives if concerns on the outlook continue to weigh on private sector confidence, with an associated insufficiently robust rise in household demand for their output. That does not seem secured across many industries including tourism, hospitality and entertainment, for instance.

Apart from the business tax incentives, there is little down payment on specific structural reforms to provide a more enabling environment and thereby lift productivity and economic growth.

This economic shock provides a unique opportunity to restructure the economy for the long run, including sustainable sources of energy. The rapid closure of many firms during the Covid-19 crisis to date, and the large labour and other cost savings being undertaken by those that have survived, add to the importance of new dynamic, employment-generating start-ups based around Australia’s comparative advantages.

While much of what is needed in this regard falls outside of direct budget measures – the policy recommendations in decades of reports from the Productivity Commission point to the ways forward – history shows such reforms often need budget funding to get the relevant stakeholders over the line.

Big ticket boost

More broadly, while big-ticket infrastructure projects get a further nod, along with funding for innovation in the manufacturing sector, it is open to debate whether these are the best steps to boost productivity.

Positively, the R&D tax incentives previously scheduled to be abolished have been restored, and there is extra research funding for universities and the CSIRO.

Cash splash: a $98 billion boost in stimulus measures announced in last night's budget is designed to kick-start a four-year economic recovery plan for Australia.

The 12,000 extra HELP-funded university places for2021 are welcome, given the scale of youth unemployment and the unique opportunity to lift skills and incomes over their coming 40-year careers. There is also a boost to short courses under other programs.

Australia is facing its largest economic shock since WWII and the claw back will be challenging and prolonged. Confidence was aided in the early days of this shock via the Jobkeeper and Jobseeker programs and direct cash support to business. But the current positive sentiment as businesses reopen will erode as the ongoing challenges of the future become clearer.

- Is your boss an 'avocado' leader? COVID-19's surprise bonus for workers

- Divide and conquer: why doing maths adds up to life success

At that time, a clear and consistent narrative as to how the government is moving the economy forward will be at a premium. This budget expects that using tax cuts to boost household demand and a range of business incentives to employ and invest will make a strong down payment in that direction. Time will tell.

David Orsmond , pictured, is Professor of Economics at Macquarie Business School. He previously spent over 25 years working at the Reserve Bank of Australia and the International Monetary Fund.