Tsunamis pose a rare but very serious threat to Australia, with more than 50 small tsunamis reaching the NSW coast alone since European settlement, says Macquarie University natural hazards expert Andrew Gissing.

Danger: Beaches along Australia's east coast, including Bondi Beach, were closed as the Australian Tsunami Warning System kicked in following the undersea volcano eruption near Tonga.

There are about 8000 kilometres of active tectonic plate boundaries – called subduction zones - around Australian waters, and any of these are capable of generating a tsunami that could hit our coastlines in about two to four hours, he says.

“Only about five per cent of the tsunamis generated globally are from volcanoes; the vast majority are from earthquakes,” says Gissing, an Adjunct Research Fellow at Macquarie's Department of Environmental Sciences who has worked on tsunami emergency plans for the NSW, Victorian and Australian governments.

On January 16, beaches across Australia’s east coast were closed and Lord Howe Island evacuated, as the Australian Tsunami Warning System kicked in, advising marine threats to much of the east coast following the eruption of an undersea volcano near Tonga, more than 3000 kilometres across the Pacific.

Destruction: The tsunami hits Tonga on January 16. It took the lives of at least three people. Picture credit: Twitter @sakakimoana

While the tsunami caused significant property and environmental damage and loss of at least three lives in Tonga, parts of Fiji, Samoa and Vanuatu, land threats to Australia were limited to waves of around a metre hitting Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands, several hours after the volcanic eruption.

The marine threats involved sudden tidal drops and surges and unusual and strong currents along east coast shorelines ranging from Hobart in the south, to south east Queensland. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage was caused to the oyster industry.

“Tsunamis arrive as a series of waves, the larger ones appearing like walls of water – and they tend to ripple around the globe for quite a while, taking around 24-48 hours for the energy of the tsunami to dissipate across a wider basin,” says Gissing.

The work of early warning systems

Subduction zones mark potential tsunami sources where one tectonic plate can slip under another – and include the Java (Sunda) and Timor trenches to Australia’s north-west, the New Hebrides trench to our east and the Puysegur trench to the south-east.

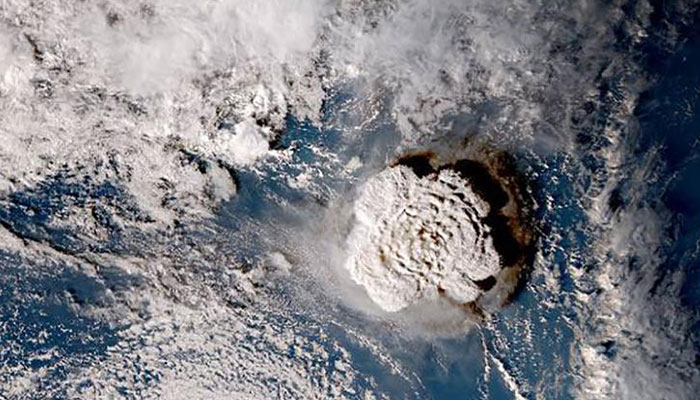

Impact: A satellite image of the undersea volcano eruption off Tonga. Picture credit: Japan Meteorological Agency

Around a third of all of the earthquakes that happen worldwide occur along these boundaries, and of the 50 small tsunamis along the NSW coast since 1788, Gissing says the biggest was probably in 1960 when a 9.5-magnitude earthquake off the coast of Chile caused unusually strong currents, tearing boats from their moorings and damaging oyster leases across the east coast.

Boxing Day 2004 saw huge tsunami waves in Indonesia and devastation around the Indian Ocean leaving more than 200,000 people dead, following an undersea earthquake measuring 9.1 in magnitude.

Tsunami from an undersea earthquake in the southwest Pacific could reach the NSW coast within two to four hours.

The deadly event prompted the establishment of the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System, NOAA in the US to expand its Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, and Australia to establish the Australian Tsunami Warning System, under the Bureau of Meteorology and Geoscience Australia.

Tsunami early warning systems involve a network of seismic instruments which detect earthquake activity, prompting analysis of the likelihood of generating tsunami waves. Deep-ocean buoys and near-shore tide gauges can also detect tsunami waves, and warnings about marine or land threats are issued to first-responders.

In Australia, this includes State Emergency Services, police, lifeguards and marine rescue.

Less than two hours to get to higher ground

“In the very rare event of a large tsunami inundating vulnerable low-lying areas of the Australian coast, it would be very challenging to evacuate large populations in a short timeframe,” Gissing says.

Threats assessed: Adjunct Research Fellow Andrew Gissing, who has worked on tsunami emergency plans for the NSW, Victorian and federal governments.

The NSW State Tsunami Plan notes that a large tsunami impacting the entire NSW coast could directly threaten between 250,000 and 1.5 million people, depending on tsunami magnitude, time of day and season.

Beaches, foreshores and water’s edge of marinas, harbours and coastal estuaries could all be at risk.

“Tsunami from an undersea earthquake in the southwest Pacific could reach the NSW coast within two to four hours, so there’s not much time to get thousands of people to higher ground,” he says.

State-wide tsunami emergency plans would kick into place, with emergency services evacuating people a kilometre away from the water’s edge and other safe areas, and automated warning texts issued to everyone in areas at risk via the national mobile phone warning system Emergency Alert.

Gissing says that if you feel a large earthquake or see water recede from the coastline, you may have just minutes before a tsunami hits. Your priority should be to get to higher ground or even up into the top floors of a very solid high building, as fast as you can.

“Large tsunami are very rare, we are talking about a worst-case scenario unlikely to happen more than once in a thousand or 2000 years on average, but because the impact would be so huge, having a plan is critical,” he says.

Andrew Gissing is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University, the General Manager of Risk Frontiers and a researcher at the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Co-operative Research Centre.