Fans of sci-fi movies such as Interstellar and Contact may not like it, but the usual ‘design’ of wormholes does not stack up, according to new research by Daniel Terno, Associate Professor, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences and Macquarie Research Centre for Quantum Engineering and Astronomy, Astrophysics and Astrophotronics.

Down the wormhole: Scientists say using a wormhole to traverse space-time is dubious.

In physics and astrophysics, wormholes are exactly what they are in science fiction. A wormhole is a structure of our four-dimensional spacetime, which is our normal three-dimensional space (height, width, depth) plus time. Einstein taught us that space (place) and time always occur together, so we should refer to this as spacetime.

Wormholes are like a shortcut through spacetime. Think of an ant on the surface of an apple. To get from one side to the other, he can crawl around the outside of the apple, or he can utilise the tunnel a friendly worm has eaten away through the middle. If the ant goes via the tunnel, he gets there faster.

A leap: In theory, wormholes allow for faster travel between different regions of spacetime.

A wormhole operates as a shortcut, too, connecting different regions of spacetime and in theory – and in sci-fi – allowing faster travel between these regions without breaking the speed-of-light barrier.

Wormholes were once a mathematical curiousity

Historically, wormholes were an almost totally ignored mathematical curiosity. They suddenly became popular in 1988 when the now-standard picture of a wormhole in spacetime was produced by American theoretical physicist, Kip Thorn.

In the spotlight: wormholes have been given the Hollywood treatment in Contact and Interstellar but Terno says the movie depictions are forbidden by the laws of physics.

He did this specifically for the sci-fi novel Contact, written by his friend Carl Sagan, which was subsequently made into a movie starring Jodie Foster in 1997.

After this, wormhole research boomed. In the last 10 years or so wormholes have been seriously considered as possible alternative explanations for black holes, and are searched for as potentially real astrophysical objects.

How to design a wormhole

- Design the geometry of spacetime you need, along with additional requirements such as your optimal travel time and the need to survive the journey.

- Take Einstein’s equations of general relativity and figure out the materials needed to make your wormhole.

The 2014 movie Interstellar provides an outstanding illustration of the relevant physics. And, just like a mouth and throat, you would get in and out through the 'mouth', an orifice that is connected by a throat.

While the outcomes of this design may violate our beliefs about what’s normal, it does not strictly violate any of the established laws of physics. To get a traversable wormhole you must have negative energy in some region around it. Normal matter is not like that, but quantum mechanics allows negative energy, and its effects have been observed in experiments.

Wormholes are weird

A lot of current research into wormholes is about their design, the types of matter that goes into them and how to make the whole enterprise less weird.

The sci-fi wormholes cannot be reached, but those that can be built will burn you up and/or tear you to pieces.

English theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking also made the point that if you have two wormholes, you can have a time machine. Again, quantum gravity may allow for this type of weird stuff.

Wormholes (or the maths, at least) are related to black holes

Mathematically, the conditions required for spacetime to contain a wormhole are similar to the conditions required to have a black-hole horizon (technical term: apparent horizon), plus a bit more.

Our recent research works out the consequences of what it means to have a black hole at this moment of time. We also require that it forms in finite time and that going through its surface does not tear you apart.

When this is done in spherical symmetry (many models of black holes – and all detailed models of wormholes – are done only in spherical symmetry), it is possible to describe what can go on around a black-hole horizon, and therefore a wormhole.

What I’ve done to wormholes

I analysed the popular models that describe wormholes – of the type that are popular in both sci-fi and as physical models – and looked at how they could develop in allowed physical processes.

Without violating the known laws of physics, it turns out that none of the allowed black-hole solutions, even ‘bad’ ones, (remember, from the maths perspective, you look for a wormhole by first asking, “Can it be a black hole-like thing?”) can be extended to get us a good wormhole.

The sci-fi wormholes cannot be reached, but those that can be built will burn you up and/or tear you to pieces.

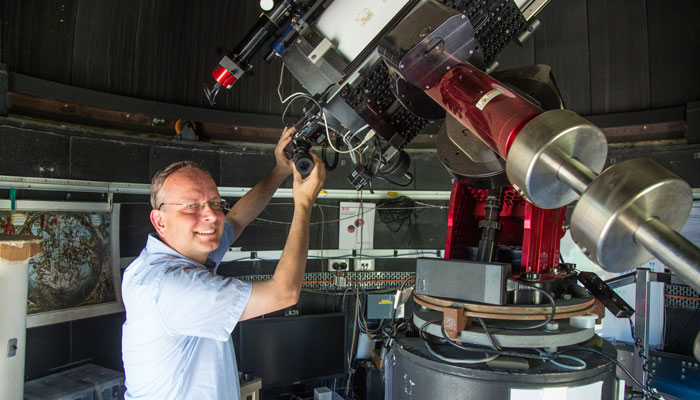

Hollywood licence: Associate Professor in the School of Mathematical an Physical Sciences Daneil Terno (pictured) says the wormholes of science fiction movies are not scientifically sound.

The most popular wormholes from sci-fi are forbidden by the laws of physics. And those that will kill you if you try to travel through them. In spherical symmetry, sci-fi wormholes cannot form. And the ones that can form are no good for sci-fi unless we allow quantum gravity, for example, to operate on a much larger scale than we presently think is possible.

Sorry, everyone.

Daniel Terno is an Associate Professor at the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences and Deputy Director, Centre for Quantum Engineering. He is also affiliated with the Centre for Astronomy Astrophysics and Astrophotonics.