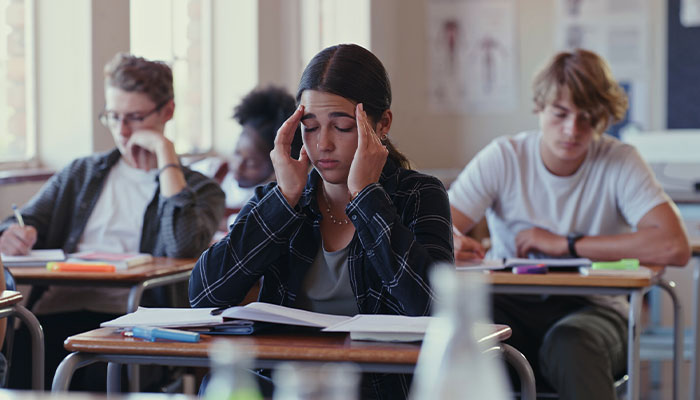

Year 12 is a stressful time for every teenager, but teachers who think they are acting in their students’ best interests may only be increasing anxiety for the students and themselves in the process.

Anxious beginnings: About 19 per cent of Year 12 students could be classified as clinically stressed going into the Year 12 period, the study found.

Professor Viviana Wuthrich and Dr Jessica Belcher from the School of Psychological Sciences carried out a study of 367 Year 12 students and 96 teachers from seven public and private schools across the Greater Sydney area to assess the effect of using fear appeals on stress levels in students and teachers.

Anyone who has seen COVID-19 messaging or the warnings on cigarette packets is familiar with the use of fear appeals.

They are designed to create anxiety, and they can be effective when there is a real risk to people’s health and urgent behaviour change is needed.

High levels of stress aren’t related to how bright they are, or which schools they go to, but girls do tend to be affected more than boys.

Wuthrich says fear appeals at school often begin with “the talk” given at the start of Year 12.

“The principal emphasises how important the year is, that it’s the summation of their education and critical for their future career, so they need to make the most of it,” she says. “It’s the key to their success in life, and there will be negative consequences if they don’t knuckle down and work hard.

“It might be done with the best intentions, and for some students it can be effective in motivating them, but for others it has the opposite effect.

“It’s not just that one talk either – students reported regular reminders from their teachers throughout the year.”

Which students are most affected?

Wuthrich, who has done a number of studies on the effects of Year 12 on students’ mental health, says it’s no surprise to anyone that the final year of high school is a particularly stressful time.

“About 19 per cent of Year 12 students could be classified as clinically stressed going into the Year 12 period,” she says.

“High levels of stress impair their ability to concentrate and study, affect sleep, and can ultimately reduce their performance at exam time.

“Stress fluctuates throughout the year, and high levels aren’t related to how bright they are, or which schools they go to, but girls do tend to be affected more than boys.

- How to put your phone down: Tips from a psychologist

- High noon on high petrol prices as excise relief ends

“The main factors are a predisposition to anxiety, and lower academic self-efficacy, which is their belief in their own ability to complete the course work.

“So, fear appeals aren’t the only thing driving Year 12 stress, and they’re not even the main player, but they do heighten it significantly for students who are already vulnerable.”

Fear appeals also hurt teachers

Belcher says the study found teachers who used fear appeals with their students were more likely to report higher levels of anxiety and lower levels of confidence in their teaching ability.

Setting the scene: Professor Wuthrich says 'fear appeals' at school often begin with 'the talk' given at the start of Year 12.

And the use of fear was more common in newer, less experienced teachers, especially those who had underlying anxiety, both of which affect their confidence.

“If teachers are already prone to being anxious, the students failing seems more of a threat, and we think that’s why they give these talks,” she says.

“No university is telling their teachers in training that this is a good practice, but this behaviour fits in with what we already know about behaviour responses in people who experience anxiety.

“We know anxious people are prone to catastrophising, or expecting the very worst to happen, and this leads them to encourage risk avoidance in others.”

Teacher stress and burnout are both being reported to be at unsustainable levels post-pandemic, but this study was done in 2018, showing the problems are not only COVID-related.

Belcher says if they were doing the study now, it would be hard to tease apart what was due to pre‑existing stress and what was related to newer pressures.

“We know some of that stress is due to factors like increased expectations to have their students perform well and school rankings, and teachers also report a lot of top-down pressure from principals and parents,” she says.

“Teachers with the least experience are the most vulnerable to stress and to leaving teaching, but they are also the ones who are using these fear appeals that undermine their own performance and that of their students.

“It’s just a bad mix for everyone concerned.”

What can we do about it?

Wuthrich says a two-pronged approach is required, focusing on increasing students’ self-efficacy and supporting teachers.

“Instead of trying to instil that fear of failure, teachers should be giving motivating talks that emphasise how far they’ve come and that they have all the resources at hand to really nail it,” she says.

“They have the skills they need and they’re ready for this.

“If we build that underlying resilience and the belief that they are ready for this challenge, it will not only reduce student stress and improve exam performance, it will help create a healthier environment for our teachers.”

Viviana Wuthrich (pictured) is a Professor of Psychology in Macquarie University’s School of Psychological Sciences, Director of the Centre for Ageing and Wellbeing and a member of the Centre for Emotional Health.

Dr Jessica Belcher is a Post-Doctoral Fellow and Clinical Psychology Registrar at Macquarie University.