The wattles are flowering and the days getting longer and slightly warmer – but we’re a few weeks off the start of a new season, according to astronomers, who calculate that spring in the Southern Hemisphere will begin this year on September 23, at 11:03 am, AEST.

However in Australia, it is meteorologists rather than astronomers who dictate the official change of seasons, and they’ve determined that September 1 is the national start of spring.

“I was shocked, when I moved to Australia 16 years ago, to see that everyone used the beginning of December, March, June and September as the change of season,” says Macquarie University astrophysicist Dr Ángel López-Sánchez.

Astronomers define the change in seasons by a solstice (when the sun appears at its furthest distance north or south of the celestial equator) or equinox (the moment when the sun crosses the celestial equator).

López-Sánchez says that Australia and New Zealand differ from most European and American countries which use this astronomical definition for seasons.

How the tilt of the earth affects the seasons

“Seasons are defined by astronomy in a very accurate and precise way, down to the minute,” López-Sánchez says.

Seasons occur because the sun heats its orbiting planets unevenly – an effect increased by the Earth’s 23.3 degree tilt.

The tilt doesn’t change, but the relative orientation of particular regions of the planet will shift during Earth’s orbit around the sun, López-Sánchez says.

Seasons are defined by astronomy in a very accurate and precise way, down to the minute.

“When the Southern Hemisphere tilts towards the sun, Australia spends more time facing the sun so our days are longer, and the sun’s rays strike Earth at a steeper angle so the days are hotter,” he says.

At the same time, similar latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere tilt away from the sun, where the reverse will happen – “therefore it is Winter in the north, and summer in the Southern Hemisphere,” he says.

It's Relative: Seasons occur because the sun heats its orbiting planets unevenly – an effect increased by the Earth’s 23.3 degree tilt - with the relative orientation of particular regions of the planet shifting during Earth’s orbit around the sun.

Between summer and winter, the tilt is less apparent, delivering similar, balmy temperatures in a Southern-Hemisphere spring and Northern-Hemisphere autumn, for example.

The tilt effect is less noticeable in locations close to the Equator, which can experience very little temperature change between seasons, and more pronounced at places closer to the poles, where seasonal temperature differences are extreme.

Two, four or more seasons

Many residents in equatorial countries, where temperatures are often consistent year-round, define just two seasons: wet and dry.

However other communities with far more nuanced seasonal definitions include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language groups with highly localised annual seasons based on complex interactions of plants, animals, water, weather, fire and astronomy.

The Gulumoerrgin people in the Northern Territory define seven main seasons, while the Ngan'gi people of northern WA and Northern Territory recognise 13 different seasons.

“These seasons are used by different groups as a calendar guide to the best time to harvest certain foods or to hunt,” says López-Sánchez, adding that many Aboriginal and non-Western cultures also used astronomy to develop these calendars.

Temperature change

There’s usually a lag between seasonal change and temperature change, particularly in temperate climates like Sydney’s.

“This is because of a phenomenon known as ‘thermal inertia,’ which means that it takes some time for the atmosphere to heat up and cool down,” says López-Sánchez.

In spring, as the hours of sunlight increase, it can take weeks before the atmosphere heats up – and the reverse occurs as we move from summer to autumn.

- Why Australia needs a Media Freedom Act

- VIDEO Caregiver and changemaker: Lucy Brogden's high impact at the National Mental Health Commission

“The relative position of the sun in mid-February and late October is similar, but it is much warmer in mid-February than in late October, because of this lag in heating or cooling the atmosphere,” López-Sánchez says.

Temperatures typically shift from around the half-way point between the equinox and the solstice, he says – adding that many ancient cultures planned festivals such as Halloween and May Day at these mid-season half-way points.

Inter-planetary seasons

López-Sánchez says that astronomical conventions of solstices and equinox don’t just apply to the Earth – they determine the change of seasons on all planets.

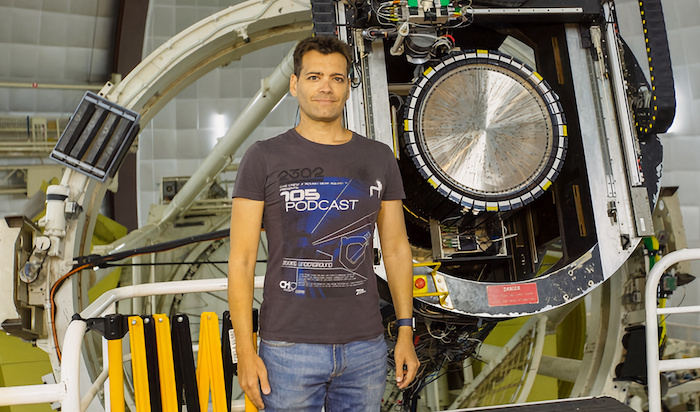

Not so fast: Dr Angel R. Lopez-Sanchez (pictured) says although meteorologists set the official start of Spring in Australia as September 1, astronomers beg to differ, saying according to planetary physics, it does not start until September 23.

The surface of any planet orbiting a star is heated unevenly, because planets are ellipsoid (round-shaped) objects with widely varying axis tilts and elliptical orbits – but on every planet, astronomers can define four seasons, he says.

Earth’s tilt at 23.3 degrees is slightly less than Mars, which tilts at 25.2 degrees.

Despite the thin atmosphere on Mars, in Winter the white caps of ‘ice’ (mostly frozen carbon dioxide) can be seen to grow at the poles, and shrink in the Martian Summer.

Uranus has the most bizarre seasons in our Solar System, due to its extreme, almost-sideways tilt (98 degrees).

Summer sees the Northern Hemisphere of Uranus constantly facing the Sun, with no night for 21 years, while the planet’s Southern Hemisphere, in winter, faces continual darkness.

“That’s a very long midnight sun, or a very long polar night!” López-Sánchez says.

Dr. Ángel R. López-Sánchez is an Astrophysicist and Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Science and Engineering.