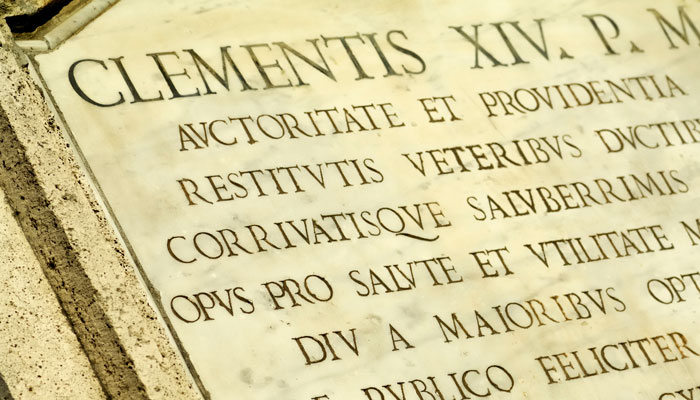

Yes, every picture tells a story, but so does every sherd of pottery. Pottery dates us, it anchors us in a time and place and is the key to understanding why people lived where they did and how they did.

Ancient stories within: Archaeologist Dr Susan Lupack, pictured above, with pottery from the latest exhibition at the Macquarie University History Museum.

“Ceramics unite humankind,” says Dr Susan Lupack, a senior lecturer in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University. “We can see ourselves in ceramics. We understand pottery and relate to it because we all use it and have done so for our entire human history. Ceramics provide the keys to dating the civilisations we dig up.”

Terracotta, or baked clay, has been a close companion of humankind for around 30,000 years and was first used to fashion figurines of both animals and human beings. Some of the earliest pottery vessels, found at Xianrendong Cave in the Jiangxi province of China, go back nearly 20,000 years. Pottery is to antiquity, you could say, what plastic is to the 20th and 21st centuries.

A new exhibition at Macquarie University, Dust of the Earth: History from a Pottery Perspective (on until April next year), puts pottery in the spotlight, analysing its shapes, decoration, glazes and markings. In tandem are illustrations, texts and photos.

Pottery represents culture. To have something that is useful and beautiful at the same time, that you can hold in your hands – that’s what I love about it.

One of the exhibition’s strengths, says Dr Lupack, is its broad range of dates and geography. There are specimens relating to the Mediterranean regions (Turkey, Greece, Rome), Egypt, China, Islamic nations such as Iran, and Australia.

Sherds – and a whole bowl from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) are amongst the oldest in Dust of the Earth – dating to 7000 years ago. A little larger than a cereal bowl but smaller than a salad bowl, it features bright red decoration on a cream background, typical of what is sometimes called 'flameware'.

Crude beer jars and bread moulds from burial sites in Ancient Egypt around the 6th Dynasty paint a picture of relatives bringing food and drink in easily transportable vessels to visit their dead ancestors.

LEFT image: Figural pot, ceramic, Chimú culture, modern Peru, c. 1000 – 1500 CE. RIGHT image: Demijohn, ceramic and metal, manufactured by Fowler, Sydney for Sharpe Bros., Sydney, c. 1900 CE.

Among displayed pottery from Ancient Greece are ceramic fragments with black-figure decoration (ca. 650-500 BCE) and a red-figure drinking cup (reflecting the warm red colour of local clay) depicting the Theban mythical hero Actaeon who, according to mythology, was torn apart by the man-eating hounds he had raised.

But sometimes, says Dr Lupack, their images simply showcase everyday life – women working at a loom or a group of workers whacking olives out of a tree.

Ancient Rome’s love affair with everyday pottery is seen in plates, bowls, mould-made oil lamps and decorative figurines unearthed through the ages. Not to mention bricks, tiles, pavements and water pipes. Popular was red-gloss ware, or terra sigillata, often adorned with relief decoration – also mould-made. Discoveries of red-gloss ware made as far afield as Sudan, India and Scotland were evidence of a thriving ceramics trade.

Chinese ceramics are among the most significant and sophisticated of ceramics. As early as the 3rd century BCE, technology and firing techniques were advanced to levels otherwise unheard of, the Terracotta Army being the most famous example. The Chinese were also famous for the porcelain jars that transported salt, spices and ginger, most depicting landscapes, floral and vegetal motifs, and animals.

On display in the exhibition is a large 19th century Chinese porcelain jar on a wooden stand with a domed lid set with a foo-dog finial, depicting cabbage leaves and insects.

Form and function

Social messages are at the heart of Islamic pottery, and some of the items in Dust of the Earth are “incantations” that hark back to Eastern Iran in the 10th century.

There’s a focus, too, on Australian pottery, including pottery from convict artist Jonathan Leak, dating from 1821 to 1838, and pottery from Bendigo which became a major production centre from the 1860s to the 1920s (24 vessels found on a Victorian sheep farm are in the exhibition).

Dust of the Earth is not all ancient history. Ceramics are movers and shakers in the 21st century, too. With contributions from oxides, nitrides, carbides and borides, 'invisible ceramics' turn up in catalytic converters, car brake pads, dental crowns, and toilets. Ceramic material helps draw heat out of mobile phones and has aerospace applications. In steelmaking, refractory ceramics line furnaces and in many cities around the world ceramic drains still transport water.

Luxury watchmakers have made much of their scratch-resistant ceramic bezels.

Dr Lupack confesses to being a passionate collector of pottery herself, mostly bowls from places she has lived, worked in and visited, including Singapore, Tokyo, Thailand, Turkey, and of course Greece, whose ancient culture is the focus of her archaeological research.

Daily life revealed: Archaeologist Dr Susan Lupack, pictured above, says pottery unites humankind.

“The aesthetics of pottery is just so beautiful,” she says. “From the celadon [green] glaze so representative of Thailand, to the blue and white that says Japan, to the colourful glazes of the Mediterranean and Near Eastern regions – pottery represents culture. To have something that is useful and beautiful at the same time, that you can hold in your hands – that’s what I love about it.”

The Macquarie University History Museum, at 25C Wally’s Walk, is open weekdays 10am-5pm.The museum’s 18,000 objects trace the journey of humankind over five continents and more than 5000 years.

Dr Susan Lupack is recently returned from conducting fieldwork in Greece, where she provides Macquarie University students with archaeological experience as part of the Perachora Peninsula Archaeological Project, which she co-directs with Panagiota Kasimi, Director of Antiquities of the Corinthia. Dr Lupack gratefully acknowledges the Gale Fund, which makes the project’s research and student experiences possible.