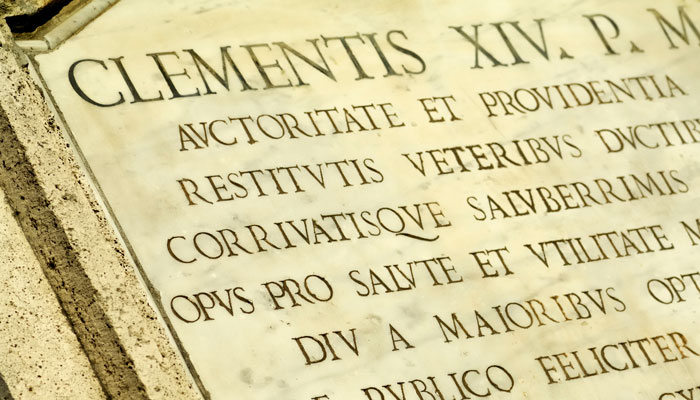

More than 200 objects have travelled from the British Museum in London to Canberra for the new exhibition, each one with a separate story explaining both its use in ancient Rome and its journey to the London Museum.

My colleague at Macquarie’s Department of Ancient History, Professor Bronwen Neil and I attended the opening and together we set about the difficult task of selecting five objects that represent why this exhibition is a must-see.

A trio of treasures: The marble heads of Augustus and Titus, along with a brass oil lamp. Image: © Trustees of the British Museum, 2018. All rights reserved.

Marble head of Augustus

The Emperor Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) makes an appearance - appropriately in Italian marble. He boasted that he found Rome a city of brick and turned it into a city of marble.

Yet, all is not quite as it seems – this bust after its discovery has had some work carried out on it. The nose has been carefully replaced and the curators at the British Museum consider the chin and lips to have been re-worked, so that the item had a greater sale value on the antiquities market prior to its acquisition by the British Museum in 1888.

See if you can spot the carefully disguised glued on replacement nose. However, this restoration chimes well with the other known busts of Augustus with his hair carefully coiffured in the style of a monarch such as Alexander the Great.

Marble head of Titus

There are other emperors to be seen - my personal favourite is the bust of Titus, whose place in history is not so much for his short reign, during which mount Vesuvius erupted to destroy the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and Rome was savaged by fire, but for his capture of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple of the Jewish religion.

Some of the booty from this event is represented on the Arch of Titus in Rome and the money paid for the Colosseum, perhaps Rome’s most iconic monument.

Titus’ bust is unlike that of Augustus – it is less idealised, his face is plumper and, as you gaze at his face, you notice the eyes are narrowed with a sense that you are staring down a powerful commander and ruler of Rome. Try to imagine this sculpture as painted to give yourself the full view of looking into the face of a Roman emperor.

Glass cinerary urn

Within the exhibition, there are a whole range of vessels for containing the remains of the dead, from a ceramic vessel in the shape of a hut – similar to those of the mythical time of Romulus – through to a remarkable glass jar that held cremated remains from the county of Kent in the UK.

This square glass bottle was reused as cinerary urn. Image: © Trustees of the British Museum, 2018. All rights reserved.

This massive glass vessel, almost 40cm (15.7 in) in height in thick green glass, is another highlight from the exhibition. Glass was one of the products shipped in bulk from the eastern Mediterranean into western Europe in the Roman period and subsequently recycled and remade. The survival of glass is one of the features of many Roman cemeteries, either as containers or as vessels to accompany the dead.

Brass oil lamp

There are plenty of the Roman gods on show at this exhibition, often making their appearance in a quite humble or utilitarian format.

Jupiter appears on an oil lamp that would have been hung from a hook. He stands framed by two pillars and an arch and we need to imagine how he would have appeared in the light of the two flames at the front of the oil lamp.

This object was found in Diocletian’s Baths in Rome in the 17th Century or perhaps even earlier. It made its way to the British Museum almost a century later, where it was purchased for a little over £1 ($1.8). Jupiter is shown holding a thunderbolt and sceptre but if you look closely you will notice that there is a dog at his feet. We tend to find Jupiter with an eagle rather than a dog.

Silver horse trapping

One of the highlights from the later Roman period is the silver horse-trapping from the Esquiline Treasure, discovered in 1793, which displays some of the best 4th Century CE silver work. This item was found alongside 57 other objects that were traded first to Paris and then purchased by the British Museum in 1866.

The cast silver items were gilded and engraved. These also feature an eagle and heads of lions, with a crescent moon hanging below the eagle – a symbol of the goddess Luna. We find the moon pulled by a chariot in a number of representations of the goddess.

It is fascinating to speculate what the image of the moon on this horse harness actually meant to those who rode the horses or rode in a vehicle drawn by four horses with these trappings.

The silver horse trapping is engraved with three lion heads and a striding eagle in relief. Image: © Trustees of the British Museum, 2018. All rights reserved.

One of the great things about the exhibition is that visitors can use the British Museum’s online catalogue to find out a bit more about each object, because each label includes the catalogue number that also reveals the date of acquisition in the first four digits. For example, 1866.1229.26 refers to the acquisition of the silver horse-trapping in 1866.

Each of these objects has a really rich history, not just of what it was or meant in antiquity, but also the story of how it made its way to the British Museum.

Seeing the exhibition reminded me that I visited the British Museum for the first time when I was around four years-old and that I visited it frequently from then on because my mother worked across the road in the Bloomsbury area of London. From the age of seven, I explored the galleries and was fascinated mainly at that time by the Sutton Hoo burial and the Vikings.

At some stage, Rome came into play and I have to thank the British Museum for inspiring my interest in the past that has become my profession and has led me to Macquarie University. It is only appropriate to find such a rich collection of objects from the British Museum, on display at the National Museum of Australia.

- Prof Laurence's book Rome, Ostia, Pompeii: Movement and Space is now available in paperback.