Researchers in Macquarie University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy are currently gathering data that could see Palm Beach, at the tip of Sydney's Northern Beaches, establish itself as an official sanctuary against the growing global problem of light pollution.

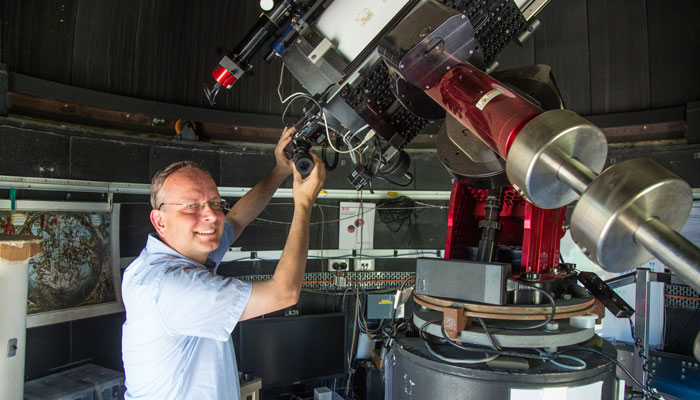

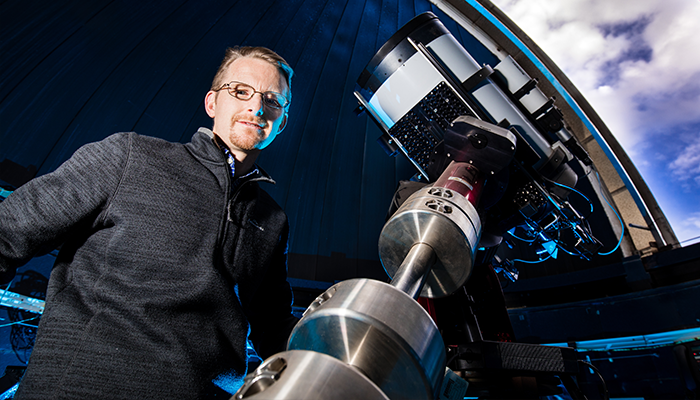

Starry, starry night: Led by Macquarie University astronomer Dr Richard McDermid, scientists are making a case to the Northern Beaches Council to establish a light pollution-free sanctuary over Palm Beach.

“Very few people would consider light as a dangerous thing, but it’s actually one of the fastest growing pollutants in the world, with light pollution growing at average yearly rate of two per cent,” explains Macquarie University astronomer Dr Richard McDermid.

“Aside from the obvious impacts on our astronomical research, light pollution also has some really concerning impacts on human health and our environment. Research has shown that it is interrupting animal breeding cycles, especially in nocturnal species, and we’re only just starting to understand the impacts of artificial light on the human brain.”

“Even something as seemingly innocent as the uplights that illuminate gardens at night – it’s all cumulatively contributing to increased amounts of artificial light in our night sky.

Dark sky reserves – also sometimes called dark sky parks or dark sky sanctuaries – are designated areas where optimal levels of darkness can be preserved and protected against artificial light pollution.

“The first International Dark Sky Park in the southern hemisphere was created here in Australia 3 years ago, in the Warrumbungle National Park in New South Wales,” explains McDermid . “As an accredited reserve, it is protected by planning guidelines which restrict artificial light within 200 kilometres of the site, which includes the Siding Spring Observatory – home to Australia’s largest optical telescopes.”

Under Dr McDermid’s supervision, Macquarie University’s team is gathering the necessary data for the Northern Beaches Council to make a case for the establishment of a reserve in Palm Beach. The area is home to a colony of micro bats which are particularly vulnerable to the effects of light pollution .

“The tip of Palm Beach, up to the Barrenjoey Lighthouse, is quite dark,” McDermid says. “What we’re doing is are measuring the exact levels against what is considered a baseline optimal level of darkness, once natural light sources are factored in.”

Stars aligning: the Sydney suburb is a favourite escape for well-heeled holidaymakers and now Macquarie University scientists want the skies above it to become the city's first urban dark sky reserve. Pic credit: Visit Sydney.

Seeing the light on light pollution

In a city where developers are increasingly clambering for new land, McDermid says that establishing designated pockets of darkness in Sydney is important – not only to protect residents and local ecology, but to help educate people about the effects of light pollution.

“Even something as seemingly innocent as the uplights that illuminate people’s gardens at night – it’s all cumulatively contributing to increased amounts of artificial light in our night sky”, he says. “People just aren’t aware of the impact.”

Another problem is the growing use of LED lighting – an environmental ‘good guy’ with an unfortunate downside.

Dark sky crusaders: as part of their anti-light pollution project, the Macquarie team measures night-time darkness levels at Sydney’s Palm Beach.

“While LED lights are great in terms of energy saving, they can contain a lot more blue light, which scatters much more than warm light and contributes more to light pollution,” says McDermid.

As a Board Director of the Australasian Dark Sky Alliance – a rather Star-Wars-y sounding organisation dedicated to reducing light pollution – McDermid is part of an interdisciplinary movement that is bringing together everyone with a stake in the preservation of the night time sky, to draw attention to these mostly unknown effects of artificial light.

- First accurate 3D map of the Milky Way reveals a warped galaxy

- New scam-busting toolkit could save your number from being hijacked

“We’re looking at things like developing a ‘seal of approval’ for lighting fixtures that emit low levels of light pollution,” he says. “But our first step is awareness.”

“The good news is, fixing light pollution is amazingly simple – you just turn off the light, and it’s gone,” says McDermid. “But people have to flick that switch.”