Conservationists worldwide were left reeling following the death of Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhinoceros on earth, on 19 March 2018. In the years preceding his passing, Sudan became an icon symbolising the impact of human-caused extinction, in particular, at the hands of poachers and trans-national criminal syndicates.

Despite some 10 000 km separating the African and Australian continents, news outlets and social media joined the global outpouring of grief, with #rememberingsudan trending. However, local audiences were left with one resounding question: what can be done in Australia?

INVESTING IN EXTINCTION: Zara Bending from the Macquarie Law School hopes a Senate Inquiry will bring an end to the ivory trade in Australia.

Earlier that month, hundreds converged on Melbourne's Bourke Street Mall, for the Australian Elephant Ivory and Rhino Horn Crush, in celebration of World Wildlife Day. The event, the first of its kind in Australia, called on the Federal Government to join the United Kingdom, the European Union, Hong Kong, the United States and China in imposing stricter regulation on the domestic trade in wildlife products.

A response could well be on the horizon.

Investigating the link between poachers and auctions

The Senate’s Parliamentary Joint Committee on Law Enforcement launched its inquiry into Australia’s domestic trade in ivory and rhinoceros horn on 28 March 2018. Among the terms of reference, the inquiry seeks to examine whether the legal domestic market is contributing to poaching or illegal trade; to investigate whether the legal domestic markets should be reformed or closed; and consider whether law enforcement agencies have relevant training to assess age and provenance documentation of items imported into Australia.

While rhinoceros poaching effectively stopped in the 1990s (with limited incidents occurring in the early 00s) it was the resurgence of Vietnam as a major destination of import in 2008 that heralded the start of the current poaching crisis despite the imposition of CITES provisions. For example, it is illegal to import or export rhino horns without a certificate issued by government officials in Australia or overseas stating that the item was acquired prior to 1975.

Now, approximately three rhinos are killed each day in South Africa alone.

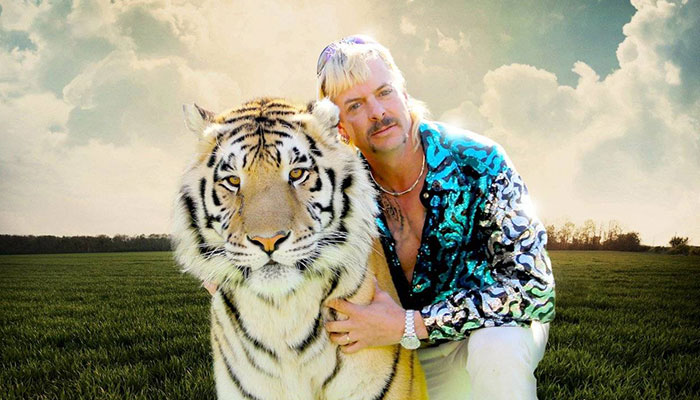

SCARCITY DRIVES PROFIT: For each horn seized, many more penetrate borders to be put on sale in Australia, says Bending.

Research conducted by the UNODC, INTERPOL, TRAFFIC and IFAW underscores the importance of domestic regulation in minimising the risk of legal markets acting as conduits for illegal trade. What’s more, it appears that a growing segment of consumers are effectively ‘investing in extinction’ by purchasing ivory and rhino horn products and banking on the increasing rarity of species driving profit margins.

In the past decade, 322 imported ivory items were seized by Australian Customs in addition to 24 rhino horn products. However, for each piece confiscated it is likely that hundreds penetrate the border and enter the legal market which does not require evidence of legal import, provenance or age at point-of-sale.

Horns for sale online

A quick search of auction houses, including online platforms like Invaluable.com, easily generates visible Australian listings. As for known value within Australia, IFAW identified a carved horn libation cup which had sold for AUD$67,100 through Bonhams (Sydney) in 2014 despite public outrage not dissimilar to that which caused Lawsons (Sydney) to withdraw a pair of black rhino horns valued of $AUD50,000 - $70,000).

Western Australia based auction house McKenzies recently listed a pair of black rhinoceros horns, a rhino horn foot, and a ‘large elephant ivory tusk’ for an auction that was due to run today.

While it appears that these three lots have been removed following public outcry, the auction still has other carved ivory items listed for sale.

Compounding the problem further, online traders sell all manner of illicit wildlife products through social media platforms, some more conspicuously than others.

Reflecting the severity of the problem, in March WWF, TRAFFIC and IFAW launched the Global Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online partnering with up 21 tech companies including the likes of Google, eBay, Facebook, and Instagram. The aim is to reduce illegal online trade in wildlife products by 80 per cent by 2020. Still, such efforts have been labeled as nothing more than a ‘paper tiger’ due to alleged inaction. In the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook was accused of running ads on webpages run by ‘overseas wildlife traffickers illegally selling the body parts of threatened animals’.

Now confronted with the extinction of two of the planet’s most iconic mammals, Australia has the opportunity to design and implement effective regulatory reform to do its bit to secure a future for our charismatic megafauna and challenge the paradigm of ‘high profits, low-risks’ that make the illicit wildlife trade so attractive to syndicates and investors alike.

Listen to Zara Bending on the 2SER Breakfast show on July 4 talking about her appearance before the Parliamentary Committee enqury into the Illicit trade of rhino horns.

Zara Bending is a doctoral researcher and academic at the Macquarie Law School, Associate of the Centre for Environmental Law, and Board Director of the Jane Goodall Institute Australia. She is author of the recent lead article in the May issue of Environment and History:

Zara J Bending, 'Improving Conservation Outcomes: Understanding Scientific, Historical and Cultural Dimensions of the Illicit Trade in Rhinoceros Horn' (2018) 24(2) Environment and History 149-186. (link:http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/whp/eh/2018/00000024/00000002;jsessionid=2uu6cu8n809ga.x-ic-live-02).