In early April, news broke that Nadia, a Malayan tiger at the Bronx Zoo in New York, had tested positive for the novel coronavirus. One of seven big cats showing symptoms, hers was the first case of a non-domesticated animal testing positive. Nadia likely contracted the virus from an asymptomatic zoo staffer.

Waiting for evidence: Though a Malaysian tiger at the Bronx Zoo was diagnosed with coronavirus, its still unclear whether or not domestic or zoo animals can transmit the virus to humans.

Pet owners, already on high-alert for COVID-19 updates and highly reliant on their own furry companions to cope with social distancing, again flooded social media with queries about inter-species transmission.

Currently, there is no evidence of domestic or zoo animals transmitting the virus to humans, and reports circulating of infection in domesticated animals are limited (for example, a cat in Belgium, and a couple of dogs and a cat in Hong Kong).

While Nadia’s diagnosis raises concerns regarding how the virus may present in animals, the vigilant response of trained staff demonstrated the level of care afforded in reputable and accredited zoos.

The real story behind Tiger King

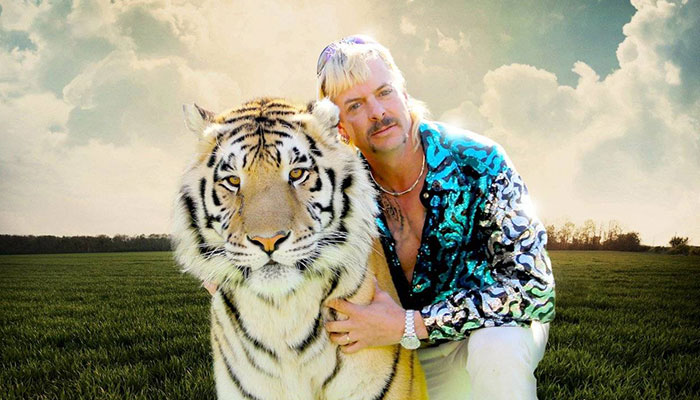

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the big cats whose stories took a back seat to the human circus showcased on Netflix’s Tiger King, a popular isolation binge-watch.

The cult of personality manufactured around featured felon ‘Joe Exotic’ has left conservationists filling in the gaping holes in the series’ treatment (or rather maltreatment) of the supporting cast of animals.

There are fewer than 3900 tigers in the wild, occupying a mere 4 per cent of their historic range. Despite this alarming statistic, there are more tigers in captivity, living out their lives as exotic pets, exploited by disreputable wildlife attractions, or bred for parts in farms around the globe.

Tiger King glossed over animal cruelty and welfare concerns, and side-stepped the risks associated with up-close attractions like ‘cub-cuddling’.

In the United States, there are an estimated 5000 captive tigers (although no one actually knows in the absence of federal or uniform laws). Of those, only about 6 per cent are kept in accredited zoos and facilities.

Binge or cringe-worthy? Netflix's Tiger King series has conservationists in an uproar over maltreatment of animals in private attractions. Image credit: Netflix.

Despite the common claim that animals kept in private collections and roadside attractions will one day contribute to the ongoing health, survival and growth of wild populations, a range of behavioural and genetic factors prevent this.

Indeed, Tiger King failed to make the distinction between accredited and non-accredited zoos and sanctuaries, glossed over animal cruelty and welfare concerns, and side-stepped the risks associated with up-close attractions like ‘cub-cuddling’ (a practice known to fuel the illegal trade in wild animals).

The link between pandemics, illegal wildlife trade and habitat loss

Which brings us back to COVID-19.

Last week, TRAFFIC, a leading NGO specialising in wildlife trade, published its report Wildlife trade, COVID-19 and zoonotic disease risks. The report reiterates that while the precise origins of COVID-19 remain unproven, there are strong indications of early cases in China involving humans who either worked at or visited a market in Wuhan where wild animals were on sale, “and initial research results pointed to a possible transmission pathway from bats via pangolins to people”. Pangolins are the most trafficked mammal in the world.

Zoonotic disease, meaning illness that can be transmitted from animals to humans, is not a new concern. Two-thirds of all infectious diseases presenting in humans originated in animals. These include SARS, MERS, Avian flu, Ebola and H1N1.

What is currently concerning researchers is the escalating risk of transmission as humans come into closer proximity with wildlife through direct exploitation (for example. the hunting and illegal trade in wild animals, their parts, or derivatives) or through changes in movement (that is. humans encroaching into habitat and/or wild animals being pushed into human-occupied areas).

Lessons learned?

Despite experts warning for years of a pandemic, and now projecting forward to the next, world leaders in favour of 'business as usual' have generally been slow to act. As a species, we appear to be slow learners, as reports from the London-based non-profit Environmental Investigation Agency have demonstrated in recent weeks.

Despite well-publicised bans on wildlife consumption in China and Vietnam, some physical markets continue to operate with impunity, with a bulk of traders (like many of us) now moving their businesses online.

Hundreds of organisations are calling for the end of captive ownership, breeding, domestication and use of all wildlife.

Rhino horn has predictably been touted as a COVID-19 cure by traders in China and Laos (without any scientific basis), and a list of COVID-19 treatments published by the Chinese government included a traditional medicine containing bear bile.

What about tigers? No goods news there, as EIA also uncovered a Vietnamese trader using social media to market his tiger bone 'glue' as a health tonic to boost immunity during the pandemic.

Where to from here?

Now that wildlife concerns have truly entered the popular dialogue around public health, there are questions as to how we proceed.

Wildlife trade now on the radar: while the precise origins of the virus remain unproven, there are strong indications of early cases in China involving humans who either worked at or visited a market in Wuhan where wild animals were on sale, according to a TRAFFIC report released last week.

Reports out of Canberra indicate that the Australian government will be lobbying China to enforce its bans on the consumption of wild meat. Hundreds of organisations around the world are more broadly calling for the end of captive ownership, breeding, domestication and use of all wildlife.

- Your at-home crash course in English literature

- How to manage extreme economic events during times of uncertainty

However, experts from Oxford University have cautioned against blanket bans on wildlife trade, instead favouring enhanced regulation embedding public health around zoonotic diseases.

Whatever the solution, it is imperative that it be evidence-based. If there’s anything we’ve learned from this pandemic (as so many have in Hollywood disaster films) it’s that so much can and will go wrong when the expert in the room goes ignored.

Zara Bending is a doctoral researcher and academic at the Macquarie Law School, Associate of the Centre for Environmental Law, and Board Director of the Jane Goodall Institute Australia.