Widespread trade union calls to extend special paid leave to casual employees in the early days of the COVID-19 crisis highlighted existing inequalities in our national employment standards and the immense social risk of labour insecurity.

Doing it tough: two thirds of food services workers in Australia are casuals without paid leave entitlements, and the majority of those are women,

Current circumstances are particularly onerous for casual workers with no paid leave entitlements, who make up around one-quarter of all employees and earn an average $9 less per hour than their permanent co-workers. When this proportion is combined with independent contractors and sole-traders, more than a third of the workforce are without paid leave entitlements.

Hardest hit by the COVID-19 crisis is the accommodation and food services workforce, two-thirds of which is comprised of casuals whose livelihood is being undermined by the closure of restaurants, cafes, pubs and other recreational venues. The impact is also being felt by retail workers, with 38 per cent in casual employment.

For workers who live from paycheck to paycheck, lost hours and extended closures threaten capacity to buy essential household items and pay rent, increasing the risk of eviction.

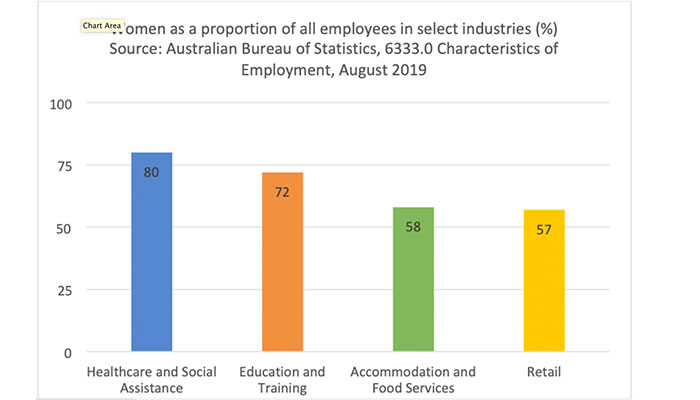

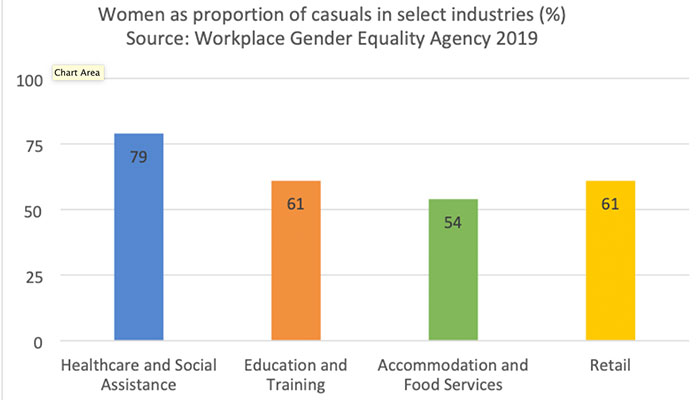

In public-facing industries impacted by COVID-19, women comprise the larger part of the workforce, but the majority of casual employees.

In 2017, policy analysts Elise Gould and Jessica Schieder estimated that seven and a half days of lost income could impact the ability to pay rent for a month. Two and a half days of lost income could cost an entire month’s worth of groceries.

Prevailing gender inequality in the workforce means that employment insecurity disproportionately affects women. While women are 50 per cent of all employees, they are 57 per cent of employees without leave entitlements and 61 per cent of award-reliant employees, earning an average $242.90 per week less than men.

In public-facing industries impacted by COVID-19, women comprise the larger part of the workforce, but the majority of casual employees (see Tables 1 and 2). Critical frontline services in healthcare and social assistance have a workforce that is 80 per cent female, with women accounting for 79 per cent of casuals.

In childcare and schools, services that remain open in most states, women are 86.7 per cent and 72.5 per cent of the workforce respectively.

Graph 1: Women as a proportion of all employees in select industries (%). Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 6333.0 Characteristics of Employment, August 2019

Graph 2: Women as proportion of casuals in select industries (%). Source: Workplace Gender Equality Agency 2019

The current threats to women’s livelihood are compounded by the fact that women perform the greater share of unpaid care work. Globally such work is equivalent to 2 billion people working on a full-time basis and accounts for 41.3 per cent of GDP in Australia.

In households with children where both partners work full-time, women perform nearly two-thirds of housework and care work. In households with children where only the male partner works full-time, more than 70 per cent of housework and care work is undertaken by women.

Rising impact on women's care burden and risk

Excessive amounts of unpaid care work impacts women’s ability to gain formal employment and affects women’s health. It also creates what the International Labour Organisation calls the 'job quality penalty', an increased likelihood that women will be in low-quality work.

Australia’s public expenditure on care policies that would alleviate unpaid caring responsibilities continues to be low by international standards, at around 3 per cent of GDP. The provision of at-home care for family members affected by COVID-19 will increase women’s care burden and could place them at a disproportionate risk of acquiring the infection.

Employment insecurity is an important social determinant of health. Perceived job insecurity, even without actual job loss, has an adverse effect on health outcomes. In a 2018 study, workers in precarious employment were five times more likely to report poor or fair general health, and three times more likely to report poor or fair mental health.

Temporary workers are more likely to present ill at work due to financial pressures. Universal access to paid sick days would ensure that workers are not financially disadvantaged and reduce workplace transmission.

Single-female and single-parent households are particularly vulnerable to financial distress.

In an economic environment where women are over-represented in insecure, low-quality, and low-paid work without protections, single-female and single-parent households are particularly vulnerable to financial distress, which can be seriously exacerbated by lost income due to serious illness or injury.

The government’s second coronavirus stimulus package provides income relief for casual and contract workers facing increased vulnerability to income insecurity, and offers protection to workers facing immediate threats of job loss during the COVID-19 crisis.

The more recent JobKeeper scheme, implemented after wide-spread calls for a UK-style wage subsidy, provides a partial buffer against unemployment by supporting employees and sole traders who have been stood down or are at risk of losing their jobs.

This is dependent on their employers signing up for the scheme, and there is a one-month lag before payments commence. Troublingly, while the scheme includes casuals, those with irregular employment arrangements or breaks in service are unlikely to qualify. This could mean the exclusion of a large number of sessional academics in higher education.

A six-month moratorium on evictions is a welcome announcement, however, the scheme relies heavily on informal negotiations between tenants and landlords. Many of the specific details of how the scheme will work are yet to be determined.

Policies to halt rent and utility payments, as well as mortgage repayments should also be implemented in conjunction with the moratorium, as these would allay the devastating impact of lost income for casual and contract employees.

Stimulus packages don't fix underlying problems

Provisions for special access of up to $10,000 in superannuation for casuals and contractors may also offer immediate income relief, but this will come with a long-term cost that reinforces future insecurity, particularly for women who have up to two-fifths less super than men. This is exacerbated by the prevalence of casual work and the gender pay gap.

While these measures will help to mitigate against a surge in unemployment and labour insecurity in the short-term, they do not address the systemic inequalities in our employment standards that the global health crisis around COVID-19 have made starkly evident.

The exposure of a considerable proportion of the workforce to labour insecurity makes women unduly vulnerable to financial distress, due to their over-representation in precarious work, particularly within industries with higher proportions of casual employees.

Only policies that address labour insecurity and extend access to employment protections, combined with improved funding for childcare and elder care services, will alleviate women’s disproportionate vulnerability to future crises.

Dr Nour Dados is a member of the Centre for Workforce Futures at Macquarie University.

Professor Lucy Taksa is a Director of the Centre for Workforce Futures at Macquarie University