With house-bound time on our hands during the coronavirus crisis, the time may never be better to lose ourselves in some of English literature’s finest, most enjoyable books.

To give your reading shape and meaning, Macquarie University English Professor Louise D’Arcens selects 10 of her favourite texts that take us through the history of English literature, telling great stories of their time that still help us make sense of our world today.

The selected books show how the English language has made itself available to tell stories of different cultures and places far beyond the land of its origin. They bring us characters with timeless humanity, and themes with a relevance that endures right now in 2020.

Let the reading begin:

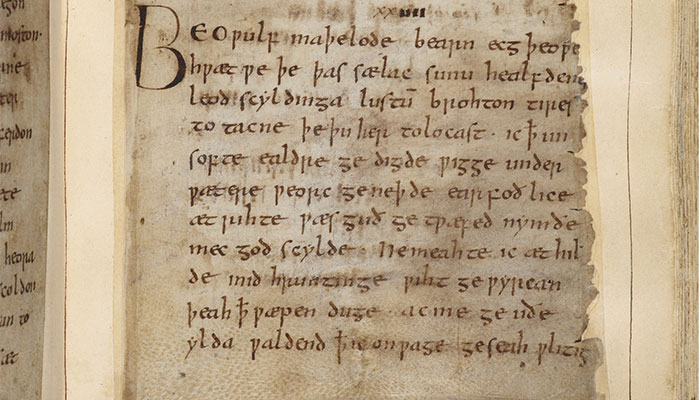

1000AD:Beowulf

By Anonymous

This is the earliest narrative epic in the English language, written in Old English towards the end of the first millennium AD by an anonymous poet.

Beowulf is a heroic tale of the warrior Beowulf and his battles with the otherworldly creatures Grendel and Grendel’s vengeful mother, and then later on in his life, when he’s king, his battle with the dragon guarding a hoard of treasure. Beowulf has been incredibly influential on all sorts of later writing, and particularly on authors such as J.R. R. Tolkien and fantasy fiction in general.

Trailblazer: The original manuscript of Beowulf, kept in the British Library. Photo: British Library

I would recommend people to read the brilliant translation by the late Nobel Prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney, who brings his sense of Irish idiom to the way he translates Old English.

Watch: There are a few adaptations, but the one I would recommend is Robert Zemekis’s 2007 movie version. It was controversial among people who know the text, for a few reasons – one being the casting of Angelina Jolie as Grendel’s mother, who in the poem is like a hideous swamp hag.

If you like Beowulf, also try: The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien

1300s: Sir Gawain and The Green Knight

By Anonymous

This 14th-century narrative poem is a delightful example of medieval romance, connected to the beloved Arthurian stories from the time. It is focused on Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur’s Round Table who has left the exulted court and finds himself in a situation very much out of his comfort zone, where his sexual purity and courage are tested.

It’s a very humane story about understanding your own weaknesses, and how people reckon with their own imperfections and failures, and also how communities deal with their humanity and the way they uphold heroes.

There is something about Gawain’s vulnerability as a hero – his intense humanity – that makes his appeal enduring.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight continues to be quite frequently reworked for children; there is something about Gawain’s vulnerability as a hero – his intense humanity – that makes his appeal enduring. The story is always relevant. I taught it to first year university students recently, and they loved it. Like Beowulf, it is important in the heroic tradition.

It was written in Middle English in a Midlands dialect from the later 14th century, which is not an easy read for a modern reader, so I recommend the very admired translation by the UK’s Poet Laureate, Simon Armitage.

Watch: A film version written and directed by David Lowery (Pete’s Dragon, The Old Man and the Gun) is scheduled for release in May. Called The Green Knight, it stars Dev Patel as Gawain – it will be interesting to see how colour-blind casting of a late-Medieval English knight might affect the story.

If you like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, also try: The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro (2015)

1688: Oroonoko

By Aphra Behn

There are a few reasons why this book from 1688 is significant. To start with, Aphra Behn is one of our first famous women writers in English. It’s also early in the history of the novel, so it can give readers a sense of the early novel as a form in English. And Oroonoko is a slave narrative, written in the early stages of England’s quest to become an imperial power.

It’s set in Surinam, in northern South America, and follows the life of the prince Oroonoko who is tricked into becoming a slave and later leads a slave rebellion.

History to her-story: The opera Imoinda moves the focus of the story to Oroonoko's great love.

The novel has relevance today as we think about movements like #BlackLivesMatter and about the importance of becoming familiar with black history. Behn is a white writer, however, and the text by now has been subjected to a range of analyses about how she as a writer at that time was dealing with race politics and the idea of slavery. It’s very reflective of its time so is not a story that goes uncriticised today.

But it is an early attempt to give her English audiences sympathetic African characters, and it’s a narrative that gives readers today a sense of an English writer grappling with questions of race and slavery.

Watch: Imoinda is a rewriting of Oroonoko into a libretto, the first to be written by an African Caribbean woman, Joan Anim-Addoi. It has been made into an opera by Cuban-born composer Odelane de la Martinez. The libretto moves the focus of the story from Oroonoko to his great love, Imoinda. You can see selected scenes from the opera on YouTube.

If you like Oroonoko, also try: Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup

1749: The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling

By Henry Fielding

Tom Jones, as it is often simply called, is an important and successful example of the English novel taking up the picaresque form, which was already famous in non-English novels such as the Spanish Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. The picaresque is a comic genre of novel that follows the adventures and misadventures of typically a low-born character, which Tom Jones is believed to be through most of the novel.

The novel is also famous for how it breaks out of its own story through an active, chatty narrator who comes in as you are following the hero’s adventures, and speaks directly to the reader throughout. The reader as a consequence develops a warm relationship with the narrator. This wasn’t the first book to use this kind of narrator, but it’s a very distinctive part of Fielding’s celebrated story.

Bawdy romp: Albert Finney stars as Tom Jones in the beloved 1963 movie version.

Even though it was written in the 18th century, Tom Jones has a freshness to it that modern readers can continue to enjoy. It’s a bit of romp, with a comic intelligence that speaks across time, and misadventures that readers today can identify with – he is a really likeable, memorable character who finds himself in all kinds of funny predicaments and just keeps pulling up.

There is a real pleasure in recognising that humanity in earlier characters, and seeing how people laughed at the things we still laugh at today.

Watch: The 1963 movie version Tom Jones, directed by Tony Richardson, has a very famous starring performance from Albert Finney. It’s a bawdy romp, and a beloved film. It’s a bit of a 1963 boysfest, but it is really enjoyable. The screenplay was by John Osborne, who wrote Look Back In Anger.

If you like The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling, also try: Moll Flanders, by Daniel Defoe.

1870s: Middlemarch

By George Eliot

This book is a thumper, and perfect if you want something to go the distance while you might be self-isolating.

Like TV shows such as Eastenders or Emmerdale today, named after the place in which the action takes place, what you have with Middlemarch is all the intertwined stories of the people in that town, in this case a fictional one in 19th-century England.

Middlemarch was originally serialised in 1871-1872 before becoming a novel, written by George Eliot, the nom de plume of a woman writer, Mary Ann Evans.

Middlemarch has a big cast of characters and the different chapters pursue their stories, and then you see them all intricately interwoven with each other, so at times it is quite gossipy and you get fantastically well-drawn characters.

And the characters stay with you – some of them really live in your mind beyond the novel.

It has soap-operatic dimensions to it: you follow characters through their bad marriages, falling in love with the wrong person, losing money and having professional catastrophes … Middlemarch needs a serious time investment but it is such a pleasurable read and so rewarding, and you get very absorbed in the small-town micropolitics of it all.

And the characters stay with you – some of them really live in your mind beyond the novel.

- House-bound shoppers trigger new online retail frenzy

- Five things you can do to protect your hearing at any age

Watch: Middlemarch is so sprawling, it’s hard for it to be captured in a film, but it was made into a 1994 BBC TV series. It was also updated and Americanised in a 2017 gender-bent, vlog-style webseries, Middlemarch: The Series, which you can check out on YouTube. It is the perfect kind of story for this era we are in of long-form TV, so I hope it gets made into a Netflix or HBO series!

If you like Middlemarch, also try: The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy.

1905: House of Mirth

By Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton is a fine observer of social convention; she was an American writer, looking particularly at upper-class society in New York, and House of Mirth brings us the character of Lily Bart, a refined, clever and complex woman brought up to wealth but at a stage in her life where she is economically vulnerable.

In an excruciating account, the novel traces her slow slide into increasing vulnerability and dependence on other people, particularly men.

House of Mirth is implicitly feminist in the way in which it shows us how a woman’s security is tied up in finding a relationship that can support her.

For all her personal resources – Lily Bart is bright, engaged and very beautiful – she is at 29 considered old for a single woman, and the rising panic the reader feels as she finds herself increasingly compromised and unmarried makes it an uncomfortable read. She is a heroine for whom we feel profound sympathy.

On the edge: Gillian Anderson as Lily Bart in the 2000 film version of House of Mirth.

Wharton has an extraordinary way of rendering the viciousness of polite society. She is a novelist of her time with a genuine eye for how society works, which is one of the reasons it is a great read for us today in societies that claim to be classless but actually have all these finely drawn lines and rules that everybody understands, but aren’t always spoken.

We are also living right now through a time where people are in incredible situations of precarity, and this is a very close and painful portrait of a person in precarity. The title certainly has an ironic ring to it.

Watch: Terence Davies’ 2000 film, starring Gillian Anderson as Lily Bart. Anderson is brilliant in it, and the movie does an excellent job of capturing her increasing isolation.

If you like House of Mirth, also try: The Wings of the Dove by Henry James.

1937: Their Eyes were Watching God

By Zora Neale Hurston

Part of a period called the Harlem Renaissance, this is a significant novel for giving us an African American woman’s voice from the 1930s.

It is Hurston’s most famous novel, about a southern woman called Janie Crawford whose family has a recent slave history – her grandmother was a freed slave – and which traces Janie’s life across three marriages and the complicated double oppression that she experiences as a black woman.

I have chosen this novel because after Oroonoko, it gives the sense of people, particularly women, living in the aftermath of slavery.

We are trying to understand those voices that have been left out and making sure we are listening.

It portrays the complex struggle for self-realisation on the part of a woman who is oppressed not just because of her race, but because of how she is treated by the men in her life.

It is an absorbing tracing of the complicated relationships between black men and black women in America, and also has a fantastic rendering of black speech so that the voices are very alive, and a moment in time is also brought alive.

This is a very relevant story for now, in the sense that we are trying to understand those voices that have been left out and making sure we are listening and exposing ourselves to them. It is also relevant given we are paying attention to sexual violence toward women (#MeToo) and to the violence visited on black people (#BlackLivesMatter), including our own Indigenous people, who are still living with the aftermath of colonisation.

Watch: Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Productions produced a telemovie in 2005 starring Halle Berry. Most people who read the novel tend to think the film has softened and mainstreamed the story to make it easier for a white audience to digest. It’s not a great film, but adaptations that are not good are still worth looking at because once people have read the book, they are in a position to see and analyse what has been done to the book. And in this case they might see how an adaptation might have ultimately backed away from some of the harder elements of the novel.

If you like Their Eyes Were Watching God, also try: The Color Purple by Alice Walker.

1980s: An Angel at my Table

By Janet Frame

The New Zealand author Janet Frame wrote her beautiful autobiography in three parts – To the Is-land (1982), An Angel at my Table (1984) and The Envoy from Mirror City (1984).

Frame is a writer with an amazing facility in English, who always has the right word for what she’s describing. Her writing is stunning. And this selection also shows how English as a literary language tells stories not just in the metropolises of London and New York, but branches out into all these other places, like rural New Zealand. It is also the particularity of her story that makes it special.

Frame is a writer with an amazing facility in English, who always has the right word for what she’s describing.

This autobiography is a real mid-20th century women writer’s story. It is heartbreaking but also tells an uplifting story on Frame’s path to becoming an author. It traces her early life through the poverty of her family in rural New Zealand and an appalling period where she was institutionalised for mental illness. She had crippling shyness and self-doubt, but with an incredible resolve underneath it all that kept her going, and kept her writing.

The three-part autobiography is available today in a single edition, An Angel at my Table, published by Penguin Books Australia.

Watch: My favourite Jane Campion film is 1990’s An Angel at My Table, starring Kerry Fox and the recipient of numerous awards, including second prize at the Venice Film Festival.

If you like An Angel at My Table, also try: Tirra Lirra by the River by Jessica Anderson

1997: The God of Small Things

By Arundhati Roy

This is one of those great big postcolonial novels by Indian writers that rightly came to people’s attention. The God of Small Things is a captivating, intergenerational family saga set in Kerala, southern India. It gives us a sweeping arc from the late 1960s to the 1990s, following fraternal twins Estha and Rahel through their early life into adulthood, and encompassing history, politics and a love story across the castes.

It is an incredibly rich rendering of the social and physical environment of southern India, and an example of how English literature opens itself up to all these different lives in different English-speaking communities. Roy even has characters in the novel who talk about English as the coloniser’s language, and the way in which the colonised have taken up this language and made it their own.

Sweeping canvas: The God of Small Things gives a rich rendering of the physical environment of Kerala in southern India.

Indian writers have a long tradition of long-form storytelling, and The God of Small Things exemplified what a number of Indian writers have been doing in English, which is, giving us a really big canvas of history and politics, but capturing it through the complexity and intimacy of a family.

And even if this is a totally new canvas to you, everyone can identify with the family dynamics and recognise the way in which the twins have an extraordinary connection with each other, and a special intimacy with their beautiful mother. The family dynamics are what hook you in and give you the grounding to orient you through that massive canvas. It is just so rich.

Watch: Arundhati Roy said in 2011 that she would never sell the film rights to The God of Small Things. A 2013 Pakistani TV series, Talkhiyaan, is based on the novel, but it’s difficult to find a subtitled version online.

If you like The God of Small Things, also try: A Fine Balance, by Rohinton Mistry.

2010: That Deadman Dance

By Kim Scott

Set in Western Australia in the early 19th century, the Miles Franklin Award-winning That Deadman Dance is a colonial encounter novel, looking back at a moment in Australia where things almost looked like they could go differently from how they went.

The protagonist is an indigenous boy called Bobby Wabalanginy, a mediator figure who is a link between his own Noongar community and the white newcomers with whom he is fascinated and forges quite positive – although not equal – relations.

The newcomers become quite dependent on Bobby and the Noongar, and the novel follows the mounting tensions between the colonisers and the indigenous people and how Bobby is ultimately placed in a difficult position between the communities.

Moment in history: That Deadman Dance author Kim Scott, whose novel portrays mounting tensions between the Indigenous and European communities. Photo: Pan Macmillan

This novel by Kim Scott, himself of Noongar ancestry, again fits into our thinking about the English novel as something that has made itself available to be taken up and changed and made to tell stories by people all across the English-speaking world, and stories that have taken us a long way from where English literature started.

And yet at the same time, when you think about Sir Gawain back in the 14th century, he was a mediator figure sent out by his community to deal with another community who then finds himself in a difficult position.

That sense of people trying to move between worlds, and trying to understand difference and foreignness and the way other communities’ rules operate, is an ongoing theme in literature.

These stories from throughout the centuries help us make sense of our own world today, when we are conscious of the way different communities interact, and who wins and who loses out of those interactions. That Deadman Dance is a very close-to-home exploration of that. It is part of that long story that literature tells.

Watch: To date there are no adaptations of That Deadman Dance.

If you like That Deadman Dance, also try: Taboo by Kim Scott

Louise D'Arcens is a Professor in the Department of English at Macquarie University