In recent weeks, uncertainty around the spread of COVID-19 has brought out the worst in many people – we’ve all seen footage of shoppers fighting over toilet paper in supermarkets. But we’ve also witnessed people doing remarkably selfless acts for those around them, whether friends or strangers.

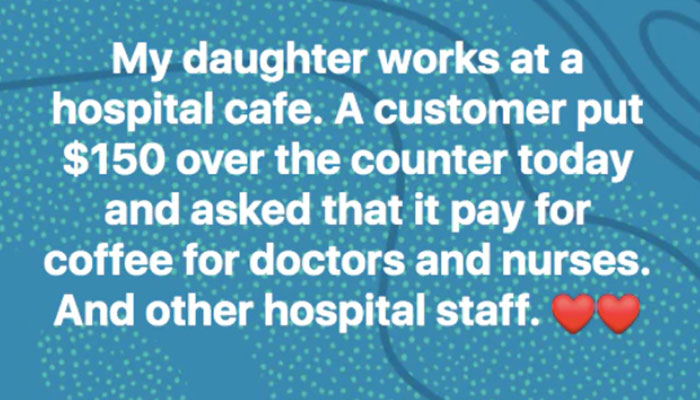

You need only jump on the recently launched (and already hugely popular) Kindness Pandemic Facebook page to be reminded of just how generous and thoughtful communities can be in times of crisis: stories emerge of people paying take-away meals forward in cafes, of others going out of their way to shop for elderly neighbours, of kids donating pocket money to friends in need, of shoppers delivering trolley-loads of pizzas to around-the-clock supermarket workers.

So why is it, exactly, that it takes a global pandemic for us to be nice to each other? Why can’t we do good deeds, all the time?

Professor Amanda Barnier from Macquarie University’s Department of Cognitive Science believes that actually, people are kind most of the time. “But perhaps when things are ‘normal’, our acts of kindness are unconscious – we take them for granted. When things slide out of normality, as they have recently, we not only pay more attention to these random acts of kindness, but also do them more often.”

When we’re in an unknown situation, like the current coronavirus pandemic, there are no mental shortcuts to take.

It’s our way, Barnier says, of grabbing the reins – of gaining some control in a situation that seems to be completely out of our control.

“Life is complex and fast moving, and people grasp whatever information they can and take meaning from that,” says Barnier. “Humans take mental shortcuts. It serves us well most of the time.”

These mental shortcuts, known by psychologists as ‘heuristics’, allow us to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. These rule-of-thumb strategies shorten decision-making times and allow us to function without constantly stopping to think about our next course of action.

An antidote to anxiety

Heuristics are great in situations we have experience in: deciding what to have for breakfast or which route to take to work. But when we’re in an unknown situation, like the current coronavirus pandemic, there are no mental shortcuts to take, and making rational decisions can seem overwhelming. “It can lead to feelings of anxiety,” says Barnier.

To mitigate the anxiety caused by our sense of a lack of control over the overall environment, Barnier suggests we pay more attention to the relatively smaller realms we can control: such as making someone else happy.

“Humans strive for meaning and a sense of control,” she says. “Naturally, we feel better when we’re in control, and some people can feel extremely anxious when we’re out of control. So in times like this, we should focus on what we can control. It gives us structure.

“When you do something nice for someone else you see – immediately – that you can be effective,” she says. “These acts of kindness we’re witnessing are one way to validate our sense of control and give us meaning. In making kind choices, we reassert who we are in the world and show we can still make a difference at a time when we are struggling to understand what we should be doing.

You’re now more likely to adhere to the social norms around you, rather than those demonstrated by, say, a celebrity.

"Being kind shows us that not everything is uncertain.”

This behaviour builds on the age-old notion that we do good to feel good when the world is ‘normal’. When times are great – when we’re in stable employment and have a clear plan for the future – our acts of kindness help us feel connected, part of a community, and in fact engaged in strengthening that very communal stability that buoys us.

Keeping us connected

This need for kindness to protect our collective integration “doesn’t stop when times are not so great", Barnier says. “Social isolation is bad for our mental health – being kind helps strengthen social connections. But above and beyond that, in bad times, it helps give us a sense of purpose” – a sense that circumstances might have otherwise robbed us of.

She adds that in times of chaos, kindness spreads more organically.

- Here's how to manage pandemic panic

- Retool and reboot: how to keep alfoat during times of economic crisis

“During uncertainty we tend to look to our peers for guidance and for emotional support, rather than those in high-profile positions. If someone in your group demonstrates values you admire, you’re now more likely to adopt and display thse values to adhere to the social norms around you, rather than those demonstrated by, say, a celebrity.”

Perhaps that’s why we are suddenly drawn to relatable, makeup-free, fellow-isolating versions of celebrities many of us are seeing now on social channels. Or maybe it’s why it’s so compelling to simply turn them off, and instead listen to a friend on Facetime relate small tales of grand hearts.

“It’s this kind of peer modelling that makes kindness so contagious during chaos,” Barnier says. And it’s these kindnesses that just might keep life with COVID-19 from spinning out of control.

Professor Amanda Barnier is Pro-Vice Chancellor (Research Performance) and Professor in the Department of Cognitive Science at Macquarie University.