Synaesthesia is an unusual phenomenon – not a disorder – where an ordinary stimulus, such as a sound, gives an extraordinary experience, such as a colour.

There are many different forms. The most common is grapheme-colour synaesthesia, where letters, numbers or words give an experience of colour and so, for instance, every time a person thinks about the letter A, they see a specific colour.

There are also cross-modal forms, such as auditory-visual synaesthesia. For most of us a sound is just an auditory event, but for an auditory-visual synaesthete, every time they hear that sound, they get a particular visual experience – which is usually colour – as well.

Colour is by far the most common evoked experience in synaesthesia; it occurs with seeing, hearing and touching, although we discovered when we were studying auditory-visual synaesthesia that it isn’t just colour they see. It is typically a coloured object, or a coloured moving line.

Some people report their synaesthesia helps with things, like “I am really good at maths because the colours help.”

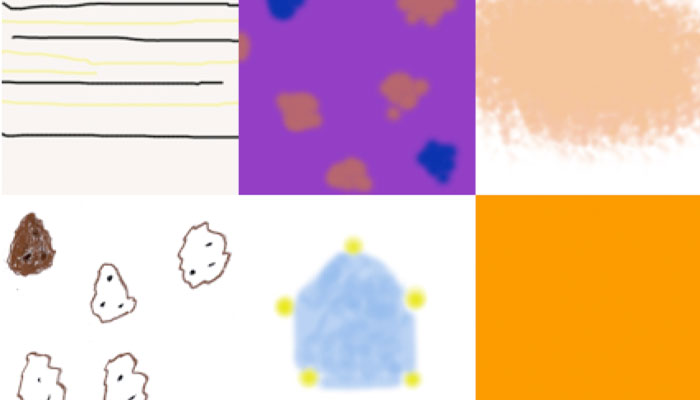

More rare cross-modal forms include lexical-gustatory synaesthesia, where people experience particular tastes when they hear or read certain words. Other people taste sounds, which we are exploring further, and we have previously studied olfactory synaesthesia, where every time you smell something, you get a particular visual image. In the laboratory, we get synaesthetes to illustrate their experiences while they smell different odours – like durian, after-shave, lemon, and so on.

Currently, one of my students is looking at mirror-touch synaesthesia, where people see someone being touched and feel it on their own body. This gives us a window into how the brain puts together information from vision and touch.

Not enough ‘points’ on the chicken!

Synaesthesia was documented as far back as 1880 by Sir Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin, but the renaissance in the field over the past two decades is mostly due to American neurologist Richard Cytowic, who in 1998 published a book, The Man Who Tasted Shapes, inspired by a synaesthete at a dinner party who reported that the chicken did not have enough ‘points’!

Unusual gift: Examples of pictures drawn by olfactory synaesthetes when they smelled a caramel odour, included in the Macquarie University research paper, Chocolate smells pink and stripy.

We still don’t really know why some people have synaesthesia – around 1 per cent of the population have it, and it is more common in females. There is a familial link, in that within families, more people will have synaesthesia than in the general population, but there are also many synaesthetes who don’t know of any others in their family. It doesn’t seem to convey any special talents, other than perhaps a benefit to memory and maybe creativity.

Some people report their synaesthesia helps with things, like “I am really good at maths because the colours help” but others say the opposite, like “I am really bad at maths because you can’t multiply colours!”

For most synaesthetes, though, it is just their normal way of experiencing the world, and they may even think the rest of us a bit weird!

From talking to more than 1000 synaesthetes during 20 years of research, there have only been a few for whom the synaesthesia became debilitating for various reasons – one had bidirectional synaesthesia, which is very unusual and tends to be more interfering due to sensory overload. Sounds gave colours, but colours also gave sounds; you can imagine that would be pretty overwhelming.

For most synaesthetes, though, it is just their normal way of experiencing the world, and they may even think the rest of us (non-synaesthetes) a bit weird! I usually describe it as an unusual gift, which gives people’s perception an additional richness. But it is as difficult for a synaesthete to imagine what it is like NOT to have it, as it is for us to imagine what it is like TO have it.

A unique window into how our brains work

Synaesthesia Research Group @ MQ is part of the Department of Cognitive Science. We are interested in learning more about synaesthesia as a phenomenon, but we also use it as a unique window into general cognition and how the brain integrates sensory information.

Colour codes: Evidence suggests the underlying mechanisms of synaesthesia are present in us all, but for synaesthetes, it goes to the point of conscious experience.

Our working hypothesis is that synaesthesia builds on mechanisms that we all have. For example, all of us (non-synaesthetes), if asked, tend to choose lighter colours as ‘going with’ higher-pitch tones, and darker colours for lower-pitch tones. There are similar patterns for size (higher pitch – smaller, lower – larger).

Synaesthetes’ experiences follow the same pattern: high-pitch tones tend to result in visual experiences that are light in colour, small in size and high up in space. This is some of the evidence that suggests the underlying mechanisms are present in us all, but for synaesthetes, it goes to the point of conscious experience; it is an extreme of human experience.

- Cheers to the quarantini as COVID-19 puts new zing in the lingo

- Aged care: an industry in crisis with plenty of blame to go around

My Honours work 20 years ago involved the first group study of synaesthetes using objective measures and it got a lot of media attention. After a radio interview, I had a call from a woman in her 80s who had kept her colours a secret for 70 years, because when she was a kid she had told her mum something about the green woman down the street, and her mum had said, “Don’t say that, that’s crazy talk, they’ll lock you up.” She was so amazed and relieved to hear on the radio that this was a thing called synaesthesia, and it wasn’t a disorder and other people did it. That was a really powerful experience, and is one of the reasons it’s so good to get the word out about synaesthesia!

As well as being a fascinating area, one of the things I really like about synaesthesia is that it reminds us of the inherent subjectivity of perception. What we see is always interpreted according to what we already know about the world - synaesthesia is a really nice reminder that, as Anaïs Nin said, we don’t see the world as it is, we see it as we are.

Dr Anina Rich is a Professor in the Department of Cognitive Science and Director of the Perception in Action Research Centre.

Learn more about how to participate in synaesthesia research at Macquarie University.