Early life stress such as neglect and sexual, physical and emotional abuse has long been associated with drug addiction and mental illness later in life.

Now, a comprehensive study led by Dr Sarah Baracz, from Macquarie University’s Department of Psychology, has linked drug abuse to changes caused by early life stress (ELS) in the body’s oxytocin system, which plays a pivotal role in the regulation of social behaviours and emotion.

Baracz is hoping that her research helps lay the groundwork for the effective treatment of drug addiction and its associated mental health issues in people dealing with the impacts of childhood trauma.

“I started my research career looking at oxytocin as a treatment for drug addiction, mainly for methylamphetamine methamphetamine (or ‘ice’), and trying to understand the brain circuitry that’s involved in the process,” Baracz says.

ELS is associated with a lot of mental health problems, not only heightened substance abuse but increased anxiety and depression.

“As I continued the research I became really interested in ELS and how it can follow you for your entire life and have such a big impact.

“ELS is associated with a lot of mental health problems, not only heightened substance abuse but increased anxiety and depression, behavioural problems like aggression, some cognitive changes, and cardiovascular and physical health changes such as obesity, so ELS seems to affect a wide spectrum of issues.”

In Australia, a conservative estimate of 49,000 children were victims of maltreatment in 2016-2017 alone, according to figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rates of maltreatment typically are highest during the first four years of a child’s life.

How childhood trauma changes the brain

Baracz says that researchers first reported in 2010 the connection between ELS and changes in how the oxytocin system worked in people who had experienced it. Essentially, the system becomes dysregulated, affecting its many functions including regulation of stress and emotion.

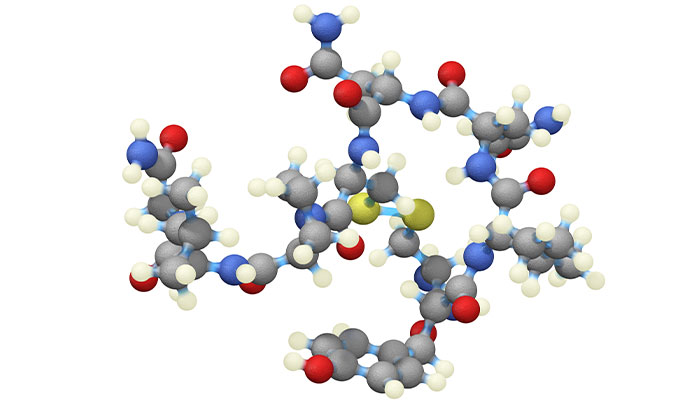

Because clinical trials in humans can provide only limited information of how oxytocin, a neuropeptide, is working in the human brain, researchers have relied on pre-clinical animal models. This has allowed them to see via the brain tissue of rodents subject to ELS the changes in how the oxytocin system works.

“Our review basically sums up all of the published literature, which shows that ELS exposure seems to be changing how many receptors in the brain are available for oxytocin to bind to; also, changes in the number of cells which produce oxytocin have been reported,” Baracz explains.

Because oxytocin is so important for normal social behaviours, it has been used in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia.

“Because oxytocin is so important for normal social behaviours, it has been used in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia to try and treat the social deficits that are experienced, and there are also some clinical trials looking at oxytocin to treat cocaine, alcohol and nicotine dependence.

In ongoing clinical trials, oxytocin is being administered using a nasal spray.

“But what we have found is that oxytocin isn’t always a good treatment option, and it doesn’t always seem to reduce particular symptoms in people, so there is a theory that using oxytocin as a treatment would be more beneficial for people who have an oxytocin system that isn’t functioning optimally, because you want to try and get the system back to its normal functioning.”

Teen years could be key treatment time

Baracz has been conducting her own pre-clinical research and, in findings submitted for publication, has found that oxytocin treatment during adolescence reduces the depressive-like symptoms and methamphetamine-seeking behaviours of ELS-affected rats in their adulthood.

“My research is being focused on treating the animal after the ELS because it is hard to identify people who are currently experiencing it because child abuse often goes under-reported,” Baracz says.

“At the moment, the data is really promising. It really suggests that adolescence is a good time to treat these animals to reduce the detrimental impact that ELS has on later life vulnerability for drug abuse and for depression.

While the period between pre-clinical data demonstrating the effectiveness of a drug and clinical trials in humans is usually at least 10 years, Baracz is optimistic that the time frame in this case could be reduced.

“Considering oxytocin is already being used in clinical trials, having some pre-clinical data published that it could be used as a treatment for this particular population could mean clinical trials start earlier,” Baracz says.

“ELS is such a big problem, and it’s something we really need to address, to see if we can help improve those individuals’ lives because ELS can completely ruin them.”

Dr Sarah Baracz is a lecturer in the Department of Psychology.