After weeks of trial and error, and teaching herself how to sew, Macquarie scientist Julianna Kadar at last landed on the best way to attach ‘Fitbits’ to Port Jackson sharks.

The little dog harnesses, modified to fit snugly on sharks yet not hinder their movement, were the key to collecting world-first data on the secret lives of Port Jackson sharks.

Each winter for three years, Kadar and her colleagues from Macquarie University’s Fish Lab and research partner Taronga Zoo, captured Port Jackson sharks from the wild and fitted them with acoustic accelerometers which, like Fitbits worn by humans, collect detailed information on the sharks’ movements.

During the migratory sharks’ winter breeding season, the scientists would boat out into Sydney Harbour, don scuba gear, and grab 10 sharks to take back to Taronga Zoo for monitoring, by video as well as with the ‘Fitbits’, before releasing them after seven weeks and collecting another group of 10 sharks to monitor.

There are thought to be tens of thousands of Port Jackson sharks down the east coast of Australia from the NSW-Queensland border and around the southern coastline to Perth. The Fish Lab conducts Port Jackson shark research in Jervis Bay in southern NSW as well as Sydney Harbour and Port Stephens, where the sharks reproduce during winter before migrating south to Tasmania, leaving thousands of their corkscrew-patterned, seaweed-like eggs behind, wedged in crevices and rocks and sometimes washed up on beaches.

It’s incredibly difficult to study sharks in the open ocean and modern technology is leading to new frontiers in behaviour observation that were not possible just a couple of decades ago.

The data collected confirmed “beyond a doubt” that Port Jackson sharks are nocturnal with their activity peaking just before midnight and decreasing before sunrise. The study also showed that zoo-based sharks displayed similar daily activity patterns to those in the wild.

But that was not the most exciting finding, says Kadar, the lead author of a study published in July in the Journal of Ecology and Evolution.

“It was thought before that they were nocturnal, so we were looking at environmental factors as well, what actually makes them move, and what makes them migrate.

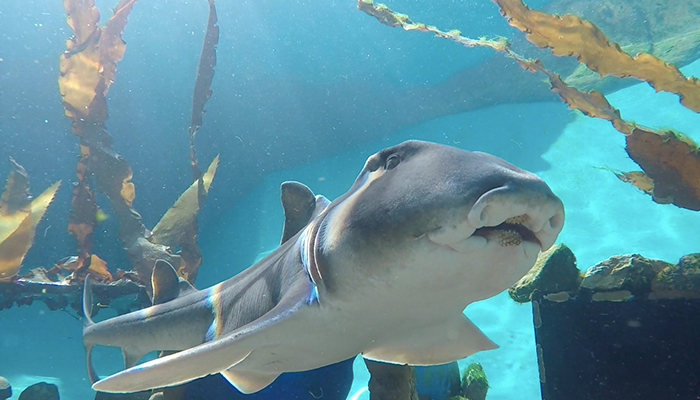

Deep dive: The 'Fitbits' collected detailed information on the sharks’ movements. Picture credit: Julianna Kadar.

“We found that sex, time of day, and sex-specific seasonal behaviour all influenced the sharks’ activity levels. In other words, males and females were both more active at night and when comparing early and late breeding season, we saw differences in the sexes.

“And it turns out the males, during late breeding season at night, are most active, and we think that’s because they’re preparing to migrate, basically. This also fits with what we know already about their migratory behaviour.”

This is the first time signs of migratory restlessness have been recorded in sharks of any species, and while Kadar says it is a preliminary finding only, it is a significant one.

- Bright idea: Lights under boards may hide surfers from sharks

- Wetsuits that hide humans from sharks

- Too much dash tech a dangerous distraction

The research also suggested that male sharks head south before the females, possibly, says Kadar, because the females stay behind to keep laying eggs that have a better chance of survival because less sharks are around to eat them.

“We need more sharks and more data to confirm this, but it is really interesting that zoo-based males in late breeding season were displaying the highest activity levels,” Kadar says.

“We saw the males leaving in the wild and saw the zoo-based males elevate their activity at the same time.”

“There have been other studies with salmon and eel species, and this phenomenon is commonly seen in birds, that show anxious behaviour with higher activity levels when it’s time to migrate, but it’s never been seen in sharks before.”

Leading to new frontiers in behaviour observation

Head of the Macquarie Fish Lab and co-author of the study, Professor Culum Brown, says the study confirms that the tagging technology used is a promising method to determine activity patterns of marine species.

The tags can record movements for up to a year and provide detailed information on where sharks go, and when.

“It’s incredibly difficult to study sharks in the open ocean and modern technology is leading to new frontiers in behaviour observation that were not possible just a couple of decades ago,” he says.

But first, there was the issue of how to attach the sensors to the creatures in a way that would guarantee effective collection of data. The harnesses containing the devices had to be just right - too wobbly an attachment would impact on the quality of the data; too tight-fitting and the regular activity of the sharks could be affected.

Testing new tech: Macquarie scientist Julianna Kadar (pictured left) modified dog harnesses in order to attach Fitbits to the Port Jackson sharks.

“We had to go through a lot of trials to make the perfect fit for the animal and ensure that the sharks were comfortable,” Kadar says.

“I made a lot of different harnesses - I even learned how to sew – and basically the ones that ended up being the most successful, because we tried wetsuit material and a soft spandex material, were these little adapted dog harnesses which didn’t seem to inhibit them for the number of days it was attached.

“Then it was quite a challenge, to figure out a way to put them on the actual shark, just because they do have an interesting shape and their dorsal fin is detached at the back.”

Ultimately the harnesses would take about five minutes to attach – speed was crucial to minimise the effects of the tagging process on the sharks’ behaviour. The sharks would also be kept in the water during the tagging, “because even though they are known as a hardy species, their organs and bodies have never experienced out-of-water gravity so it’s best to avoid that,” Kadar says.

Sharks are actually social species

Kadar’s study is the latest in a raft of research by the Fish Lab, part of Macquarie’s Department of Biological Sciences, into Port Jackson sharks.

Popularly considered lazy because Sydneysiders often spot the bottom-dwellers resting in the shallows of bays and beaches, Culum Brown established through tagging that the sharks were actually migrating about a thousand kilometres to spend warmer months in Tasmania, an impressive distance for a creature no more than a metre and a half long. (During Kadar’s study, the scientists made sure to release the Port Jackson sharks from Taronga Zoo in time for them to make the migration.)

Fish Lab research has also shown that the sharks have individual personalities and social networks, ‘hanging out’ for years with the same group of sharks of similar age and the same sex.

Fish are friends: The research discovered that sharks have individual personalities and social networks. Picture credit: Catarina Vila Pouca.

Kadar says understanding the baseline behaviours of a species like the Port Jackson shark, which has a key role in the ecosystem, is crucial because changes in that behaviour are one of the first warnings that the environment is changing.

“The sharks are affecting the environment when they come into these bays – for example they eat a lot of urchins, and urchins eat kelp, so if there were to be a reduction in the number of Port Jacksons, there would be more urchins, then a lot less kelp, then less habitat for other creatures, so there would be cascading environmental effects.”

“In addition to that, we think they are functioning as nutrition-transfer mechanisms – they spend all their time down south and we think they are feeding down there, and then they come up into our harbours and bays in winter and they’re laying thousands upon thousands of eggs, and those are feeding the animals up here in Sydney Harbour, Port Stephens and Jervis Bay, so we think they are having quite an important effect on the environment.”