Not many people are aware that mainland Australia has an active volcanic region that could erupt again anytime.

What lies beneath?: A view of blue lake volcanic crater at Mount Gambier in South Australia.

So Macquarie researchers are studying the volcanic rocks from these volcanoes to understand how much warning time we might have before an eruption and develop an emergency response plan similar to New Zealand.

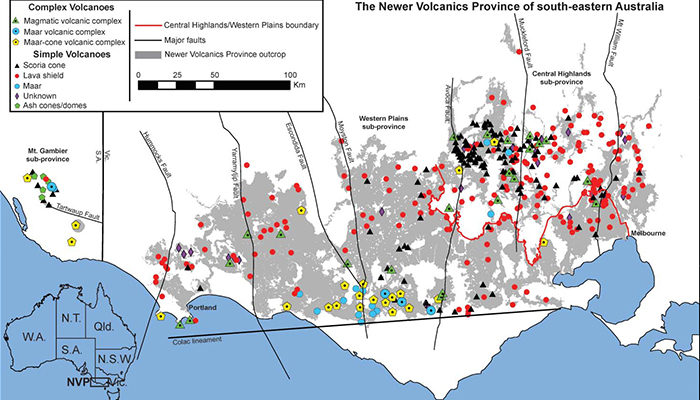

Mount Gambier, South Australia, was the last Australian volcano to erupt around 5,000 years ago. It’s located in the Newer Volcanics Province, an area stretching east more than 400 kilometres from Mount Gambier to Melbourne. This area covers over 23,000 square kilometres, contains over 400 volcanoes and holds Australia’s youngest volcanoes.

Volcanoes are classified as “active” if they erupted less than 10,000 years ago and are likely to erupt again, says Associate Professor Heather Handley, a volcanologist from Macquarie’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

There’s no need for panic but we need to develop eruption scenarios and have a response plan.

Eruptions in the Newer Volcanic Province occurred between 4.5 million and five thousand years ago. “We don’t really know when the next eruption is going to be,” says Handley. “But it could be any time.”

Handley and her team are analysing the chemistry of crystals in the erupted rocks collected from the volcanic site, to determine how fast they came up to the earth’s surface from their source, likely around 60-90 kilometres underground. She compares her research to analysing rings on a tree trunk.

Fault line: This map shows the location of the Newer Volcanics Province, including the extent of lava flows and the different types of volcanoes. Picture credit: Julie Boyce 2013.

“Based on the thickness of the tree rings, you can find out about the environment the tree was growing in, the rainfall or temperature variations,” she says.

Making future predictions

“It’s the same with volcanic crystals. They record the history of their journey. We work out from chemical changes in the crystals in the rock how fast that molten rock moved from the source to the surface.”

Looking at thin volcanic rock slices under a microscope, Handley searches for patterns which signify chemical changes in the rock’s crystals. One of the clues is that the rocks are embedded with chunks of the mantle that stayed intact as it travelled to the surface and didn’t have time to melt or settle out due to their greater density.

“The presence of these mantle fragments suggests that the magma moved very fast to the surface – possibly in a matter of days,” she says. “We are trying to understand more about the magma plumbing systems underneath these volcanoes by looking at how magma interacts with these fragments. Looking at past volcanoes helps us predict future activity.”

Far-reaching impact: Handley says her research could be used by the government to form a regional eruption response plan.

Volcanoes can also erupt individually or in groups. “If there are clustered eruptions we might get several within a short geological time frame and then a long period of nothing for tens of thousands of years, and then another pulse of activity. Then it's quiet again,” she says. “So we hope to determine the ages of more of the volcanoes in the field and then have a better handle on the periodicity of the eruptions.”

Researchers at Monash University have discovered that the eruption of Mount Gambier was also quite large - comparable in size to the eruption at Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland in 2010 that threw volcanic ash 5-10 kilometres into the air and closed European airspace for a week. This eruption was rated at a Volcanic Explosion Index of 4.

- The story behind the journey of the black bean tree

- Cites need more rooftop gardens to balance urban sprawl

“A similar-sized eruption in Australia would mean ash could affect Melbourne, Sydney, the east of Australia and possibly Auckland,” Handley says. “I think we need to take this potential volcanic activity a little bit more seriously and prepare for it. It is a very low probability but high-risk event.”

Disaster response plan needed

Handley is hoping her research will inform the government so that it can create regional eruption response plans - similar to Auckland’s. The New Zealand city has a comparable but smaller active volcanic field containing about 53 volcanoes. The last one erupted 600 years ago at Rangitoto Island. Auckland’s Volcanic Field Contingency Plan details how emergency services, the army and local councils would react.

“It’s worth considering the associated hazards of a volcanic eruption in the Newer Volcanics Province too,” she says. “If it happened during dry periods it could cause a bushfire. If it occurred near the coast offshore it could trigger a tsunami.

“There’s no need for panic but we need to develop eruption scenarios and have a response plan. It’s just not worth laughing and saying: ‘it could never happen here’.”

Heather Handley is an Associate Professor in Volcanology and Geochemistry at Macquarie University.