Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this story contains images and names of deceased persons.

The remarkable story of a forgotten Australian hero has been rediscovered and told anew in a feature documentary by Macquarie University film-maker Associate Professor Tom Murray.

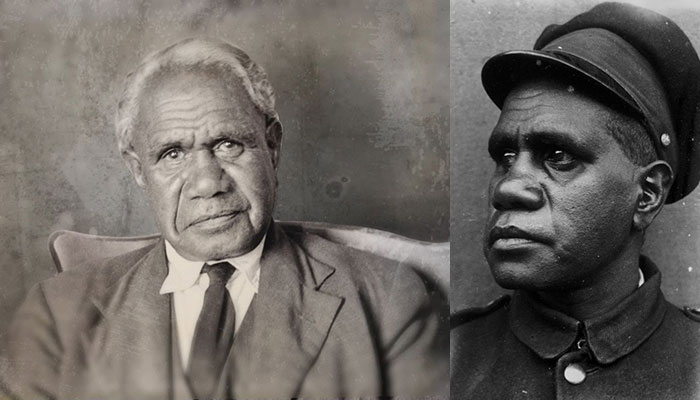

Douglas Grant, orphaned in a Frontier Wars massacre in Far North Queensland in 1887 and subsequently fostered by a Scottish immigrant couple, was a World War I hero, an outspoken advocate for the rights of Aboriginal people and, says Murray, a ‘bridge builder’ between black and white Australia.

As well as a soldier and journalist, he was a reader of Shakespeare and a bagpipe player who could put on a fine Scottish brogue. During his lifetime, he was famous – not least for being the only non-commissioned Aboriginal officer in the Australian Imperial Force, and a German prisoner of war who sparked the avid curiosity of his captors.

It is truly remarkable that we don’t know about him – and not just the broader Australian population, but most Aboriginal people don’t know about Douglas Grant either.

Now, The Skin of Others – set for limited cinema release and broadcast screening on SBS later this year following its debut at the 2020 Sydney Film Festival – reveals Douglas Grant for new generations.

“This is a really courageous, brave, incredibly intelligent, thoughtful man we all should know about,” says Murray. “Throughout his life he was trying to reconcile our history, which has its very tragic elements if you are an Aboriginal person, and to inspire a more inclusive future.

“He didn’t give up on Australia as he saw it.”

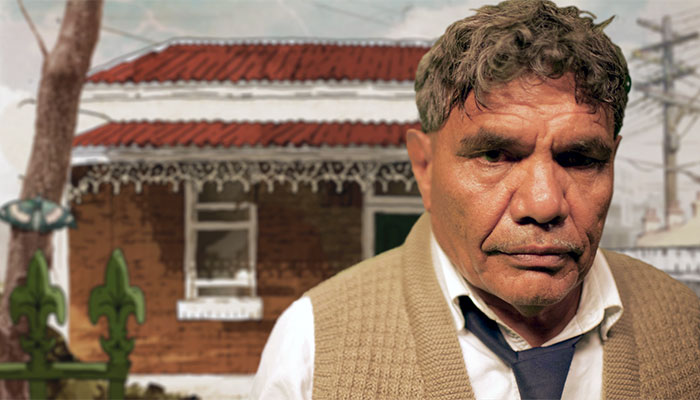

Two worlds: Balang T. E. Lewis as Douglas Grant, against the backdrop of a re-creation of Henry Lawson's North Sydney home.

Imagine, says Murray, a man who goes to war, becomes a hero for his actions – including being the principal advocate and lobbyist for the needs of fellow prisoners of war in German camps – and then upon his return in the 1920s writes popular journalism about the plight of Aboriginal people.

In reaction to the 1928 Coniston massacre in the Northern Territory, he writes a damning piece in a major Sunday newspaper condemning the violence against Aboriginal people, putting his life in danger, says Murray, given the forces aligned at the time against Aboriginal people speaking up.

“It is truly remarkable that we don’t know about him – and not just the broader Australian population, but most Aboriginal people don’t know about Douglas Grant either,” Murray says.

“As historian John Maynard says in the film, he should be an inspiration for Indigenous people, because we need more Aboriginal heroes.”

In search of the holy grail

Murray, an ARC Future Fellow whose previous documentaries have won accolades including selection in the Sundance Film Festival, came across Grant’s story in 2011 in archival newspaper articles and in a 1960s book about Reg Saunders, another heroic Aboriginal soldier.

Bridge-builder: Indigenous activist Douglas Grant in the 1940s, and in 1918 as an Australian Imperial Forces soldier.

“The book was called The Embarrassing Australian: The Story of an Aboriginal Warrior, and in it there was this tantalising piece of information about Douglas Grant: that he had been captured on the Western Front in World War I and studied as part of a German social-science experiment,” Murray recalls.

“Straight away I knew I had to go to Berlin and look through the archive relating to this war-time experiment.

“My holy grail was to find moving pictures of Douglas Grant, and to hear his voice … alas I got neither of those two in the end, but I got pretty close.”

But the making of the documentary over nearly 10 years delivered other, profound rewards.

A film-maker finds his guide

The acclaimed actor Balang T. E. Lewis – who launched his career playing Jimmie Blacksmith in Fred Schepisi’s 1978 film The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith – came on board to play Douglas Grant in 2015, a few years into Murray’s project.

Power and passion: Associate Professor Tom Murray with his friend and collaborator Balang T. E. Lewis.

Max Cullen also makes a guest appearance as Henry Lawson, whom Grant met in 1921 shortly before Lawson’s death; the scenes of their meeting were filmed in a Macquarie University production studio, where Lawson’s North Sydney home was re-created.

Lewis, Murray says, became his guide in the film, which consequently developed into a story about Lewis as well as Grant, about Australia’s violent colonial history, and about the vision held by both these ‘bridge builders’ of a more reconciled and inclusive Australian future. (Ballad of the Bridge-Builders, a song co-composed by Murray and performed by Archie Roach in the film, won best original song composed for the screen at the 2020 APRA Awards.)

“To be given that role just about made [Lewis] cry, given his own life, which he felt was between two worlds in the sense that he has an Aboriginal mother from the Gulf Country in Arnhem Land, and a white stockman father, so he felt his own life mirrored some aspects of Douglas Grant’s life,” Murray says.

To lose a friend and to lose such a powerful and passionate collaborator was doubly devastating.

Tragically, the collaboration was cut short with Balang Lewis’s sudden death in 2018 before filming was complete. The Murrungun man’s portrayal of Douglas Grant was the last major role of the beloved and iconic actor, songwriter and singer.

“It was really tough, because we had become pretty close over a bunch of years, so to lose a friend and to lose such a powerful and passionate collaborator was doubly devastating,” Murray says.

- Stress-busting tips for HSC students facing lockdown learning

- Inside the Australia-UK trade deal: who benefits most?

“Balang Lewis was one of those incredibly curious people who delights in finding things out – he was totally passionate that through art and an understanding of Country, we are all going to be better people.

“This was another story among many that Balang has pushed forward over the course of an incredible career, just to try to get people to understand some of those values that were incredibly dear to him.”

Taking the film out into the world with Lewis, Murray says, “would’ve been a lot of fun”.

The heavy toll of war and speaking out

Douglas Grant’s foster parents Elizabeth and Robert Grant, a taxidermist at the Australian Museum, were good people, says Murray, who really loved Douglas and did their best for him, including giving him a good education.

Well loved: Douglas Grant with his foster parents Elizabeth and Robert Grant and foster brother Henry.

They had both died by the early 1920s, before Grant spent nearly 10 years at Sydney’s Callan Park Mental Hospital following a breakdown in 1931. He had already been in two wars by that time, Murray points out: Australia’s Frontier Wars and World War I.

“Like a lot of returned soldiers in the 1920s, he would have suffered from PTSD and self-medication with alcohol was what a lot of the men did at that point,” Murray says. “Also the stress he was under as an Aboriginal activist writing in national newspapers about the plight of Aboriginal people – it’s a fair assumption that he would have attracted the interest of police and government authorities who probably watched him.

“Police intimidation for speaking out was a known fact of being an Aboriginal activist in the 1920s; there is every reason to think that was happening to Douglas Grant as well.”

Grant died in 1951 at a war veterans’ home in La Perouse. In his final years he had reportedly told a fellow former solider, heartbreakingly: “I’ve lived long enough to see that I don’t belong anywhere, and they don’t want me.”

Seventy years later, says Murray: “The Skin of Others is about truth telling and history, and trying to seek a better agreement for the future of this country.

“And I think Douglas Grant is a national hero.”

Associate Professor Tom Murray is an ARC Future Fellow in the Department of Media, Communications, Creative Arts, Language and Literature.