It's a sight you'd expect to see in the smog-choked cities of Delhi or Beijing — but growing numbers of people can be seen wearing pollution masks on Sydney's streets after weeks of bushfire smoke.

Smokey skyline: Ferry services have been suspended, flights delayed and workers evacuated from their offices after bushfire smoke set off building fire alarms.

Particles in the air can pose a significant health risk — bushfire smoke has complex chemistry depending on what is being burnt but they contain an array of pollutants, some of which are carcinogenic even at relatively moderate concentrations.

Wildfire smoke is characterised by an abundance of tiny particles that are dominated by soil and carbon – that are less than 2.5 µm (there are 1000 µm in a millimetre) – gases and water vapour.

The key indicator for risk is the concentration of 2.5 µm (PM2.5) because research shows there is no safe level of exposure to this particulate matter. Higher short-term (acute) exposures pose a greater risk, especially for those who have respiratory and/or cardiovascular disease.

The NSW Government’s Air Quality Index (AQI) shows that about two-thirds of the sites being monitored recorded daily PM2.5 levels (25 µg/m3 per 24 hours) above the national standard this week. The worst affected area is the Hunter, due to a variety of sources including woodsmoke.

Short-term exposure can trigger asthma, and cause wheezing and breathing difficulties, leading to a rise in ambulance call-outs and people presenting at emergency departments.

Recent levels seen in Sydney are significantly higher than the previous highest recorded maximum daily PM2.5 concentration (of 123.8 µg/m3) which occurred at Richmond on 25 April 2018, following hazard reduction burns in the Sydney area.

PM2.5 can penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream, causing respiratory problems. Short-term exposure can trigger asthma, and cause wheezing and breathing difficulties, leading to a rise in ambulance call-outs and people presenting at emergency departments. Even if you don't have asthma, you may still suffer from a sore throat, cough or runny nose.

Smoke pollution is particularly concerning for the elderly, people with pre-existing respiratory conditions and children, who breathe more air per kilogram of body mass than adults.

Safety precaution: P2 masks are the only ones that can filter out a meaningful level of air pollution, so long as they fit properly, warn Taylor and Isley.

Adverse long-term health effects from the current smokey atmosphere are not well described but emerging evidence suggests that they are cumulative over a lifetime, with outcomes being dependent on future exposures.

- Digging up the dirt: are your home-grown vegies safe to eat?

- Can we predict when a volcano will erupt?

- World-first findings pinpoint where and when sharks are more likely to attack

Other pollutant exposures during wildfires include the release of trace metals from trees that have been exposed over their lifetime. Our previous research of wildfires has shown that industrial lead from gasoline use is re-released into the environment from ashed Australian trees.

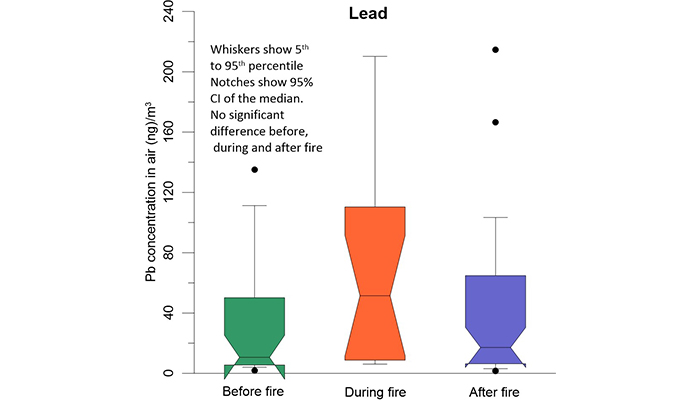

It has also been speculated that these metals are released into the air posing an increased health risk from toxic metals. In order to assess the potential burden of re-released industrial metals on air quality during wildfires, we studied four major bushfires in 1994, 1997, 2002 and 2004. Surprisingly, we found that concentrations of metals and other elements in Sydney's air (lead, aluminium, arsenic, cadmium, calcium, cobalt, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, titanium and zinc) were not significantly different before, during and after the fires.

No major impact: A graph from Taylor and Isley's research showing the concentrations of lead before, during and after four wildfires between 1994-2004.

There are several measures people can take to help protect their health in the short-term, such as using any prescribed relieving medications and seeking medical advice if symptoms do not improve.

For those who own an air conditioner, it may be appropriate to use it on air recirculation mode as long as the fresh air intake is closed and the filter is clean, preventing particles from being drawn into the home. Obviously, if the air pollutants have leaked into your home, which is now the case for some people, this intervention action might not help. In this case, buying and running a suitably sized high-efficiency particulate air filter (HEPA) would be the most preferable option.

With hot and dry conditions set to continue over the summer, health officials warn there's more to come, making it strongly advisable to monitor the air quality via the NSW Government's real-time updates, and read and follow their health advisory.

- Professor Mark Patrick Taylor and Dr Cynthia Faye Isley are from the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Macquarie University. Their research focuses on environmental pollution and risks to human health.