A Macquarie University study of media reports of boxing deaths in Australia between 1832 and 2020 has revealed a worrying truth: the regulations that govern the sport are not giving fighters enough protection.

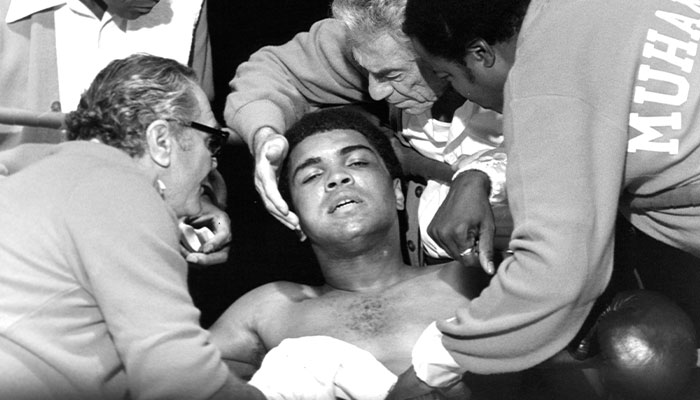

Fatalities: If boxers are still dying, then the government regulations are not achieving what they were meant to, says Dr Lystad.

Between 1832 and 2020, 122 professional and 40 amateur boxers died in Australia, with 74 per cent of these deaths attributed to traumatic brain injury. All were male, with the youngest aged just 15.

While some deaths occurred in the ring, most happened during the hours and days following the incident, with 96 per cent occurring within a week.

Deaths were more frequent between 1910 and 1930, but 11 men died after government regulations to improve safety were introduced in the mid-1970s.

One big area for improvement is the threshold at which officials step in to stop a fight if one of the competitors looks visibly dazed.

Ten out of these 11 recent deaths were attributed to traumatic brain injury, and two of these fighters were only 18 when they died.

Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation Dr Reidar Lystad says the most recent boxing death in Australia was in 2019. Professional fighter Dwight Ritchie, 27, collapsed and died in November of that year after a punch to the body during a routine training session in Melbourne.

“If athletes are still dying, then the government regulations are not achieving what they were meant to,” says Lystad, an injury epidemiologist.

“An estimated 300,000 people take part in some sort of boxing-related activity in Australia every year, ranging from non-contact boxercise to the elite level.

“Medical associations around the world, including the Australian Medical Association, have called for boxing and other combat sports to be banned, and that understandably raises the ire of the boxing community.

“Even without changes to the competition rules, though, safety could be improved for fighters if the government regulations were better designed and administered.

“One big area for improvement is the threshold at which officials step in to stop a fight if one of the competitors looks visibly dazed. If matches were stopped earlier, it would limit the danger to the athletes."

Video analysis of 60 professional boxing and mixed martial arts matches in the US found that 40 per cent should have been stopped earlier than they were, Lystad says.

Concussion education

Other important areas for improvement include mandatory concussion education for athletes, coaches, referees and ringside physicians, and mandatory reporting of concussion, as without this data there is no way to evaluate the impact of any regulatory changes.

Long-term dangers: It's suggested that Muhammad Ali may have taken close to 200,000 impacts to the head during his career.

Another area of concern is the regulatory variations across states and territories, including there being no regulations in place for boxing in the Northern Territory or Queensland.

The siloed approach to regulation across jurisdictions can potentially enable fighters who have their licence denied or suspended in one jurisdiction to simply travel across state borders to compete. Athletes would benefit from a unified approach to regulations across jurisdictions, Lystad says.

Most people think of the ‘danger zone’ as being the match, but sparring sessions can be dangerous too. Of the six most recent deaths, half were related to injuries sustained in training.

Some coaches, including those who work with boxers too young to compete, think you can condition the brain to deal with blows.

And worrying as the death statistics are, dying during or immediately after a fight is not the only concern for boxers.

Combat sports like boxing, and contact sports like NRL and AFL, pose a risk to their athletes because they sustain repeated heavy blows to the head. A single blow can result in concussion, a type of traumatic brain injury typified by headache, dizziness, confusion, nausea and vomiting.

The long-term consequences are more concerning.

Tens of thousands of hits

“Many people don’t realise that sustaining blow after blow to the head has a cumulative effect,” Lystad says.

“Over the course of a career, boxers are hit in the head tens of thousands of times, and most of these occur while sparring. Muhammad Ali reportedly estimated that he took about 29,000 head impacts during his boxing career, but others have suggested the true number may be closer to 200,000.

Warning: Dr Reidar Lystad (pictured) says brain cells do not get stronger with repeated blows; instead they eventually wither away.

“Some coaches, including those who work with boxers too young to compete, think you can condition the brain to deal with blows.

“That’s not how the brain works, though. Brain cells don’t get stronger with repeated blows, instead they stop functioning properly and eventually wither away.”

These repeated blows to the head can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which has symptoms similar to dementia: confusion, difficulty in thinking, behavioural problems and mood disturbance. It can ultimately result in death.

Many famous boxers, like Sugar Ray Robinson and Leon Spinks, have shown signs of decline in the years before their deaths.

Lystand says CTE can sneak up on boxers due to the lack of ongoing monitoring of brain health.

“All fighters must undergo a medical check before being registered to compete, but if they were monitored using standardised testing over time, it would be easier to spot when they were starting to decline and should retire,” he says.

Dr Reidar Lystad is a Research Fellow at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation and a member of Macquarie University’s Concussion and Repetitive Head Trauma Research Group.