When it comes to major infrastructure projects, poor planning often leads to delays, budget blowouts and other inefficiencies, reflecting a growing need for project managers to improve the accuracy of schedules and completion dates.

Planning flaws: Project managers often underestimate the cost and length of time it will take to complete a major capital works project, the researchers say.

Dr Matej Lorko, Professor Maroš Servátka and Dr Le Zhang from Macquarie Business School say there is a high failure rate in many infrastructure works, and that project managers need to learn how to improve the accuracy of estimation times if they are to avoid costly errors.

“Poor planning leads to delays, additional costs and other inefficiencies. And sometimes the project does not even get completed,” Servátka says.

He says delays in one project can slow down the progress of others that run in parallel or sequentially. This can result in ballooning costs and reduced lower efficiency for the entire organisation.

Overly optimistic

Servátka says planners can avoid project failures by relying less on overly optimistic schedules.

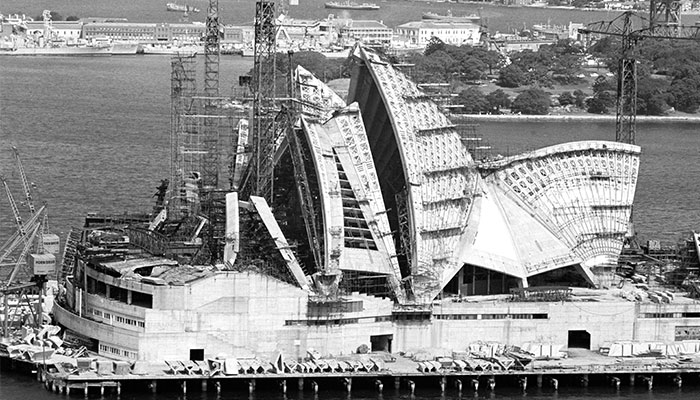

Nothing new: Project overruns have a history – the Sydney Opera House was delivered 10 years late and $95 million over budget.

Project managers often underestimate the cost and length of time it will take to complete a major capital works project. In NSW, recent examples include the proposed northern Beaches Link motorway tunnel, the 9km NorthConnex tunnel and the Pacific Highway upgrade.

The Beaches Link had its completion deadline extended by about two years with the $14 billion project now likely to be finished by 2027-28 and NorthConnex was a year late as equipment and software tests delayed the opening. In December 2020, the last section of the Pacific Highway dual carriageway was completed – 24 years after the project started.

There are numerous examples of major infrastructure projects that were delayed or never completed.

The academic research, Improving the Accuracy of Project Schedules (published in the journal Production and Operations Management), says a common feature of virtually all business projects is the uncertainty regarding the amount of time and resources needed to deliver on time and within budget.

“Proficient planning processes capable of generating adequate project plans are essential for executing a cost‐benefit analysis and deciding which projects to initiate,” the paper says. “Once a project is underway, a realistic project schedule is a crucial determinant of project success, ensuring effective allocation and utilisation of resources in an organisation.”

- Facebook is selling our data: are there laws to protect it?

- Why we can't get enough of Anne Boleyn: new book

There are numerous examples of major infrastructure projects that were delayed or never completed such as the abandoned City Circle railway tunnels in Sydney, or the 100-year wait for the southern spires to be installed at St Mary’s Cathedral in the CBD in 2000.

Project delays and cost overruns are nothing new. Most famously, the Sydney Opera House was delivered in a scaled-down version 10 years late in 1973 at a cost of $102 million (unadjusted for inflation) instead of the planned $7 million.

Manage expectations

One way of improving the accuracy of completion times is by managing client expectations, steering clear of guesstimates and avoiding a definitive deadline.

Critical detail: Professor Maroš Servátka (pictured) says providing feedback to planners upon the completion of a project is vital.

“A much more promising approach is providing historical information about the duration of similar projects completed in the past," Servátka says.

"This is important because planners seem to suffer from the so called ‘what-you-see-is-all-there-is’ bias, meaning that they are quite confident about their estimates because they are unaware of certain critical details of the project or the environment in which the project is undertaken.

- Telehealth is here to stay as patients phone their GPs in droves

- Breakdancing for equality – and now a spot at the Olympics

“Providing feedback to planners upon the completion of the project is vital for their learning and information updating so they can provide a better estimate next time. Interestingly, providing information about every single detail of the project, no matter how minuscule, does not always help as it can overburden and distract the planners.”

Dr Matej Lorko recently completed his PhD at the Macquarie Business School and is now an Assistant Professor at the University of Economics in Bratislava, Slovakia.

Professor Maroš Servátka is the Director of the Macquarie Business School Experimental Economics Laboratory.

Dr Le Zhang is a Senior Lecturer with the Department of Economics at the Macquarie Business School.