The Social Dilemma, the recent Netflix documentary-drama, did not teach me anything new about how Facebook (mis)handles our data; I knew it already.

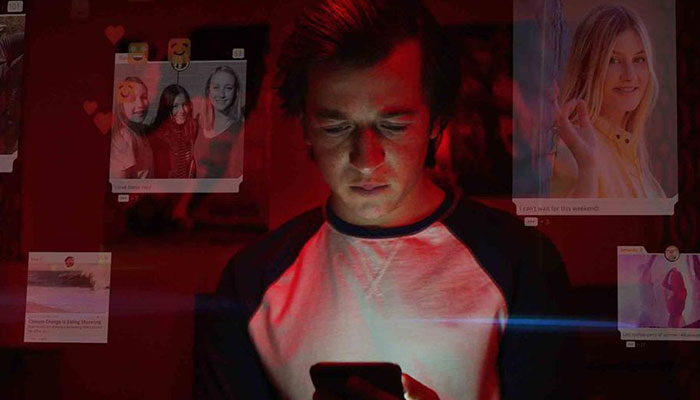

Human impact: Skyler Gisondo as Ben in Netflix's alarming documentary-drama about social media, The Social Dilemma. Photo credit: Netflix

But it made me, as a lawyer, think: is there really nothing we can do about this? Do we have laws that protect us from use and misuse of our data?

Bad news: we do not own our data

We have property rights over our house (if we own it), closet items, photos we take and upload online, and even our emails and tweets.

But we do not have any property rights over our data – information on what sites we visited, which posts we liked, what we bought online.

We easily agree on whatever ‘terms of service’ they propose. We do not have a choice: either accept or not use their services.

Why does it matter? We can (at least under law) prevent others from copying and sharing all content that we own or require payment if somebody wants to use it.

However, we can’t require payments for the use of our data, or entirely stop others from using it, because we do not own it.

Not everything is lost

The good news is that we can to some extent control who and how our personal data is used. So-called ‘privacy laws’ require that Facebook and other digital platforms get consent from us before they access and use our data, and sell it to other third parties.

Data deal: Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg ... the business model allows Facebook to claim that is it not selling our data, says Dr Matulionyte.

The problem is that it is too easy for them to get our consent – we easily agree on whatever ‘terms of service’ they propose. We do not have a choice: either accept or not use their services.

The other problem is that we often do not read, and even if we do, we do not understand the practical consequences of our consent. Here is a sentence from Facebook privacy policy:

“We collect the content, communications and other information you provide when you use our Products, including when you sign up for an account, create or share content, and message or communicate with others.”

The truth is that currently Facebook is not free – we pay for it by giving access to our data.

When you read and accept this, do you realise that your single 'like' for a furniture shop on Instagram might mean that you will be bombarded with ads from different furniture shops on Facebook, your email account and other websites you visit for the next few weeks? This is the result of your consent.

Another problem is that privacy laws protect only ‘personal data’, that is, data which may disclose the identity of the person, such as email addresses, birth date and images.

Facebook does not need to sell personal data to businesses. It just asks businesses what sort of audience (based on sex, age, ethnicity, education, etc) they want to target in their advertising campaigns, and disseminates advertisings among these audiences, for a fee.

While generating huge profits from this, the business model allows Facebook to claim that it is NOT selling our personal data.

Is the situation better overseas?

We sometimes hear that in other countries, and especially in Europe, consumers are better protected.

This is true, Europeans have many more rights online. For instance, they should be clearly informed who exactly will collect their information, with whom data will be shared, and they can withdraw consent and require deletion of all personal data at any time.

While all of this sounds great, removal of consent would normally mean that the user will not be able to use the service anymore. So, the main problem is not really solved yet, even in Europe.

Where next?

Australian privacy and data protection laws can and should be improved, for instance, by introducing protections that are already available in Europe.

- Fruit fly breakthrough puts killer mozzies on notice

- Please explain: why is NASA returning to the moon?

Consumers around the world still need to fight for the possibility to deny consent to use our personal data and at the same time keep the possibility to use Facebook and other digital services.

The truth is that currently Facebook is not free – we pay for it by giving access to our data. If we don’t want to share data, either Facebook will have to find a different business model, or we will have to pay cash for it.

Dr Rita Matulionyte of Macquarie Law School is an international expert in intellectual property and information technology law.