Tucked at the end of a street in the sprawling grounds of Macquarie University, in a low-set brick building wrapped around a courtyard with leafy playgrounds at the back, something of a miracle happened for the Diamond family from Sydney’s North Shore.

Happy days: At MUSEC, Jayden, 7, found a learning environment where his literacy - and emotional well being - improved enormously, says mother Kerry (pictured centre) with teacher Dr Sara Mills, (pictured right).

There, after just a week early in 2020, then six-year-old Jayden Diamond’s very difficult behaviour made a dramatic U-turn. And over the ensuing year, his literacy climbed from the bottom 1 per cent to a level appropriate for his age.

“His progress was just phenomenal,” says his mum Kerry Diamond. “At the beginning he could maybe sound out 10 letters; now we read chapter books at home, so that’s incredible.

“And there was a big change at home generally – he doesn’t fight and resist everything like he used to, including going to school which was a battle every single morning. I put it down to the fact that he is so happy at school; he doesn’t feel the need to try and control everything else around him.”

Jayden, who has high-functioning autism and is now seven, is enrolled at MUSEC, the on-campus Macquarie University Special Education Centre for children with special learning needs.

It was like for the first time in his life, he was happy to be left at school. It was a very, very quick change in him.

For more than 25 years, MUSEC’s specialist teachers have used principles and methods based on the latest research findings to teach children with disabilities including autism, mild or moderate intellectual disability, and reading disability. As well as a laser focus on literacy and numeracy, a school week for pupils incudes art, sport, songs, dance and play.

Some children will transition into mainstream schools in the later years of primary or before – it all depends on the individual child – while others will go on to special needs high schools.

“We have an amazing team of teachers, who are so dedicated and so skilled, it is a wonderful environment,” says school principal Dr Sally Howell.

“We use a consistent evidence-based approach, with the children also knowing very clearly what is expected of them and following through.

“Effective instruction comes back to the basics – you have to assess very carefully where the child is at; you make the steps small enough to guarantee that they are going to enjoy success; and you give really explicit instructions.”

Falling through the cracks

While Jayden Diamond’s years at day care and pre-school had been happy ones, once he started kindergarten at a private school it fast became clear that he had issues with learning to read. At least, it was evident to his parents, says mum Kerry; the school itself failed to take proper note.

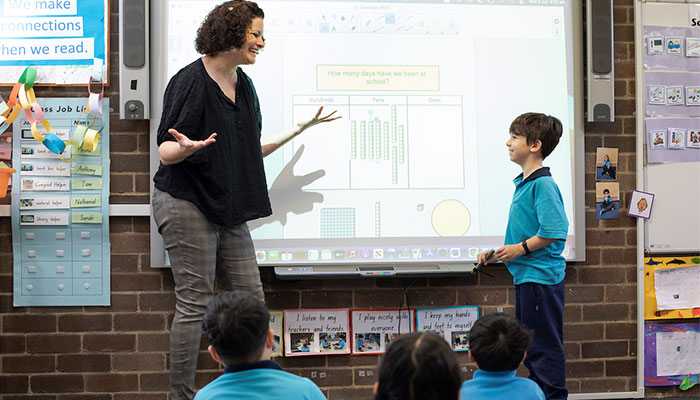

In a class of its own: MUSEC methods are evidence-based which dictate that learning steps are small enough to guarantee that children enjoy success, says school principal Dr Sally Howell.

“Unfortunately, he wasn’t receiving recognition for the issues that he had, or the right kind of support, and his behaviours spiralled downwards. He became ‘the naughty kid’ – they weren’t looking at it deeper than that – who was punished for bad behaviour,” says Kerry.

“And there were major issues with separating in the morning … dropping him off became a nightmare.”

For Kerry, it was blatantly obvious that the behaviour was a result of Jayden not coping with what was happening in the school environment, which she was having to spell out to the teachers.

“I shared the fact he had autism very openly with the school, and I was putting up my hand and saying, I am pretty sure he’s dyslexic, and when I had him assessed outside of the school, he scored in the bottom 1 per cent for his literacy – and yet literacy was never flagged to me as something that I needed to address outside of the school. I was continuously told that he was capable and they would just try and push him.”

In order to keep him regulated in class, teachers would give him food during lessons, a strategy that concerned his parents: “I just thought, what is this teaching my child about regulating yourself, that you should eat to stay calm?,” says Kerry.

“He was never removed for separate lessons, he was always in the whole class environment, so it was this constant feeling for him that he couldn’t do what the other kids could do and that he was dumb.”

When the children are in the classroom they are constantly being praised for the behaviours that we want to see and we ignore trivial misbehaviour.

At home, he was oppositional – “everything was a fight; leaving to go to school was a fight every single morning, it was very, very difficult behaviour.”

Jayden went back to the same private school in Year 1, but his dread and its accompanying behaviour came back in full force.

“Straight away I just knew this wasn’t good for my kid. I made the decision that I just didn’t want him to continue,” Kerry says.

“He was in such a bad way after I removed him, then we had a one-week trial at another school which was a total disaster, and then a literacy specialist gave me MUSEC’s details.

“He just couldn’t have been put into a mainstream setting because his walls were up, he was angry, he was acting out. No one would have been able to cope with him except a team like this here.”

Following the rules

As soon as Kerry looked through the observation window of a MUSEC classroom and saw kids working at desks, just like a regular school, she instantly knew it was exactly what Jayden needed.

The right stuff: Jayden's mother Kerry says she saw positive changes in her son very quickly after enrolling at MUSEC, which is located in the grounds of Macquarie University, pictured above.

And so, Jayden’s first days at MUSEC went something like this: the separating from his dad in the morning was the familiar nightmare. Through the day, he was angry and swearing at the teachers and didn’t want to be a part of the class, determined to just hold on to his fidget toy.

When Jayden swore, the teachers would carry on as though nothing had happened.

But, in line with the school’s ‘positive behaviour’ approach, teachers set explicit expectations for Jayden.

“When the children are in the classroom they are constantly being praised for the behaviours that we want to see and we ignore trivial misbehaviour – in our setting using swear words would be deemed trivial behaviour,” says Howell.

Says Kerry: “He just very quickly realised that he couldn’t push the boundaries, that he had to follow the rules. He certainly wasn’t needing to eat during lessons, and within a week he stopped needing his fidget toy in his pocket.

“I think by week two, the drop-offs were smooth. It was like for the first time in his life, he was happy to be left at school. It was a very, very quick change in him.”

Looking to the future

Now in his second school year at MUSEC, Jayden will ultimately move back into mainstream schooling, when he is ready. It is what his parents and MUSEC want for him because “without a doubt” he is capable of achieving well in a mainstream environment.

“Although he has caught up academically and is doing so well here emotionally and in terms of friendships and all of that, I want to give him time to mature a bit more – and buy me extra time to do the research to find the right school that will support him,” says Kerry.

“We just feel blessed to have found MUSEC, because it has done wonders for him.”

Macquarie University Special Education Centre (MUSEC) is a research-based special school for children from Kindergarten to Year 6 with disability including mild or moderate intellectual disability, autism or language disability.