Boutique owner Amy never thought she’d be grateful to be able to hide behind a mask.

While on holiday in Bali about five years ago, she and her identical twin sister had fillers injected to plump out the lines in their upper lips. It wasn’t the first time they had had minor cosmetic procedures at the clinic, and they thought it was safe.

Both assumed the fillers had dissolved after a few months, as they had been promised.

The first indication Amy had there might be a problem came after she slipped while opening a heavy fire door about 18 months ago, hitting herself in the face.

“It was very painful at the time, but it stopped hurting after a while and I didn’t think any more of it,” the now 64-year-old says.

“A month or two later, a blue-purple colour began to spread across the top of my lip, and there was a hard spot under the skin where I’d hit it.”

Dr Hussain has drained it twice, but it keeps coming back and he thinks some of it has calcified.

When the discolouration and lump didn’t go away, she went to her GP, who took a biopsy. The results showed no cancer, but the biopsy incision kept weeping and refused to heal – and then the lumpiness began to spread along her lip.

She was referred to Macquarie University Hospital Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, Associate Professor Gazi Hussain, who administered injections to dissolve the lumps in preparation for plastic surgery to repair the scarring.

But just before Christmas, the situation deteriorated further. Amy's lip swelled dramatically, and she needed an emergency procedure to relieve the pressure.

“It felt like it was about to burst,” she says. “All this gunk had built up. Dr Hussain has drained it twice, but it keeps coming back and he thinks some of it has calcified.

Horror story: Following a procedure in Bali five years ago, Amy will need plastic surgery to fix the scarring across the top of her lip, but only once everything has healed.

“There’s a sort of tunnel under the skin leading up to my nose, and I’ve been left with a hole on one side of my lip and a scar on the other. One side of my mouth has been pulled up.

“I can’t have plastic surgery to repair this until everything has healed properly.”

With such a public-facing job, the scarring has shaken Amy's confidence, and left her glad that masks are still so common.

Being a twin has made it even harder for her to deal with.

“I work and socialise with my sister, so it’s a constant reminder of what I should look like,” she says.

“You hear the horror stories about breast implants and calcification, but I never thought something like this would happen with fillers.

“I just have to live with it now, but I keep hoping for a better result.”

The rules surrounding cosmetic procedures

In Australia, the products and drugs used in cosmetic surgery are strictly controlled, but that isn’t always the case overseas.

“When we see instances of fillers that are lasting for years instead of months, as they have in Amy's case, it has to raise questions about what was really injected,” Hussain says.

“Here, you would receive an approved synthetic version of hyaluronic acid (HA), which the body both produces and breaks down naturally, and which can be dissolved with a counteracting injection of hyaluronidase if necessary.

“Overseas, those safeguards aren’t in place, and you could be receiving a contaminated product or something else altogether.

“In cases like this, reversing the effects becomes problematic. You can’t just remove it and have everything return to normal.”

However, while the products are controlled in Australia, there is no requirement for the people administering them to be trained.

Choose carefully: The best way to reduce risks is to only see accredited plastic surgeons.

At some clinics, a nurse gives the injections, but at others it could be someone with no medical qualifications or even a basic knowledge of anatomy.

With some parts of the beauty industry, both locally and abroad, trying to trivialise minor enhancements, we are in danger of forgetting they are still medical procedures that carry a certain level of risk, Hussain says.

“The person giving your injections may have attended a demonstration night, or just watched a video,” Hussain says.

“We hear about Botox parties, where there’s alcohol served and a ‘practitioner’ goes around giving injections, or people getting lip fillers done during their lunch hour.

It’s awful for the patient, but the only way to deal with necrotic skin is to cut it away and try to reconstruct the area.

“Some of the people offering this service are working from their living rooms and ordering the products online.

“We’ve even seen influencers on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram telling their followers how to order the products and do their own injections.

“This is all being presented as being quite safe and normal – just as quick and easy as getting a wash and blow dry.

“But it’s nothing like getting your hair done.”

Reducing your risk

Most of the problems Hussain sees stem from poor technique, resulting in effects that eventually wear off, like lumpy lips, sagging eyelids or an unnatural, over-inflated look.

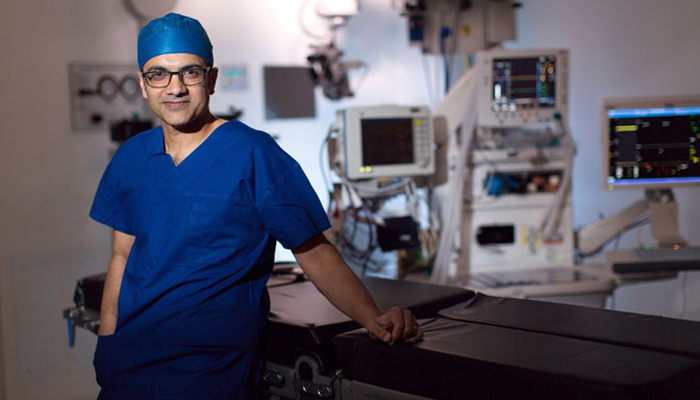

All in a name: Associate Professor Gazi Hussain warns there is officially no such thing as a 'cosmetic surgeon'.

In some cases, the results can be far worse.

“I’ve heard of two people in Sydney who have gone blind from having fillers injected into the tear trough under the eye, and there are other examples of this around the world,” he says.

“Another risk is intravascular injection – accidentally injecting filler into a vein or artery instead of under the skin. That can lead to necrosis, or skin death, in areas like the nose and the lips.

“It’s awful for the patient, but the only way to deal with necrotic skin is to cut it away and try to reconstruct the area.”

Beware the 'cosmetic' surgeon

With so many ‘cosmetic cowboys’ in the market, the best way to reduce the risks is to only see accredited specialist plastic surgeons, even for small procedures.

“People considering these procedures should beware of anyone calling themselves a ‘cosmetic surgeon’, as officially there is no such thing,” Hussain says.

“In my opinion, there should be regulations introduced so that only people with a formal surgical qualification from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons can perform these cosmetic procedures.

“We are medical professionals with a complete knowledge of anatomy, proper sterilisation equipment, and access to safe products, and we are prepared to deal with any emergency situation that might arise.

“Yes, the risks are low, but when things go wrong, they can go badly wrong.

“If you’re the person who has a problem, the effects can be devastating – and they’re not always reversible.”

Associate Professor Gazi Hussain practises at MQ Health Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Clinic.