When the now defunct Family Court came into existence in 1975, it was part of revolutionary reform that marked a new era of divorce law in Australia.

Hard yards: Prior to 1975, a spouse wanting to divorce in Australia needed to prove one of 13 fault grounds – or wait five years.

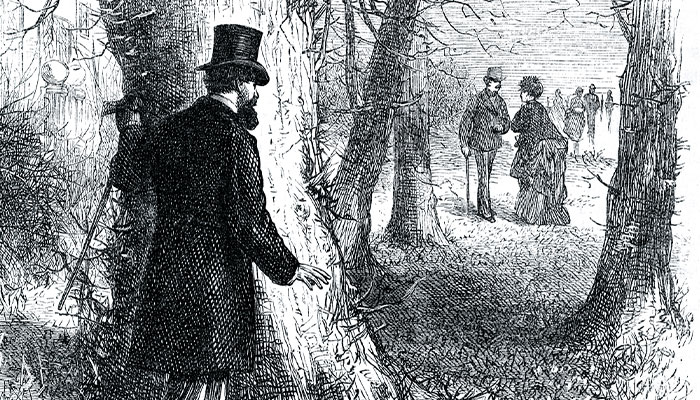

Gone was the need for a husband or wife to show fault on the part of their spouse, often requiring the services of a private investigator to gather the evidence – by bursting into hotel rooms with cameras, and the like.

Five years of separation was the only no-fault ground, but it was a long time to wait.

Adultery, insanity, imprisonment and habitual drunkenness were among the 13 fault grounds, one of which had to be proved in court before divorce would be granted.

A party would need to get a solicitor, a private investigator and if the matter was defended, you would need a barrister as well – so it was a very expensive process.

Hearings could be so salacious that 210 episodes of a show called Divorce Court screened on Australian daytime TV in the 1960s, with professional actors re-enacting actual divorce cases.

“Divorce was a rather vindictive process,” says Macquarie Law School’s Dr Henry Kha,

“Adultery would require a private investigator (PI), and it was also helpful to have one if you were applying on other grounds, such as desertion or cruelty, because they also required evidence.

“A party would need to get a solicitor, a PI and if the matter was defended, you would need a barrister as well – so it was a very expensive process.”

The sexist double standard

Under the Whitlam Labor Government, the Family Law Act 1975 introduced the Family Court and the principle of no-fault divorce. One year of separation became the only ground necessary to establish irretrievable breakdown of a marriage.

The Affair: An 1875 engraving shows a man snooping on his wife as she meets with her lover .... evidence was required to prove adultery, which kept private investigators busy.

Australia was decades ahead of the UK, which has taken until last year to implement no-fault divorce, and then only in England and Wales.

Up until 1975, however, divorce law in Australia closely followed the UK’s – and understanding UK divorce law is key to understanding Australia’s own evolution of this fraught, intensely human legal area, says Kha.

His book, A History of Divorce Law: Reform in England from the Victorian to the Interwar Years, charts the English journey from its introduction of civil divorce in 1857 – a fault system based solely on the ground of adultery with a sexist double standard at its heart that was transplanted to the Australian colonies.

“Prior to 1857 when the British Parliament passed the Matrimonial Causes Act, it was very difficult to get divorced in England,” Kha says.

- Please explain: Why does the world need poetry?

- Media at the crossroads: Why 2021 is a game changer for news in Australia

“It was a three-stage process that ultimately required a private Act of Parliament passed in the House of Lords.

“Between 1700 and 1857, there were three divorces on average a year, and only four women in all that time were successful in getting a divorce.”

After 1857, men could divorce their wives if they proved her adultery, but for the women it was much harder: in addition to adultery, they had to prove an aggravated enormity on the part of the husband such as desertion, cruelty, or committing incest or bigamy.

“That was the central double standard of the Act,” Kha says.

“Parliament at that time was all men who had a particular view of marriage and divorce – they reasoned that a man having affairs was more forgivable than a woman doing the same, because men were concerned about succession and having legitimate children.”

Colonies follow, then lead

Meanwhile, in Australia, the six colonies set up their own Matrimonial Causes acts and imported the additional fault grounds required for women to secure a divorce.

Tight knots: A 1930s wedding ... by that time in Australia, the sexist double standard had largely been expunged from divorce law, and many states would allow divorce on grounds besides adultery.

But whereas the English only removed the double standard in 1923, the colonies (except Victoria) each successively introduced legislation to expunge it from the late 19th century into the early 20th century.

By this time, says Kha, many of the states would also allow parties to divorce on grounds besides adultery – a move not taken by the UK until 1937, when it introduced cruelty, desertion or incurable insanity as further available grounds.

“The colonies were always a bit more progressive than the UK,” says Kha.

Ironically, in some cases the only thing a couple could agree on was the divorce itself, so they would team up – which was actually against the law.

“It was very difficult to justify the double standard even in the late 19th century, with the rise of women’s rights, particularly the right of married women to own property.”

Divorce law that relied exclusively on adultery was based on a conservative interpretation of Christianity – particularly Jesus Christ’s statement in the Bible that only sexual immorality should be a ground for divorce.

“This interpretation led to many unintended consequences – and also to a lot of collusion,” Kha says.

“Ironically, in some cases the only thing a couple could agree on was the divorce itself, so they would team up and typically the wife would say the husband had committed adultery, and he would agree – which was actually against the law because it was seen as a conspiracy against the court.”

One law, and lots of collusion

In Australia, as divorce rates climbed following World War II, the situation was "very messy" with each state still having its own legislation, says Kha.

“There were some really bizarre anomalies: for example, on one side of the Murray River, in Victoria, a party could divorce their spouse if they were insane, but on the other side of the river, in NSW, you could not.”

This changed when Federal Parliament passed the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1959, codifying 14 grounds for divorce that applied across the country.

“It was basically an amalgamation of all the different divorce laws that existed in each state,” Kha says.

- Solved – the site of Australia's first astronomical observatory

- World Hearing Day: Dementia link brings call for screening overhaul

“It wasn’t necessarily a more progressive law, just more procedurally simple.”

Kha imagines Australian couples mutually wanting divorce would have staged their own versions of the “Brighton Quickie”. This was a 1930s phenomenon in England whereby a couple would stage an adulterous scene at a Brighton hotel – typically involving the husband and another woman – with a PI on hand to capture the evidence.

“Collusion would have been a big factor in Australia as well. It was basically the same system – you can’t collude, that is a bar to divorce – but people did do it, because realistically how else would you get divorced under that system? And five years’ separation was otherwise a long time to wait.”

And then came Whitlam

By 1975, it was clear that the vindictive fault-based system was not really working, says Kha. Intent on instituting a simple system, the newly elected, social-reformist Whitlam government shepherded the Family Law Act through Parliament with largely bipartisan support. The main sticking point was the length of separation as some MPs pushed for two years.

Kha says that the 45-year-old divorce law has been “very successful” in terms of efficiency and access – it is cheaper than the days when only the middle and upper classes could afford divorce, and easy to understand with its sole ground of 12 months’ separation.

“The family law process is always going to be acrimonious, but it’s good that at least one area of family law has been simplified,” Kha says.

Dr Henry Kha (pictured) is Senior Lecturer in Law at Macquarie Law School. A History of Divorce Law: Reform in England from the Victorian to the Interwar Years is published by Routledge.