Does eating garlic protect you from the coronavirus? Can houseflies infect you with it? Does COVID-19 only affect the elderly? Based on newly published research, one in five adults accepts medical myths like these linked to the pandemic.

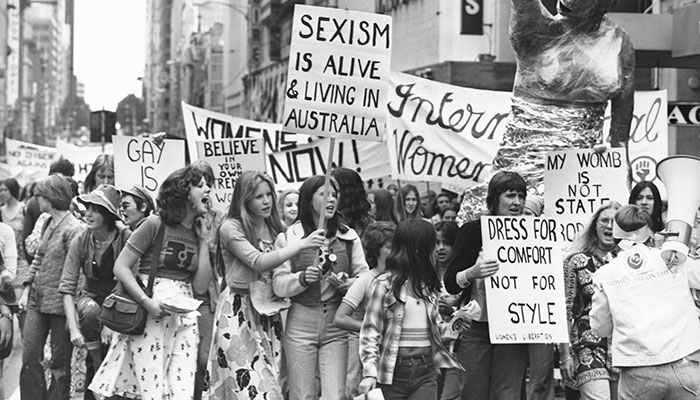

Believe it or not: Anti-mask protesters hit the streets ... researchers found people who demonstrate indifference to evidence are especially likely to accept misinformation.

In two separate studies, 1737 people aged between 18 and 74 were surveyed about their attitudes towards a variety of evidence-free claims circulating in the media and on the internet about ways to catch or prevent COVID-19.

The surveys (see them here and here) were conducted in the US in June 2020 during widespread lockdowns across multiple states, and tested attitudes towards conspiracy theories and misinformation including that 5G networks were spreading the virus or that coronavirus was a bioweapon.

The studies (see them here and here), conducted by a team of philosophy researchers from Macquarie University, the University of Hamburg in Germany and Groningen University in the Netherlands, found 20 per cent of adults thought they were immune to the coronavirus because of their age, their diet and a variety of other myths.

We need to focus on proving our experts are trustworthy because once people have lost trust it’s almost impossible to persuade them of anything.

“If 20 per cent of adults think they are immune because of their age, their diet, or their skill with a flyswatter, they may resist sensible behavioural choices such as social distancing, masking, handwashing, and being vaccinated,” says Dr Mark Alfano, an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Sydney’s Macquarie University.

“That in turn may lead them to infect both themselves and others – including others who are doing their best to stay informed and follow expert guidance.

- Budget spends big but needs a longer-term view

- Underwater drama as bossy stingray rules like a despot

“While it may be tempting to dismiss these ideas as misinformation endorsed by a minority of the population, the ongoing pandemic has shown that successful public health outcomes depend on everyone doing their part.

“When people refuse to wear masks even if other people are doing their part – you will still see the virus continue to spread.”

Researchers found people who demonstrate indifference to evidence are especially likely to accept misinformation.

Alfano says one in five people surveyed were happy to tell researchers that they don’t much care about the reasons for and against what they believe, and that once they’ve jumped to a conclusion they’re extremely reluctant to change their minds.

“If we did the same survey here in Australia I wouldn’t be surprised if the results were similar," Alfano says.

Defiant guests linked to wedding tragedy

A super-spreader event in Maine which occurred in August 2020 is instructive, Alfano says.

Notable failure: Then US President Donald Trump removes his mask after his hospitalisation for COVID-19 ... the US failed to ensure the independence of its public health experts, Dr Alfano says.

According to the Maine Centre for Disease Control, 62 guests attended an indoor wedding reception that violated the state’s 50-person cap on such events. Many of them contracted COVID-19, leading to an outbreak that infected at least 178 people, seven of whom are now dead.

However, none of those unlucky seven attended the wedding reception. They were all secondary or tertiary contacts of people at the super-spreader event. They died because members of their communities defied public health protocols.

If 20 per cent of adults think they are immune because of their age, their diet, or their skill with a flyswatter, they may resist sensible behavioural choices.

“Staying informed can be challenging. After all, tsetse flies transmit sleeping sickness, so it’s not irrational to suspect that houseflies could spread COVID-19,” Alfano says.

“Likewise, what you eat affects your health, so it’s reasonable to think that dietary choices might make someone less susceptible.

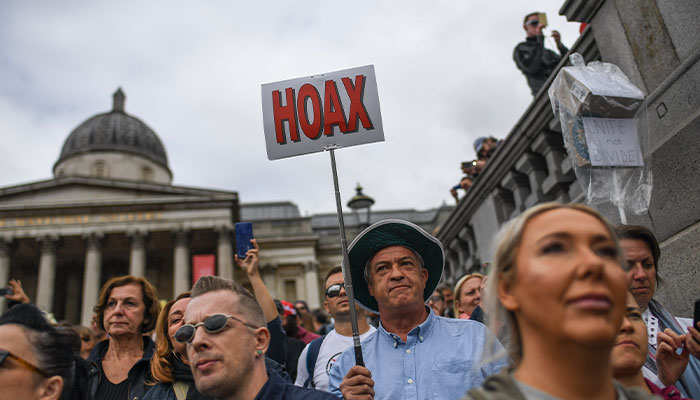

“In addition, however, there are people who think the pandemic has been greatly exaggerated, that it was a hoax devised to harm former US President Trump’s re-election chances or to increase the power and profits of the pharmaceutical industry.”

Trustworthy sources crucial

Alfano says the research shows containing the spread of COVID-19 can in part be positively influenced by where people place their trust.

Mass trauma: A COVID-19 field hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil ... the more people who flout expert guidelines, the longer it will take to put the pandemic behind us, says Dr Alfano.

“We don’t want to tell people what to believe. We make no claim to medical expertise. But we are experts on trust and trustworthiness, and we want to urge people to place their trust wisely,” Alfano says.

“Partly because not everyone is equally well-informed about the pandemic, most countries have been unable to control it. The more people who flout expert medical guidelines, the longer it will take to put COVID-19 in the rearview mirror.”

When investigating why the adults surveyed accepted misinformation about COVID-19, the researchers found credence in medical misinformation primarily depended on how people deal with new evidence.

We found that people who do not fall for COVID-19 misinformation have two qualities in common: they are curious, and they do not cling to their views.

Participants were asked whether they liked to learn new things, whether they thought it was important to know why things happen, whether they preferred to hear both sides of a debate, whether they were aware that they don’t already know everything about certain issues, and whether they therefore relied on experts such as doctors.

“We found that people who do not fall for COVID-19 misinformation have two qualities in common: they are curious, and they do not cling to their views,” Alfano says.

“Instead, they keep an open mind and change their views when they encounter evidence from trustworthy sources that contradicts what they previously believed.

“A much larger group of people are curious, but they are not particularly interested in ascertaining the trustworthiness of their sources. And that’s where the danger lies, because it is precisely people with this profile who tend to believe COVID-19 myths. Their curiosity leads them to collect lots of information about the pandemic, but they neglect to ask which sources they should trust.”

Experts must demonstrate independence

There is a lesson here for policymakers, the researchers warn. Public health experts must demonstrate trustworthiness, with our medical institutions also taking steps to ensure they are seen as independent and shielded from political influence.

Some governments have done a better job of ensuring such independence than others, says Alfano, with notable failures in the United States and the United Kingdom, among others.

- Teens reap benefits of good connections with teachers

- The power of quotas and why Australia needs them

If even the most curious and open-minded citizens have reason to distrust the experts, the ongoing pandemic may continue to rage indefinitely as artificial herd immunity remains out of reach.

“We need to focus on proving our experts are trustworthy because once people have lost trust it’s almost impossible to persuade them of anything,” Alfano says.

Dr Mark Alfano (pictured) is Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Macquarie University.