Australia's environment ministers are currently discussing measures to eliminate the domestic trade in elephant ivory and rhinoceros horn, after becoming the latest jurisdiction to commit to nationwide trade bans.

Future fate?: Iman, the last known Sumatran rhinoceros in Malaysia, died on Saturday leaving the species officially extinct in the country: Facebook/Borneo Rhino Alliance.

It comes as ministers prepare for a highly anticipated review of Australia’s environmental law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, with campaigners calling for stronger legislation to save endangered species.

This commitment brings Australia one step closer to enacting domestic trade bans, as recommended by last year’s Parliamentary Joint Committee on Law Enforcement Inquiry. In its final report, the committee referred to similar measures already being carried out overseas, most notably in the UK.

In the lead up the meeting, eyes were trained on London where the High Court ruled against a small group of antique dealers who had sought to overturn the UK’s Ivory Act just days before. New Zealand is also currently exploring options for limiting trade within its borders.

The trade in elephant ivory and rhino horn is part of the global illegal wildlife trade, worth an estimated US$7 to US$23 billion per year, according to a Parliamentary Joint Committee report into the domestic ivory trade released in September 2018.

As well as changes to legislation, new technology is also being developed in a bid to combat the illegal ivory trade.

Most rhino horns currently in circulation are already fake - upwards of 90% by some estimates.

Earlier this month, scientists from the University of Oxford and Fudan University published a report on a new method they've invented to create fake rhino horn using horse hair. This method involves bundling horse tail hairs and adhering them together with silk-based fillers. This isn’t the first time researchers have attempted to create fabricated rhino horns, with biotech firm Pembient anticipating a 2022 release for its genetically identical 3D-printed horns.

The common intent behind developing these techniques is to potentially stop poaching by flooding the market with fakes to drive the street value for rhino horn down, making the enterprise less profitable for organised crime - or so the theory goes.

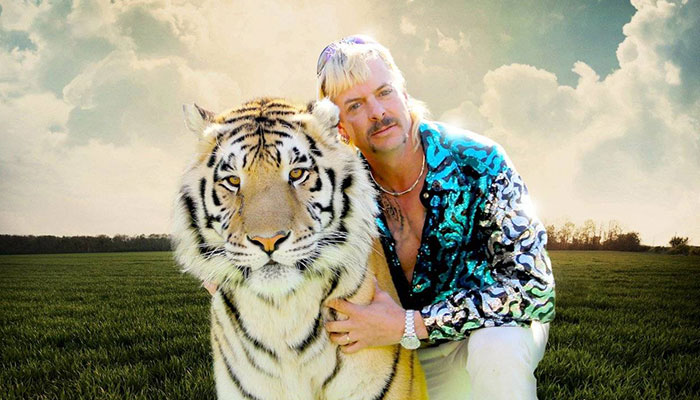

High price to pay: Demand for ivory and horn has decimated populations of elephants and rhinos in Africa and Asia.

While creating synthetic substitutes is an established tool in conservation, some organisations including the International Rhino Foundation and Save the Rhino International have been critical of these sorts of projects, with the latter referring to this latest attempt as ‘ill-conceived’. But why?

- World-first findings pinpoint where and when sharks are more likely to attack

- Insect hotels and why you should build one

- Solving the problem of honey bee colony collapse

Firstly, syndicates continue to fund poaching even though criminal penalties and prosecution rates have increased; and most rhino horns currently in circulation are already fake - upwards of 90% by some estimates. Fakes are usually carved out of wood or the horns of other species including buffalo.

Secondly, these efforts are often based on a flawed understanding of the market, oversimplifying the motivations and behaviours of rhino horn buyers as well as the range of known uses. Because a large component of the market desires rhino horn to cement their perceived status and affluence (for example, those purchasing the horn as ‘elite gift-givers’, ‘social users’, and ‘investors’) it is unlikely that these buyers would opt for cheaper goods, preferring instead to pay a premium for the real thing.

Rhino research: Bending says public pressure must help to end the ivory trade in Australia.

Driving the price down may then only make the commodity more accessible to those who may not have considered purchasing it previously, exacerbating rather than mitigating the problem. I often use markets for fake cosmetics and clothing as examples to illustrate this scenario. High-end fashion labels like Gucci, Chanel and Prada can charge their clientele handsomely for genuine pieces whereas the masses seeking to emulate that lifestyle on a budget can buy knock-offs purchased from physical and online markets.

Thirdly, as Dr Richard Thomas, from the wildlife trade monitoring network Traffic, says “[p]ushing a synthetic alternative could help to reinforce the perception that rhino horn is a desirable commodity, thus perpetuating existing demand". There are also complex legal and ethical questions around intellectual property and ‘biopiracy'.

As the saying goes, ‘nobody needs rhino horn but a rhino’ and it is more likely that demand-reduction through education and other behaviour change measures coupled with strengthening anti-poaching efforts and strengthening legal frameworks will secure the future for our precious pachyderms for generations to come. The sooner Australia closes its domestic trade, the better.

- Zara Bending is a doctoral researcher and academic at the Macquarie Law School, Associate of the Centre for Environmental Law, and Board Director of the Jane Goodall Institute Australia.